Eating Oxford

Olive Oil, Part 2: Demystifying the Grades of Olive Oil

By Laurie Triplette

ldtriplette@aol.com

In this four-part series, food writer Laurie Triplette focues on demystifying olive oil, which has been a darling of the American food world for years. Triplette claims that the world of olive oil contains as many mysteries as most Southern families hide in our gene pools.

Click on the following links to catch up on the series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

PART 2: DEMYSTIFYING THE GRADES OF OLIVE OIL

To understand grades of olive oil produced from the “juice” of the olive, we must understand a bit about its botanical structure.

The olive tree is Olea Europea L. sativa, the domesticated cousin of the wild Olea Europea L. oleaster, native to the Mediterranean basin and most of the Middle East. They are both members of a family of Oleaceae that include jasmines, lilacs, and ashes. Olive trees flourish in the same climates where grapes grow, and take many years to reach full production. But they live for hundreds of years, and send out shoots from the roots, enabling damaged trees to regenerate. Many of the best olives in Europe and the Middle East are still harvested from trees that are hundreds of years old.

Where do olive oils fit into the world of cooking oils—and how do we make sense of different olive oils?

Olive oil is the only commercially sold oil that comes from pressing fruit rather than seeds (such as safflower, peanut, canola, soy) or tree nuts (such as walnuts and almonds). The olive fruit is a drupe (flesh that surrounds a seed, it is a stone fruit like cherries, peaches and plums). The olive flesh contains mesocarp cells that produce tiny droplets of oil — it is the end product of photosynthesis and is a means by which the olive tree provides a built-in energy storage system for nourishing olive seedlings in arid climates.

As soon as the olive separates from the tree, enzymes begin to break down the oil into a sort of compost surrounding the seed. The olive oil continues to deteriorate as the seedling is germinated. That’s why it is important for consumers to know which olive oils are made from picked olives rather than from fallen olives.

All olive oils are classified into three basic grades: Extra virgin, virgin, and olive oil. They are graded according their production method, acid content and flavors. There’s a fourth category called olive-pomace oil, which is oil created by a refining process involving hexane to extract the oil from the solid waste dregs (pits, skin and flesh) remaining after pressing out the better oils. Pomace is used for commercial purposes.

But here’s where it gets complicated. Extra virgin olive oil can be subclassified as premium or ultra premium extra virgin (the highest quality) or as extra virgin. Virgin olive oil can be further subclassified as fine virgin, virgin, or as semi-fine virgin. The olive oil classification includes what once were called pure olive oil and refined oil.

There is no universal grading standard applied internationally. Most countries adhere to the International Olive Council (IOC) standards. The Aussies have their own standards, the U.S. has its own, and Canada has its own system.

The difference in grading between the classifications of extra virgin and virgin depends on the acid content. Some grade differences can be only a fraction of a percent in difference. Olive oil experts have been trained to tell the difference, and consumers in the cradle of olive oil production (Spain, Italy, the Mediterranean and the Middle East) tend to know the difference from a lifetime of exposure to the good stuff. We Americans have a lot of catching up to do.

Olive oils’ characteristics and quality result from conditions as significant as those that produce the grapes for wines.

Olive oils’ characteristics and quality result from conditions as significant as those that produce the grapes for wines.These conditions include the variety of olive grown, the location and soil where it’s grown the weather during the growing season, the ripeness of the olives and HOW they are picked or gathered, the length of time between harvesting and processing, the actual method of processing, and the packaging and storage of the processed oil all affect the quality of the product.

To produce high quality oils, the olives must be harvested without breaking the fruit skins and should be processed within 12 to 24 hours of harvest. The olives are graded and separated by quality. Leaves and debris are removed by blowers rather than washing, and the olives are crushed into a paste. The oils can be extracted from the paste by pressing in a stone mill or hammer milling process, or by centrifugal decanting, selective filtration, or a combination of these methods.

The extra-virgin and virgin oils are made from the first pressing of ripe olives picked from trees, which removes about 90 percent of the juice from the olives. The juice in olives breaks out as about 20 percent oil and 80 percent water; the water must be removed during the pressing process. Extra virgin and virgin oils are not allowed to use chemicals or high heat for this, and no refined oils may be added to these oils. In other words, no additional processing or refining occurs to extra virgin and virgin oils after the first pressing.

