Contributors

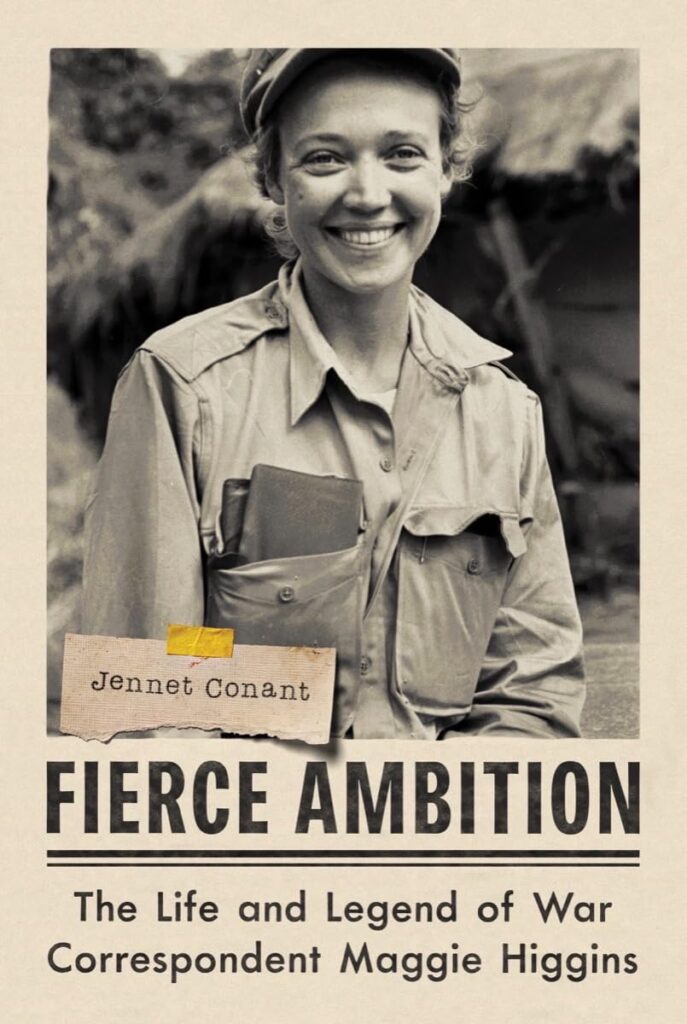

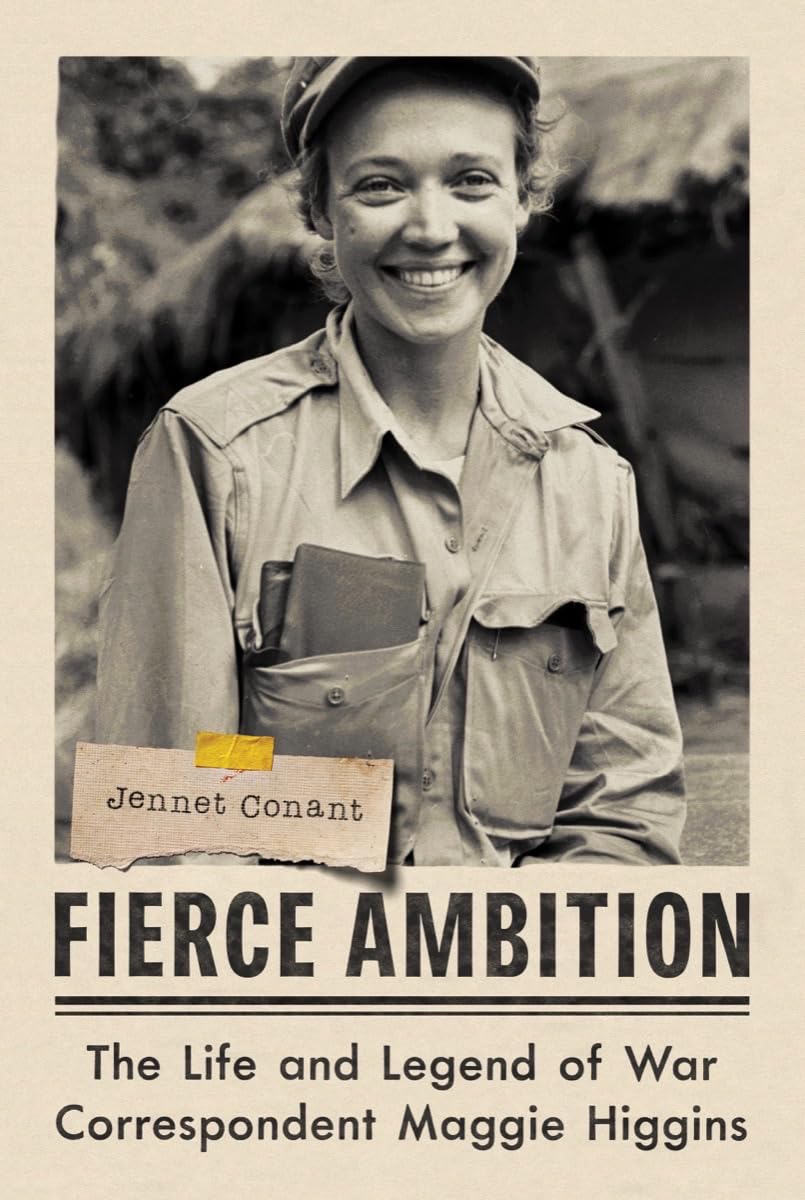

Allen Boyer Review – ‘Fierce Ambition: The Life and Legend of War Correspondent Maggie Higgins’ by Jennet Conant

Maggie Higgins was there when the GI’s liberated Dachau. “Mon Dieu, c’est une femme!” a

French prisoner shouted. Higgins was wearing a bulky soldier’s coat and a winter hat with long

ear-flaps, but the prisoner, a priest, knew an angel when he saw one.

Higgins reported for the New York Herald Tribune. Walter Winchell called her “the female Ernie Pyle.” She drew attention for her looks; she was a skinny bright-eyed blonde sorority girl from California – a Jennifer Lawrence of war correspondents.

But yet, as Jennet Conant shows in “Fierce Ambition,” Higgins took and held a place in the front rank of the reporters who covered World War II and the Cold War.

Higgins covered the Nuremberg Trials. In Berlin, with the Airlift going on overhead, she fired a Luger at a Soviet agent, one dark night, and another afternoon was trampled by a mob. In

Korea, a general kicked Higgins out of the combat zone; she appealed to Douglas MacArthur, and won. She went ashore with the Marines when they landed at Inchon (a seaborne assault that outflanked the North Korean army and almost won the war).

When the Pulitzer Committee awarded Higgins a prize for International Reporting, they cited her “fine front line reporting showing enterprise and courage … She is entitled to special consideration by reason of being a woman, since she had to work under unusual dangers.”

Higgins was dogged by rumors about love affairs. As Conant puts it, “she had never been one

of those women who are attracted to the straight arrows.” During the Twenties and Thirties, as

