Arts & Entertainment

Larry Wells' Days of Wine and Letters

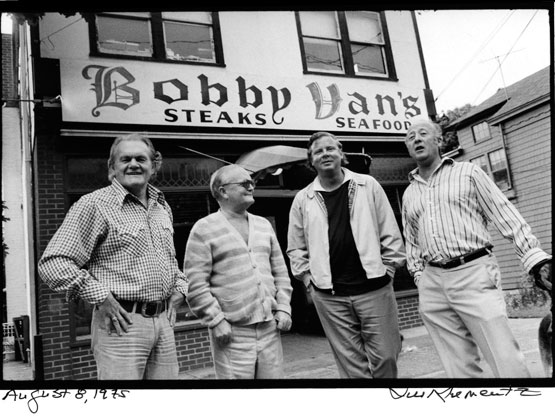

From left, writers James Jones, Truman Capote, Willie Morris and John Knowles stand in front of Bobby Van’s Restaurant in 1975. Photo by Jill Krementz

By Larry Wells

“People will come, Ray…for reasons they can’t even fathom. They’ll turn up in your driveway not knowing for sure why they’re doing it. They’ll arrive at your door as innocent as children, longing for the past.” – Field of Dreams

In 1980 author and magazine editor Willie Morris left Bridgehampton, N.Y., where he had lived for a decade after leaving Harper’s, and moved to Oxford. He often spoke of Bobby Van’s, his favorite Long Island hangout. Earlier I had visited Morris in Bridgehampton, and at 3 a.m. we closed down Bobby Van’s. This was Willie’s boot-camp for writers. He had written a New York Times op-ed piece about Bobby Van’s as a watering hole for the likes of Truman Capote, James Jones, George Plimpton, Irwin Shaw, and John Knowles. An overnight tourist migration turned quiet, unpretentious Bridgehampton into a glitzy seasonal resort. Similarly, Morris’ widely-circulated stories about Oxford helped create a resort-and-retirement boom here in the 1990s. Oxford and Bridgehampton thus share the dubious distinction of having been reshaped by Willie Morris’ imagination. With my wife, Dean, I returned to Bobby Van’s in 2002 and discovered that it, too, had changed with the times.

Lunch conversation at Bobby Van’s is lively and loud, interrupted periodically by the ringing of cellular phones or beepers. People at nearby tables stop talking as if the call might be for them, the momentary silence punctuated by the clink of heavy cutlery against real china. Our group is seated at what used to be the “writers’ table” next to the front window at this legendary literary watering hole in Bridgehampton, N.Y., a small, hospitable town on the east end of Long Island.

At our table are Gloria Jones, wife of author James Jones and a regular at Bobby Van’s, and Marina Van, former wife and business partner of the restaurant’s founder, the Bobby Van, whom we are expecting to join us at any minute.

While adjacent diners talk of interest rates and tax-free bonds, we discuss the lamentable lack of Oscars for The Thin Red Line, based on the James Jones novel. Gloria is looking forward however, to selling movie rights to Whistle, the last novel of the trilogy that began with From Here To Eternity.

“It used to be there were no fur coats at Bobby Van’s,” Marina observes. “Now, look around. You see black mink, brown mink, grey mink. In the old days, the only one wearing a fur coat was Tiny Tim.”

The old days were the 1970s, when Bobby Van’s was a home-away-from-Manhattan for a dozen major writers and their families, friends and companions. The old Bobby Van’s was darker, gloomier, filled with words and booze, writers happily arguing, debating, gesturing with their cigarettes, drinking, taking up causes, while Bobby played cool jazz on his piano. “Writers wanted more from a bar than a shot and a beer,” Marina says thoughtfully. “They wanted style and class. Bobby Van’s offered them that.”

Marina remembers a night when she was getting undressed to go to bed. She and Bobby lived upstairs over the bar. She heard Bob Dylan singing. “Bobby comes to the bedroom,” she recalls, “and I said, ‘You finally broke down and put Dylan on the jukebox.’ He said, ‘No, it’s really Dylan. He’s downstairs playing the piano. Get dressed.'”