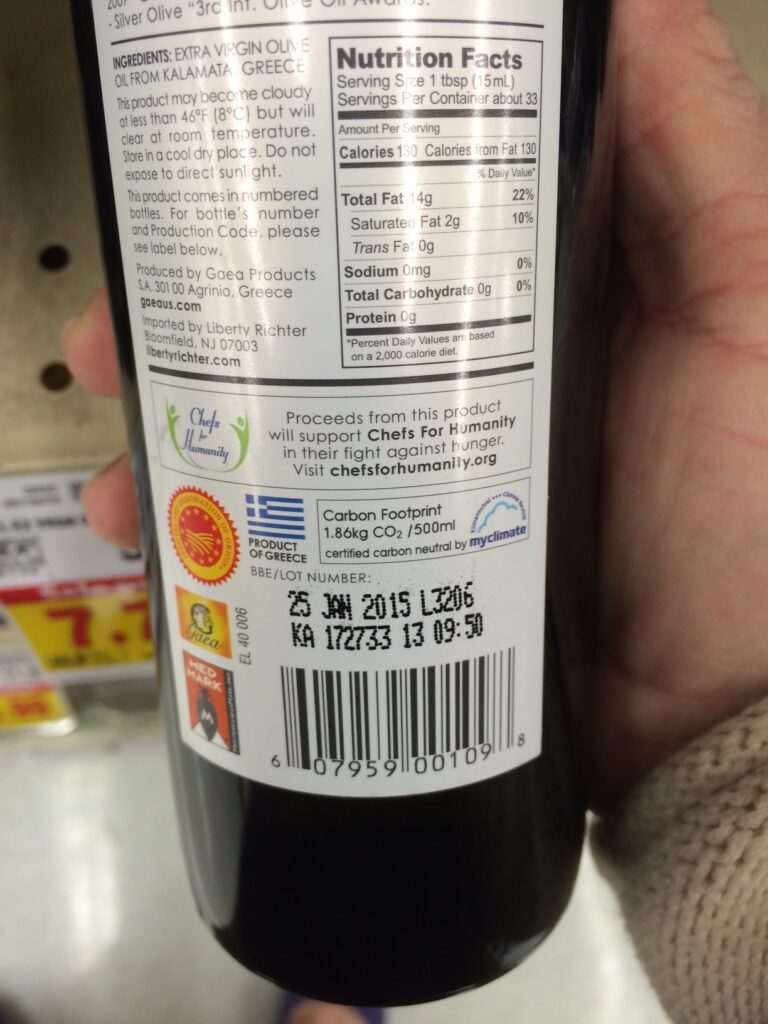

After processing, the oil should be store for 1 to 3 months to settle out any remaining fruit water and particulates. This eliminates sediment in bottles and also removes oil contact with processing-water residues that could taint the flavors. High quality oils will note the “first crush” dates on their bottling labels. Properly prepared and stored olive oil is good for about two years after first crush. Once opened, it’s good for about 6 months if stored properly away from heat and light.

The International Olive Council (IOC) is an intergovernmental organization founded in 1959 by the United Nations to supply advice to growers and millers, and to fund research in oil quality and chemistry. Headquartered in Madrid, Spain, it includes 43 member nations (including the European Union (EU) and EU nations). More than 98 percent of the world’s olive oil is from olives grown in IOC member nations.

The IOC Standards are as follows:

Premium Extra Virgin Olive Oil: Lowest acidity as low as 0.225 percent; best suited for adding to dishes uncooked such as salads, dips, and as a condiment on meats and veggies

Extra Virgin Olive Oil: No more than 0.8 percent acidity for IOC standards; with a fruity taste, ranging from pale yellow to bright green in color; also best used uncooked

Fine Virgin Olive Oil: Must have a “good” taste according to IOC standards, acidity no more than 1.5 percent;

Virgin Olive Oil: Must have a “good” taste and with acidity no more than 2 percent; cannot contain any refined oil, good for cooking or consuming uncooked

Semi-fine Virgin Olive Oil: Must have acidity no higher than 3.3 percent; excellent for cooking, not enough flavor to enjoy uncooked

Lite Olive Oil (also called Light or Mild): Has undergone extremely fine filtration process without heat or chemicals to remove most of the natural color, aroma and flavor; best suited for cooking or baking in recipes

The U.S. is not an IOC member. Our U.S. Department of Agriculture established its own standards in 1948, and does not recognize IOC classifications. In 2010, the USDA published the United States Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil.