shown by Deborah Cohen in “Last Call at the Hotel Imperial,” America’s foreign correspondents,

Frances Gunther no less than John Gunther, had set new standards for sexual liaisons and

deadline reporting. In fact, the greatest advantage Higgins drew from her good looks was that

if she smiled and waved to a quartermaster sergeant, he would invariably gas up the jeep she

was riding in.

It was an era when news stories were written on a manual typewriter and filed by radio transmitter. That remained Higgins’ milieu; her interviewing style quickly proved too confrontational for anything more than what she called “practicing the art of tv” in San Francisco. She went back to New York City and the Herald Tribune, which sent her to Russia, the Belgian Congo, and Vietnam. She was three jeeps away from Robert Capa when the legendary photographer stepped on a landmine.

Higgins covered Camelot; she was one of the reporters whom JFK cultivated. In the end, Vietnam killed her. Higgins died a war correspondent’s death, an infection from the bite of a sand flea.

Jennet Conant has won recognition for several distinguished (and bestselling) books on the

scientific side of the Second World War. She has written on Robert Oppenheimer’s time at Los

Alamos, Roald Dahl’s espionage work in wartime Washington, Julia Child’s time with the OSS,

and how radar was perfected in the Hudson Valley estate of a reclusive tycoon (not impossibly inspiring the creators of Batman). “Fierce Ambition” is a book that Maggie Higgins would

rightly have respected.

Fierce Ambition: The Life and Legend of War Correspondent Maggie Higgins, by Jennet

Conant. W. W. Norton. 416 pages. $32.50.

Allen Boyer, book editor of HottyToddy, grew up in Oxford and now writes in New York City.