It was not unusual for Dylan to show up with a harmonica in his pocket. On one spectacular night, John Lennon arrived with Dylan. Bobby was playing the piano and the famous duo played their harmonicas along with him.

The new Bobby Van’s has ceiling fans, soft lighting, a sunny and warm ambience that says welcome. Bloody Marys are rich and spicy. The signature dish is a 24-oz porterhouse steak for two, smeared with butter and seared crusty-brown in a 700 degree oven. But the literati have been replaced by the glitterati.

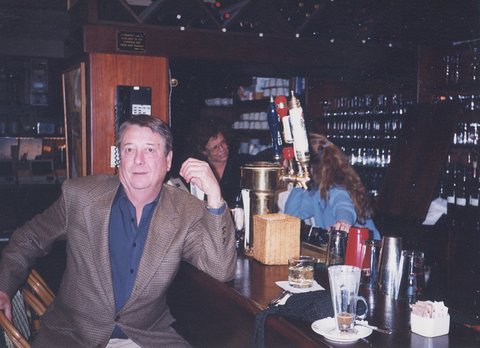

Enjoying a meal at Bobby Van’s are Larry Wells, far left, his wife Dean Faulkner Wells, far right, and Bobby and his ex wife Marina.

Owner Joe Phair, who bought the restaurant five years ago and since has opened a second Bobby Van’s in Manhattan, amiably ticks off a list of regular customers of reknown: “Lenny Reggio, owner of Barnes and Noble, lunches here. Alec Baldwin owns a house in Amagansett; he and his wife, Kim Basinger, are in here. Susan Lucci [star of ‘All My Children’] comes in for brunch sometimes. The soap opera stars usually have brunch late on Saturdays. Peter Jennings is also here on the weekends. We see a lot of TV people, on Saturdays mainly, at lunch. Between the fourth of July and Labor Day the population booms from 20,000 to 300,000. Every bed must have two bodies in it. You see all these characters by the dozen and tourists hunting celebrities, saying Who is that! but the celebs like it here year-round because nobody bothers them.”

Gloria and her friends Elaine Steinbeck, Shana Alexander and Tee Max⎯Mrs. Charles Addams⎯regularly share a table affectionately known as the “widows’ table,” set apart from the others in the bar next to the grand piano and offering, no doubt, the most interesting table talk on Long Island.

Over the bar counter, framed photos of writers attest to Bobby Van’s heyday as a literary Camelot. I step into the bar area to look at a famous foursome: James Jones, Truman Capote, Willie Morris and John Knowles, looking young and confident and a bit self-conscious at having their picture taken. Suddenly Bobby Van appears at my elbow and we exchange warm greetings. It’s been 20 years since I saw him here.

“It just happened one day,” he says about the historic bar photo. “The writers seemed amused that anyone would want to take their picture. They came out in front of the place and stood around laughing while Jill Crementz, the photographer, lay down in the street to get the sign over the building in the picture with them. I stopped traffic so she could get the shot.”

Now a fulltime professional pianist, Bobby Van is dapper and fit at fifty-four with an artist’s sensitive face, quick to laugh or to frown. A Long Island native, he was born into the arts. His great-great-aunt was the second wife of poet Walt Whitman. Admitted to Julliard at age 15 he attended music school on weekends while he was still in high school. Vietnam interrupted and subsequently derailed his formal musical training. After the war he went looking for a place to jumpstart his career. He chose the East End. It was not long before he had a successful restaurant.

“We opened in May of ‘69 and by ‘72 had a good business,” he says, looking up at the photo. “New York had not discovered this place yet. This place [Bobby Van’s] was like a living room where everyone was welcome. I’d play the piano and the writers could relax. It was a salon⎯if you’d like to call it that. There was never any hype about the writers who hung out here. Then Willie Morris wrote an op-ed piece for the N.Y. Times [March 1973]. The next day it was pandemonium. People were pushing to get inside the place. We had to lock the doors during regular hours. People were wild to get in and it wasn’t for the bluefish.” My friend and college classmate Winston Groom, author of Forrest Gump, told me, earlier, what he remembered most about Bobby Van’s. Having moved to Bridgehampton in 1975 as a young journalist and reporter, he was writing his first novel, Better Times Than These, a war story based on his Vietnam experiences.