The USDA standards for grading American olive are as follows:

U.S. Virgin Olive Oil: Virgin olive oil with reasonably good flavor and odor (not more than 2.0 percent acidity;

U.S. Lampante Virgin Olive Oil (also known as U.S. Olive Oil not fit for human consumption without further processing): Virgin olive oil with poor flavor and odor; intended for refining or for purposes other than food use;

U.S. Olive Oil: A blend of refined olive oil and virgin olive oils fit for consumption without further processing; has acceptable odor and flavor characteristics of virgin oil;

U.S. Refined Olive Oil: Obtained from virgin olive oils by refining methods that do not lead to alterations in the initial glyceridic structure; flavorless and odorless.

Like wine tasters, olive oil tasters sniff it first. They slurp it into their mouths, inhaling as they slurp to experience the olfactory sensory qualities of the oil. Good quality olive oil produces an astringent sensation in the back of the throat. The oil will smell and feel fresh and pleasant, with varying degrees of astringency, bitterness, or pepperiness.

Color also is important, although unscrupulous sellers have a history of altering color of inferior oils. Emerald-green-tinged olive oils come from unripe olives, and contain a slightly bitter flavor with overtones of fruity, grassy, peppery flavors. Golden colored oils are made from ripe olives, and contain a milder, buttery flavor.

Good olive oils are graded for positive attributes and for negative attributes. It seems counter intuitive, but the positive attributes of extra virgin olive are classified as follows:

Fruity: The basic positive attribute of virgin olive oils, from both ripe and unripe olives;

Bitter: The characteristic taste of olives that are green or turning color toward ripe, produced buy solutions of quinine, caffeine and various alkaloids;

Pungent: The biting sensation characteristic of oil produced at the start of the crop year, primarily from unripe olives (REF: IOOC, 1987)

The negative characteristics identified by professional tasters are called sensory defects, and may occur alone or in varying combinations.

Fusty: Olives were stored in piles that had gone through fermentation – think sour milk;

Musty: Moldy flavor from the fruit in which fungi and yeast developed as a result of being stored in humid conditions;

Muddy sediment: Left in contact with tank and vat sediment;

Winey-vinegary: Resulting from fermentation); rancid (oxidation and fragmentation into compounds;

Heated or burnt: Cooked flavors resulting from excessive heating during processing;

Hay or woody: Produced from olives that were dried out or frozen;

Greasy: Reminiscent of greases;

Vegetable water: Resulting from prolonged contact with liquid, nonoil component of the olive called fruit-water; Briny: Olives were preserved in brine;

Earthy: The olives were collected with earth or mud on them and not washed.

Both the positive attributes and sensory defects in olive oil are attributable to volatile compounds. As olive oil ages, its volatile compounds break down, forming increasing amounts of free oleic acid. As the acidity rises, the flavor diminishes.

Light and extra light olive oils are created by extra filtration and actually are refined olive oils. They do not have less fat than virgin and extra virgin olive oils, but do have less flavor, which makes them desirable for use in baking and frying. Light and extra light olive oils have a longer shelf life than extra virgin or virgin olive oils.

Fused oils are made by pressing high quality fresh olives with fresh fruit or veggies. Fused olive oils are called agrumato olive oil in Italy. Fused oils are less common than infused oils, but hold their flavor longer than infused oils and don’t turn rancid as quickly.

More than 90 percent of all fused olive oils are made in the Northern Hemisphere, at the end of the growing season mid-December through late January. This time frame eliminates the possibility for fusion of most fruits and veggies. That’s why most basil or garlic or vegetable flavored oils are infusions created by adding essential plant oils to olive oil.

Buyers need to be cautions when purchasing infused oils: Adding flavors is a trick often used by sellers when attempting to disguise poor quality olive oil. Even more outrageous is the usage of synthetic flavorings by some sellers.

Normal consumers who buy olive oil for home use constantly seek new ways of identifying good oils from bad. The smell test and the taste test remain the best barometers we can use.

It’s a myth that only extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) will coagulate when refrigerated. It is true that EVOO’s consist primarily of monounsaturated fats that coagulate under normal refrigeration temperatures. Also true is that low quality refined oils will not coagulate when refrigerated. Other oils used to adulterate olive oils tend to be polyunsaturated fats, which require much lower temperatures for coagulation. However, no two olive oils have the same monounsaturated fat consistency, and the fridge test is not accurate.

