Arts & Entertainment

Allen Boyer: Review of “Behind the Rifle: Women Soldiers in Civil War Mississippi”

*Editor’s Note: Shelby Harriel, author of “Behind the Rifle: Women Soldiers in Civil War Mississippi,” will read and sign copies of her book today, Wednesday, July 10, at 5:30 p.m., at Off-Square Books.

“War was the domain of men. Yet, women, too, were behind the rifle,” Shelby Harriel writes. “They, too, made the ultimate sacrifice for their respective causes and lie beneath headstones marked as unknowns.”

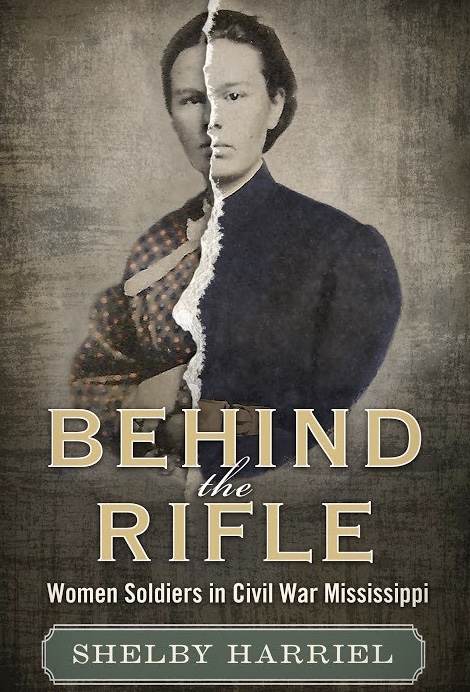

The two halves of the photo are two halves of two matched-set photographs taken of Elizabeth Quinn of the 90th Illinois Infantry. After serving as an enlisted man during the Vicksburg campaign, Quinn was wounded in Tennessee. Army nurses took photos of her, in a dress and in a uniform, and sold them to raise money for her.

This is a fascinating book – careful and confident when dealing with facts, shrewd when judging conflicts and choices, eloquent when speaking for those whose voices are lost to history. Drusilla Sartoris, Harriel observes, disguised herself to ride through war-torn North Mississippi with her uncle’s troop of partisans. Drusilla is fictional, one of Faulkner’s flawed heroines, but she may stand for many others. Like her, and very significantly, “the true women who fought in the Civil War chose to live an important part of their lives in contrast, rather than in comparison, to their peers.”

No woman who actually served as a Civil War soldier ever publicly expressed the desire “to actually exchange genders,” Harriel considers. “They did, however, indicate a simple longing for social and economic freedom that living as a disguised man afforded them . . . . After experiencing the liberation that trousers brought them, both literally and figuratively, it is little wonder that women were reluctant to return to torturous corsets and a restrictive domestic sphere.”

Opening with a broad look at women who served during the Civil War, this history focuses on Mississippi. (It is not only Mississippi-born women whom Harriel profiles; many of her heroines came south with Midwestern regiments in U.S. Grant’s army, and saw action in the state.)

In Chickasaw County and Choctaw County, local women organized companies of a Confederate home guard. Among those who marched off to war, many were teenagers with their hair cut short (like the beardless boys who were also joining the armies). Some were vivandières, sutlers who traveled with troops on the march – cooking, washing, sewing, selling provender and sundries. Such approved “daughters of the regiment” often wore jackets styled to look like uniforms, with trousers under their skirts. Others were prostitutes traveling with the army, hoping for business; some were former prostitutes who rebelled against that life and ran off to escape it.

The women of the Civil War endured newspapermen’s spoof reports that a “coloneless” was mustering a regiment of “female artillerists” to defend New Orleans, as well as predictable jokes about “a formidable display of breastworks.” They fought at Shiloh, at Iuka and Corinth, in every battle during the Vicksburg campaign, and with Mississippi regiments in the east, at Peachtree Creek. Some were unmasked when they were wounded, others when they were captured, some by burial parties. One was sent home when her dainty way of pulling on her socks drew attention.

The first documented case of a Mississippi woman serving as an enlisted man was charged with peculiar ironies. In Natchez, on April 18, 1862, a young runaway slave woman, “a bright colored girl,” took the name of William Bradley and signed on with Company G of Miles’ Legion, a Confederate unit – possibly for the enlistment bonus. She trained and drilled for weeks, until a passerby, her old master, recognized her. No one else had noticed either that she was a woman or that she was black.

In the Vicksburg campaign, when Van Dorn raided federal supply lines, Elizabeth Quinn fought at Coldwater Station, in the ranks of the 90th Illinois Infantry. She may have fought alongside a brother or been allowed to accompany her husband when he enlisted, or enlisted on her own, married a comrade, and continued as a regimental vivandière. All of those stories wrapped around Quinn – a teenager with a troubled home life, who had already reinvented herself as Frances E. Hook (the first of many aliases).

Quinn survived a leg wound, which brought her attention of war correspondents. Nurses raised funds for her by selling two photos, one in which she wore her uniform, another in which she modeled a boldly patterned dress. Those likenesses grace the cover of this book.

At Vicksburg, and later at Brice’s Crossroads, Jennie Hodgers fought as Private Albert Cashier. She served out her enlistment, maintained her identity, and worked odd jobs (farmhand, handyman, janitor). She voted in elections. A quarter-century after the war, Hodgers applied for and received a veteran’s pension. Only in 1911, when her employer backed into her with his car and broke her leg, was her secret revealed. That made little difference. Hodgers’ old comrades loyally visited her in the state veterans’ home, and, when she died, the local post of the Grand Army of the Republic saw that she was dressed in her uniform and buried with full military honors.

Hodgers rests in her native Illinois, but her story echoes in Mississippi. “To this day,” Harriel concludes, “Jennie Hodgers’ ruse continues to deceive,” as “visitors to the Vicksburg National Military Park gaze upon the name of Albert D.J. Cashier etched upon the tablet for Company G, 95th Illinois Infantry, inside the Illinois monument.”

Harriel teaches at Pearl River Community College. As a researcher and historian, she has published broadly, in journals and newspapers, online, and in brochures issued by the National Park Services. Her new book is a fine one, and it has been handsomely produced by the University Press of Mississippi.

“Behind the Rifle: Women Soldiers in Civil War Mississippi.” By Shelby Harriel. University Press of Mississippi. 207 pp. $25.00.

Allen Boyer is Book Editor for HottyToddy.com. His most recent book is “Rocky Boyer’s War” (Naval Institute Press), a Pacific War history drawing on his father’s diary.