“I remember when beer was seventy-five cents and a hamburger a dollar and a quarter at Bobby Van’s,” Groom said. “The first place was across the street from its present location. It had a big room with a long bar in the front and a smaller dining room in the back. The first time I went in there, the local writers were sitting at a table in the back. At the table were Irwin Shaw, Jim Jones, Willie Morris, John Knowles and Truman Capote. They did not put on airs. It was a very relaxed atmosphere, very easy going. For a young writer to go in there and be invited to join them was kinda like dying and going to heaven.” “Beer was only seventy-five cents?” Bobby says with a straight face. “Winston must be mistaken.”

Van sits at the old grand piano next to the front window, settles himself on the polished bench, lays his fingers on the keys and quietly frames a chord or two.

“Until Willie’s article,” he recalls, “people had mainly looked at the Hamptons as a seasonal place, a resort area; but not realizing that there was life here year round, creative people they could get along with. That was what attracted the writers. And so the perception changed. Big names were in here all the time, Mayor John Lindsey and his wife Mary were living out here. Julie Andrews and Alan Alda were regulars. There was a great mix of people, not clique-ish, and the so-called elite respected it. One summer the movie agent Swifty Lazaar wanted to rent Bobby Van’s on July 4th. Offered me $10,000 for a few hours. I told him ‘No, I can’t do that to my regular customers.'”

We go outside for a smoke. It’s a grey day, intermittent squalls blowing in off the beach, gulls flying over Main Street. We huddle under the Irish-green awning of Bobby Van’s. A handwritten sign on an adjacent children’s shop reads, “Back in Five Minutes.” Even now, in off-season, a constant stream of cars goes by. Bridgehampton, Southampton, East Hampton and Sag Harbor are the jewels in the East End crown, treelined streets of shingle-sided cottages cheek by jowl with fin de siecle vacation homes of the rich and famous (or just plain rich).

Bobby explains how the area was settled. Polish and Irish immigrants moved here before the Revolutionary War. By the 1800s they were supplying New York City with vegetables and produce. For several decades it was a sleepy agrarian corner of the peninsula, almost a separate state, hard to get to and inhabited mostly by farmers. Then eastern Long Island was discovered at the turn of the century by industrialist Henry Ford II and first families of Philadelphia such as the Wanamakers and Biddles, who built Victorian summer palaces. During the Roaring Twenties, the Hamptons took on a boozy reputation of high rollers and wild parties. Jay Gatsby had arrived.

“In the ‘60s when I first moved out here,” Bobby observes, “we were all running away from something. I had come back from Vietnam and was starting my life over. Willie Morris had left Harper’s. Jim Jones was looking for a home in the country, for privacy. In a sense we all had something in common. Peter Matthiessen was already out here, I think. Or was George Plimpton the first?” To answer the question, I phone Plimpton at his Paris Review office in New York. He is his usual, affable self and, like most writers, candid to a fault. “Well, the artists were the first ones to be attracted out there,” he observes, “drawn by the so-called golden haze over the potato fields. Maybe the haze was just the booze⎯god knows⎯but there were a lot of artists out there. Then along came the writers. Peter Matthiessen was the fellow who drew me out there. There’s a road that at one time had more writers and artists per square foot living on it than any road in the country. It runs between Route 27 and the sea. It’s called Sag Main Road and on that road lived, at one point, Matthiessen, Charles Addams, the cartoonist, Jim and Gloria Jones⎯and coming down the street⎯Kurt Vonnegut is on that road, Truman Capote had a house just off that road, John Irving is just off it, Linda Frankie is on the road. Caroline Schlossberg⎯Caroline Kennedy⎯she lives on that road. Uh,”⎯he pauses and I sense him smiling at the other end of the line. ”I lived on that road. I’ll throw myself in there.”