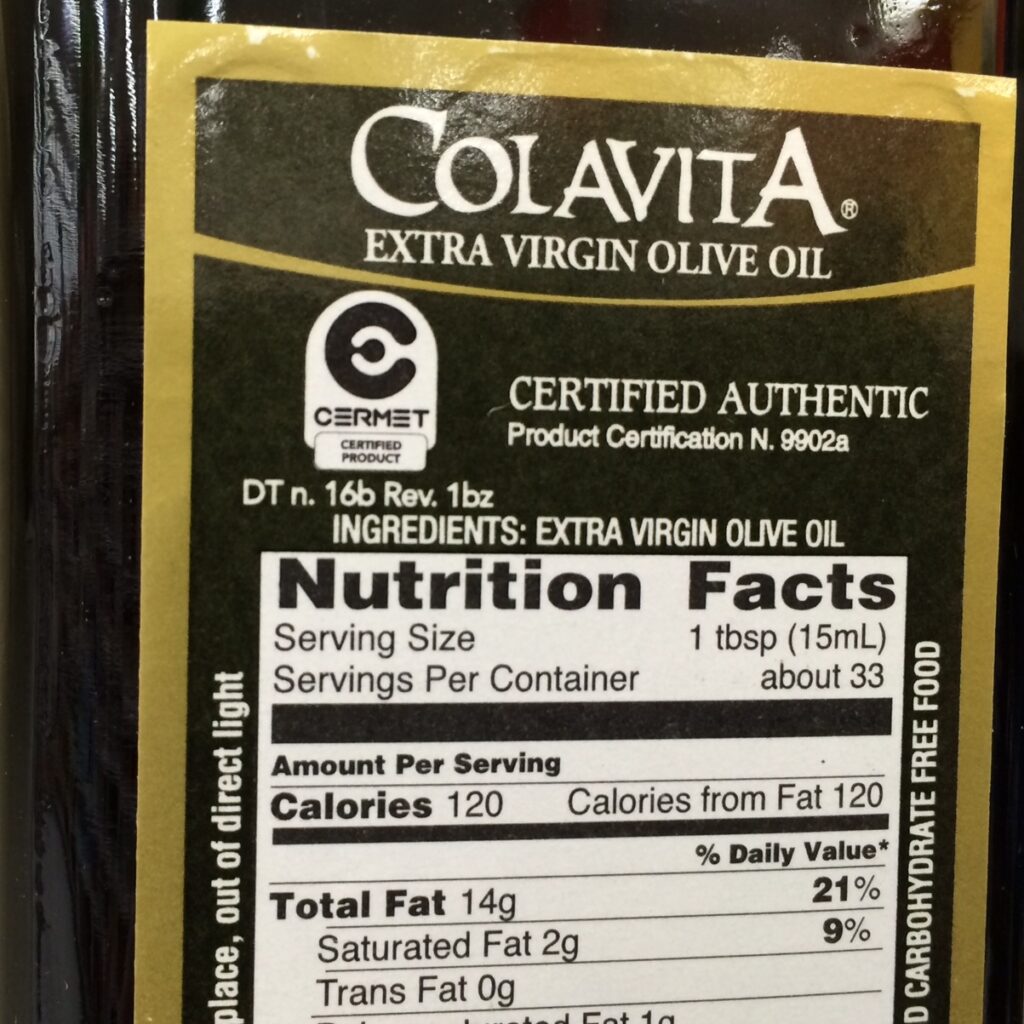

Experts recommend that American consumers look for quality seals on bottles of olive oil (North American Olive Oil Association Quality Seal or IOC seals). Also look for first crush dates, and country of origin in addition to country of bottling.

Next up: PART 3: Why Do We Care About Olive Oil? (Think Health Benefits)

Laurie Triplette is a writer, historian, and accredited appraiser of fine arts, dedicated to preserving Southern culture and foodways. Author of the award-winning community family cookbook GIMME SOME SUGAR, DARLIN’, and editor of ZEBRA TALES (Tailgating Recipes from the Ladies of the NFLRA), Triplette is a member of the Association of Food Journalists (AFJ),Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA) and the Southern Food and Beverage Museum (SOFAB). Check out the GIMME SOME SUGAR, DARLIN’ web site: www.tripleheartpress.com and follow Laurie’s food adventures on Facebook and Twitter (@LaurieTriplette).

You must be logged in to post a comment Login