Southern Experience

Reform or Removal—The Fate of the Chickasaw Nation

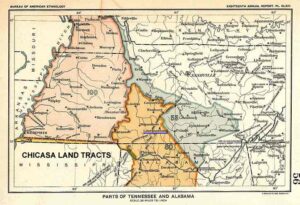

Over the last few weeks, I have endeavored to give you some historical information on the Chickasaw Nation and the people who were the first to come to “our little postage stamp of native soil.” At first these people had this area of present day Mississippi and the old Southwest all to themselves. Their ancestral lands covered much of North Mississippi, West Tennessee and Northwest Alabama.

This was their land for many centuries until first the Spanish, then the French, then the English and at last the Americans began to covet their land. The Europeans made strides to either change the Indians way of life, first for diplomatic purposes and then for economic purposes. As time marched on, although some changes were made in the Indian-way of life, these noble caretakers of the land were forced over and over to relinquish their land to the white man.

Over a period of just over twenty years the Chickasaw were required to move and sell to the federal government a little over twenty-six million acres of land. It all started with an agreement in 1801 for the United States to make a wagon road through Chickasaw territory. The wagon road was to follow the course of the Natchez Trace, a path long used by traders which connected Nashville with Natchez. The Indians accepted $700 in exchange for allowing this wagon road to be blazed through their lands.

This first treaty caused President Thomas Jefferson to propose a plan, of which he said the objective of the federal government was to, “establish among the Chickasaw a factory for furnishing them all the necessities and comforts they may wish (spirituous liquors excepted), encouraging them and especially their leading men, to run in debt for these beyond their individual means of paying; and whenever in that situation, they will always cede lands to rid themselves of debt.”

A few year later, in 1805, another treaty granted the federal government all Chickasaw land north of the Tennessee River. The tribe received $20,000 for this cession, of which more than half went to pay the tribe’s debt of $12,000 at the Chickasaw Bluffs trading post. The Chickasaw Bluffs is now the City of Memphis.

At this time there was debate in Congress and among the white settlers in the area as to whether “reform” or “removal” should be the actions taken against the Chickasaw Nation. Removal had been the last thing the Europeans wanted when trade first developed with the tribe. They, the tribe, had diplomatic and military importance in contesting rival powers, the Spanish and the French, along with the British settlers. Indians were essential to harvesting deer and other products for commercial profit. All of this had changed by the time the Americans took over.

The economic value of skins and forest products declined at the same time as the international struggle changed with the advent of the United States. Americans began to debate two Indian policies—-reform or removal. Historian Don Doyle writes, “What American wanted instead was the land the Indians occupied.”

One group of Americans sought to reform the Indian way of life and wanted to help them assimilate into the white civilization. Another group advocated removing the Indians to the West, and as Doyle states, “on the premises that Indians could not readily assimilate and for their own protection, needed to be isolated from the corrupting effects of white contact.”

To transform the Indians from hunters into farmers and to assimilate them within a Christian, English-speaking society proved to be too difficult. “Removal” rather than “reform” eventually became the goal of the Americans. Indians were a dangerous threat to the safety of white settlers. The encroachment of white traders, swindlers, and liquor dealers became the norm and the argument of Americans was that their removal was for their own good.

Thus a series of treaties slowly reduced the land occupied by the Chickasaw. In 1816 a treaty resulted in the loss of the Chickasaw’s title to all of their territory stretching from the south side of the Tennessee River to the west bank of the Tombigbee River. This treaty called for a $12,000 annuity (annual payment) to be paid by the government to the tribe for ten years.

The next treaty came in 1818 when the Chickasaw nation ceded all their land north of the southern boundary of the State of Tennessee. For this territory the government paid a fifteen year, $20,000 annuity. The Chickasaw had now ceded nearly twenty million acres of the traditional Chickasaw homeland.

What now remained was a little over six million acres in northeastern Mississippi and a small tract in present day northwestern Alabama. The Treaty of Pontotoc Creek would cause the cession of the last of the Chickasaw land east of the Mississippi in 1832. This treaty will be the subject of my next column on the once proud and noble Chickasaw Nation.

— Jack Lamar Mayfield is a fifth generation Oxonian, whose family came to Oxford shortly after the Chickasaw Cession of 1832, and he is the third generation of his family to graduate from the University of Mississippi. He is a former insurance company executive and history instructor at Marshall Academy in Holly Springs, South Panola High School in Batesvile and the Oxford campus of Northwest Community College.

In addition to his weekly blog in HottyToddy.com, Mayfield is also the author of an Images of Americaseries book titled Oxford and Ole Miss published in 2008 for the Oxford-Lafayette County Heritage Foundation. The Foundation is responsible for restoring the post-Civil War home of famed Mississippi statesman, L.Q.C. Lamar and is now restoring the Burns Belfry, the first African American Church in Oxford.

The blog is based on columns he has written for the local newspaper and will cover more the 400 columns previously published.