Sept. 18, 1830: Roughly 6,000 Choctaws were camped out at Dancing Rabbit Creek in Noxubee County to await a decision they had long dreaded.

Emissaries from the president of the United States were there to meet them, intent on negotiating a treaty that would require the Choctaw to move to southeastern Oklahoma.

Over the span of 10 days, amid a carnival- like atmosphere, U.S. Commissioners William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) and John Coffee plied Choctaw chiefs with offers of money and land but steadfastly insisted that the tribe needed to leave Mississippi. Prostitutes, gamblers and whiskey salesmen were welcomed. Missionaries were barred.

Choctaw negotiators Greenwood Leflore, Mushulatubbee, and Nitakechi, leaders of a delegation of 20 chiefs, must have known resistance was futile. The tribe had seen Gen. Andrew Jackson’s army decimate the rebellious Creeks and defeat the British and the French. They knew how quickly the American military with its superior firepower could destroy a tribe. They knew, too, that Jackson, now president, would not hesitate to use force.

The tribe that in 1815 helped Jackson defeat the French at the Battle of New Orleans, the tribe that helped him defeat the Creeks, was being forced by their old ally to give up their last 10,423,130 acres in Mississippi and become the first Southeastern tribe exiled to Oklahoma.

The cause of Jackson’s change of heart towards the Choctaw: money, land, and demand.

Since 1798, when the Mississippi Territory was formed, droves of white settlers had flocked to the Choctaw homeland in central Mississippi. Before long, they outnumbered the Choctaw. By the time Mississippi became a state in 1817, there was an insatiable hunger for Choctaw land to accommodate the growing white population.

Land. It was always about land.

And cotton. White gold.

The cotton gin and African slaves had suddenly turned the white fluffy stuff into the world’s single most valuable commodity. Its promised riches fed a frenzied land rush that put enormous pressure on politicians from Mississippi to Washington. But before they could take the land, they had to be rid of the Indians. So in 1829 the Mississippi Legislature passed a law making it illegal for anyone to claim membership in a tribe or to call themselves chief. The following year, Jackson pushed through Congress the Indian Removal Act, which prompted the final treaty negotiations.

The Choctaw desperately wanted to remain. But Clark and Coffee made it clear that their fate was already sealed. With a cash payment to the tribe ($20,000 a year for 20 years) and government assistance to move west continuing to be the only offer, the chiefs realized their options were limited.

As a further enticement, each of the three chiefs was promised 2,560 acres of land; Chiefs Greenwood Leflore and Nitakechi would receive annuities of $250 for the rest of their time in office, and Mushulatubbee would receive an annuity of $100 while he held office.

There were no other options. Sign and be moved — but live — or don’t sign and be killed.

Three chiefs, two options, one choice.

On Sept. 27, 1830, in a fog of alcohol, gifts, and threats of force, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed.

With the stroke of a pen, the lives of the Choctaw changed forever.

