By Alyssa Schnugg

News Editor

alyssa.schnugg@hottytoddy.com

As a Federal Court Judge, Michael P. Mills spends countless hours discerning fact from fiction and seeking truth among lies. In two days, Mills, along with about 20 other William Faulkner enthusiasts, will head to Boston to find a plaque memorializing a fictional character, but whose struggles ring true with many of his fellow Southerners.

Quentin Compson III is a character featured in two of the Pulitzer-winning author’s novels – “The Sound and the Fury” and “Absalom, Absalom!”

Set in the early 1900s, Compson was sent to Harvard to help restore his family’s reputation, where he finds himself alienated as one of the only Southerner’s at the school. Living with the sins of the South and his family members, he is driven to end his life by tying flat irons around his ankles and jumping off the Anderson Memorial Bridge (known then as the Great Bridge) into the Charles River.

In 1965, a small plaque memorializing Compson was placed on the bridge that read: “Quentin Compson III. June 2, 1910. Drowned in the fading of honeysuckle,” which was a reference to “The Sound and the Fury,” where Compson made the observation that “there were vines and creepers where at home there would be honeysuckle.”

The plaque disappeared in 1983 and a new plaque was put up with a slight change in the wording. The new plaque reads: “Quentin Compson drowned in the odour of honeysuckle. 1891-1910.”

The plaque is small and finding it became a popular scavenger hunt for Faulkner fans throughout the last few decades.

The Legend and the Pilgrimage

In 1985, Dale Russakoff wrote a story in the Washington Post titled, “Faulkner and the Bridge to the South,” that explains what it means to be a lonely Southerner in the North.

“Quentin Compson III is a symbol of the sense of loss and maybe regret, among other feelings, that many Southerners feel,” Mills said.

Russakoff’s story helped inspire Mills and his group of “Mississippi Pilgrims” to travel to Boston where they will “seek to bridge the chasm between past and present, truth and fact, North and South, in Faulkner’s fiction,” Mills said.

Mills, along with UM Professor Emeritus of History and Southern Studies Charles Reagan Wilson and Mississippi Sen. Hob Bryan will be driving to Birmingham, Alabama on Wednesday to ride the Amtrak Creasant to Atlanta, Washington D.C. and New York City.

Along the way, other “pilgrims” in those cities will join the group on the train, while others will join in Boston. The group will be meeting at the Commander Hotel near Harvard.

On June 2, the anniversary of Compson’s suicide, the group will seek out the plaque, some dressed as characters from Faulkner’s novels while reading personal essays on their interpretation of Faulkner and the South and what it means to be a Southerner today.

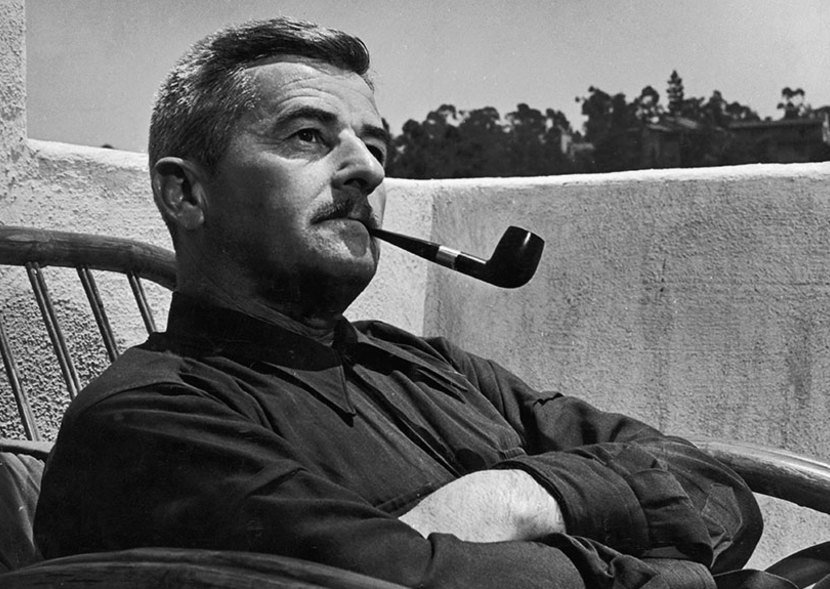

Photo provided

Other “pilgrims” attending the trip include Sen. Roger Wicker, Jackson attorney Jay Wiener and former Supreme Court Justice Jimmy Robertson.

