Arts & Entertainment

Allen Boyer: Review of “In Faulkner’s Shadow: A Memoir,” by Lawrence Wells

This Friday, September 18, 2020, at 5 p.m. Central Time on Zoom, Square Books is hosting Larry Wells in conversation with Bill Dunlap to discuss “In Faulkner’s Shadow.”

Editor’s Note: This Friday, September 18, 2020, at 5 p.m. Central Time on Zoom, Square Books is hosting Larry Wells in conversation with Bill Dunlap to discuss “In Faulkner’s Shadow.” Register to attend by emailing rsvp@squarebooks.com.

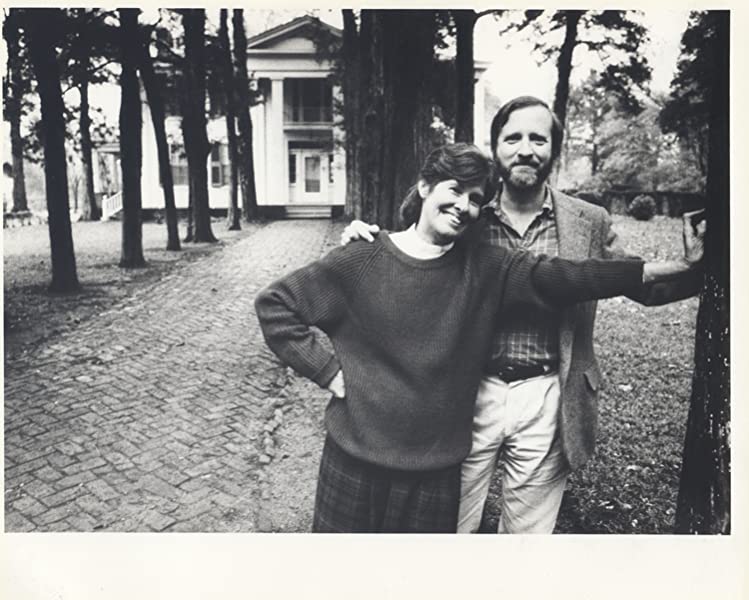

As the 1970s were opening, Larry Wells was a graduate student at Ole Miss. He met, fell in love with, and married Dean Faulkner, with whom he lived for the next four decades, enduring and prevailing and making a career in literature. That story and the milieu in which it unfolded are the subjects of Wells’ lively, pithy memoir “In Faulkner’s Shadow” – which shows that none of this was as simple as it sounds.

In this book, Oxford proves itself to be Southern literature’s company town. When a house fire explodes, the first fireman to arrive is Larry Brown. The mayoral candidate whom Wells backs in a crucial election is Square Books proprietor Richard Howorth. The friend who borrows a book and doesn’t return it is Barry Hannah (and the book is a signed, personally dedicated copy of William Faulkner’s “Big Woods”). Such a literary epicenter calls for its own publishing house – and Wells, although a novelist himself, is best known as the publisher of Yoknapatawpha Press.

Dean Faulkner was William Faulkner’s niece. In marrying Dean, Wells made himself an in-law of a family who he feels had hair-trigger tempers, drank too often, indulged themselves by taking offense, and let estrangements fester.

But William Faulkner is not really the central figure in this book. More of this memoir revolves around Willie Morris and Barry Hannah, two flawed crown jewels of the University of Mississippi English faculty. If Wells found himself in Faulkner’s shadow, he found himself at Willie’s elbow and alarmingly close to Barry’s line of fire.

This book provides a rarely nuanced portrait of Willie Morris. For once, Morris appears as more than a clown and a drunk. At parties, he could be a live wire. Wells recounts Dean’s recollections of one late-night gathering:

“We played finish the quote . . . . Then we played guess the college mascot . . . . At two-thirty, we matched fictional characters with book titles. At two-forty-five we named the US presidents. At three he asked if I knew the infield fly rule. Then he demanded pencil and paper and started planning his funeral. . . . The wake was to go on for a month. He asked me to bring pound cake.”

Morris might collapse into self-pity. He might make a foolish, presumptuous, earnest pass at a friend’s wife. However, when Morris was sober and focused, few journalists were better. Wells recalls the writing that Morris continued to work at, marveling at the man’s memory and recall. He forgives him much because of his skill as an editor, which Morris generously showed in mentoring student writers.

The book’s portrait of Barry Hannah is more troubling. Hannah appears as a reckless show-off and self-centered poseur. From the comfort of Square Books, “he chain-smoked, drank cinnamon coffee, and scribbled story ideas about drifters, dope dealers, whores, thieves, killers, and ordinary tradesmen with violent tendencies. ‘My work is about pain,’ he said.”

“Fiction to Hannah, I think, was a kind of therapy, highly superior to life,” Wells reflects, charitably. Unpredictably, Hannah abused and cursed out his friends. He talked about violence. He brandished firearms. He behaved so crudely and randomly that it seemed likely he might get someone killed.

“Willie wanted to be loved, Hannah wanted to be feared,” Wells concludes. “If Faulkner was as dark as night and Hannah a shadow-boxer, Morris was a lost soul searching for home.”

This is a memoir, but Wells talks much more about others than about himself. It is only the rare self-reflective passage that sums up how much he himself has contributed to Oxford’s literature and culture:

“As I approached fifty I began searching for the Larry Wells that I’d been, the graduate student whom Dean told Sandra Baker she wanted to spend the rest of her life with – former college English instructor, writer, indie press editor and publisher, bass player . . . who had published two novels, scripted an Emmy-winning documentary, and optioned four screenplays.”

To the Yoknapatawpha Press, Oxford owes many debts. These include the publication of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield’s photographs, Glennray Tutor’s artwork, and two major works on the Riot and James Meredith – Kathleen Wickham’s study of press coverage, and Ed Meek’s war-correspondent photographs of the embattled campus.

This is the story of two lives and a marriage. It is the chronicle of a Southern literary generation, writers who have lived in William Faulkner’s landscape (even if their fiction was often closer to the God-haunted grotesquery of Flannery O’Connor). And it is the continuing story of Oxford – given its vicissitudes and triumphs, a city that can no longer be mistaken for Jefferson.

“In Faulkner’s Shadow: A Memoir.” By Lawrence Wells. University Press of Mississippi, 2020. 245 pages. $25.00.

Allen Boyer is Book Editor of HottyToddy.com. A native of Oxford, he once met Willie Morris for a drink in the bar of the Oxford Holiday Inn.