Plimpton doesn’t live on that road anymore. He returns every August, however, to host a charity fireworks show at Boys Harbor, a children’s summer camp which benefits from the proceeds. Although writers and artists still congregate in the area, they have been replaced, in the public view at least, by stars of film and stage. So much so that the East End has become known as “Hollywood East.” Steven Speilberg and Kate Capshaw have a summer residence in the Hamptons as do Kathleen Turner, Chevy Chase, Saturday Night Live’s Lorne Michaels, and singers Billy Joel and Jimmy Buffett. Every summer, streets are jammed with tourists hoping to spot a celebrity or two on the way to the beach.

Actor Roy Scheider lives in nearby Sag Harbor and often enjoys breakfast at the Candy Kitchen Cafe in Bridgehampton, a few doors down from Bobby Van’s. For most of the year, movie stars are treated here like locals until the tourist hordes arrive in the summer to try to find and photograph them.

Scheider dresses as most of the locals in jeans and sneakers. At first glance one thinks irresistibly of the police chief protecting “Amityville” in the movie Jaws. Even with senior citizenhood on the horizon, face weathered and wrinkled, Scheider looks ready to take to the beaches if a Great White were spotted cruising the Hamptons.

After lunch, Marina and Bobby take me for a tour of the flat lush farmland where new homes are being built at what is, for some, an alarming rate. The rich “Hampton loam” that created farming fortunes a century ago has become too valuable to farm. The two-story frame houses of early Irish and Polish farmers still dominate the country roads; but subdivisions are encroaching on what used to be open fields. The descendants of the original families have found another use for the land and potato fields are shrinking.

Restored windmills are prominent landmarks in every township, a symbol of the past. Cemeteries permeate the landscape, tombstones standing unexpectedly behind a one-room schoolhouse or a pond in the center of town, as though to remind tourists the Hamptons are a historic community. Sag Main Street respectfully splits into two lanes around a graveyard where James Jones’ ashes are buried. We walk through the cemetery looking for the marker. Birds sing in the bare branches. The rain has stopped and the air smells sweet and salty.

We can’t find Jones’ gravestone. Marina calls Gloria on her cell-phone. Standing in the wet grass, spring just around the corner, at home in a cemetery where writers have been laid to rest, Bobby Van reminisces about the days of wine and letters: “We put writers’ manuscripts on the Jitney [bus] to send to their editors. The writers trusted us to do it. Most of the time our customers were from the publishing business, but later television personalities moved out. Peter Jennings, Roone Arledge, Howard Cosell, Jack Whitaker, Mark Goodwin [of TV’s Goodwin and Todman]. By 1976 New York wanted a piece of the Hamptons. They started writing books about the Hamptons. Barbara Howar’s Laughing All the Way was one of those books. It was a great camaraderie while it lasted. We made money in the business, but that was not the consensus. It was the beauty and grace of the land, the country and the proximity to New York, two hours away. [Bobby Van’s] was just a meeting place. You didn’t come just for the food⎯although of course food was provided⎯but to talk and visit.”

As it turns out, we have trouble following Gloria’s phone-directions and have to settle for being in the vicinity of Jones’ grave. For a second I think I smell cigar smoke. It’s easy to see why James Jones and his fellow writers and artists were drawn to this beautiful, quiet corner of America.

“They were looking for a home,” Marina says, still searching the grass for Jones’ grave marker. “Bobby Van’s gave them that. We were family.”

Lawrence Wells is a frequent contributor to hottytoddy.com. This article first appeared in Southwest Airlines “Spirit” Magazine.

Ron

September 6, 2014 at 4:54 pm

Great article, however, given how old the piece is, it might be worth adding the original publication date in a note at the top.

Coming across that reference to Scheider, who passed away in February 2008, is a little jarring.

Jane Henderson

January 25, 2015 at 9:33 pm

Oxford neighbor of Larry Wells. Live next door to Rowan Oak