Mills said the “pilgrims” are a group of people who have a “shared interest in the literature of Faulkner.”

Wilson, who served as the Kelly Gene Cook Sr. Chair of History and Professor of Southern Studies at the University of Mississippi, where he taught from 1981-2014, said he’s intrigued by the opportunity to commemorate a singular event from “The Sound and the Fury,” in what he calls Faulkner’s greatest novel.

“One of my research projects is on the Southern way of death, and this trip offers a way to ponder, through a collective ritual a hundred years after the event, the meaning of Quentin’s suicide,” Wilson said. “It occurred at a particular moment of time, in the early 20th century, when the South was trying to reconcile its obsessions with the past, with the Old South and the Confederacy, at the same time that the winds of modernity were blowing, as more cities grew, commercial activity increased, agriculture was beset by sharecropping and on a downward spiral for many southerners.”

While the pilgrimage is about honoring Faulkner and his character, the underlying theme of suicide is still a very real problem in today’s society, Wilson added.

“This trip gives me the occasion to read Faulkner, to study up on Quentin in particular, to recognize that suicide is a continuing plague among many American young people, and to empathize with those trials that Faulkner probed with his usual profundity,” Wilson said.

A Connection with Fiction

After reading Russakoff’s article, Robertson felt an immediate connection with Compson.

Robertson, raised in Mississippi went to school at Ole Miss in the early 60s before attending Harvard Law School.

“I remember getting to Harvard and thinking, ‘Oh my God, what have I gotten myself into?’” Robertson said. “It was a very different atmosphere than Ole Miss in a half dozen aspects.”

While at Ole Miss as an undergrad, Robertson and his history class went to Rowan Oak where they met Faulkner who poured them glasses of whiskey and spent most of his time chatting with the female classmates.

While at Ole Miss as an undergrad, Robertson and his history class went to Rowan Oak where they met Faulkner who poured them glasses of whiskey and spent most of his time chatting with the female classmates.

“Truth be told, it wasn’t much of an evening for the guys,” wrote Robertson in an essay about Faulkner. “On the other hand, it was one of those moments among my nigh unto 79 years on this planet when I met and shook hands with the likes of Ted Williams and Rudolph Nureyev and Leonard Bernstein and a handful of mere presidents of the United States.”

A few weeks after arriving at Harvard in 1962, riots broke out at Ole Miss over the desegregation of the university as James Meredith, an African American, was escorted onto campus. Two men were killed in the riots. More than 3,000 federal soldiers were called in to stop the violence.

“I’m not trying to force my experiences as the same as Quentin’s, but there were some common themes,” Robertson said. “I was one of two Mississippians there at the time. I felt the pressure and it was tough in many ways.”

In 1979, Robertson moved to Oxford and became a faculty member at the University of Mississippi School of Law. Faulkner’s fan base at Ole Miss had grown along with the creation of the Faulkner Conference. In 1984, Robertson found himself with six weeks off and decided to spend his break immersing himself in Faulkner. He read seven novels.

Robertson and Mills would often discuss their thoughts on Faulkner’s work.

“At some point in our discussions, I’m sure I mentioned the 1985 article and going there to find the plaque,” Robertson said. “We’ve talked about it off and on throughout the years.”

Keep track of the “Mississippi pilgrims” as they make the trek to Boston and the Anderson Memorial Bridge to locate Compson’s plaque later this week as the group sends back photos that will be published on Hottytoddy.com.