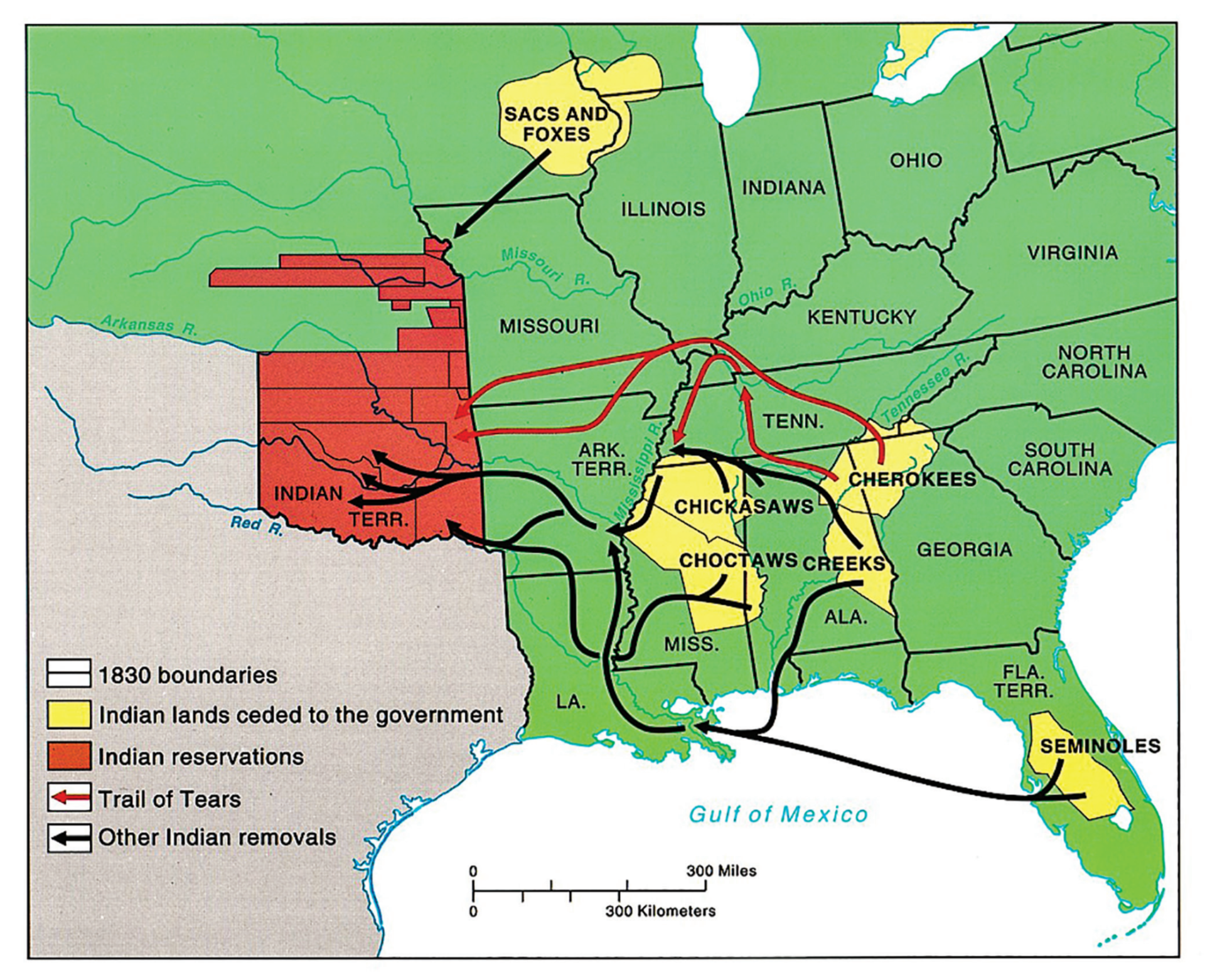

Approximately 17,000 tribal members trudged to Oklahoma the following year. During the brutal march through snow and freezing weather with few blankets and not enough food, about 2,500 died. The death march would later be known as “the Trail of Tears.”

But not every Choctaw left.

Some 4,000 to 6,000 remained in Mississippi because of a provision in the treaty that promised individual allotments of land to Choctaws who would leave the tribe and apply for U.S. citizenship within six months.

They were soon to be disappointed.

The agent assigned to collect their applications “deliberately prevented many tribal members from taking advantage” of the provision, according to James Barnett’s Mississippi’s American Indians.

Indian Territory. Copy Photo

“During that removal to Oklahoma, you had people that stayed back and got swindled out of their little piece of land that they had,” says Jay Wesley, director of Chahta Immi, the cultural preservation agency for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

By the deadline, only 69 heads of families were able to obtain their land. Even those who got land soon had to sell it to survive. Others lost it to whites through fraud and intimidation. The Mississippi Choctaw disappeared into the woods and swamps or scratched out a meager existence sharecropping.

Once, the Choctaw controlled two-thirds of what is now Mississippi. In The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic, historian Angie Debo wrote that the Choctaw were known for their “peaceful character and their friendly disposition.” She called the tribe practical and adaptable, without elaborate emphasis on religion or ceremony.

For hundreds of years before white men arrived, the tribe lived on gardening and hunting. The unspoiled forests were thick with game, the rivers rife with fish. They developed a highly organized society and actively traded with other tribes, demonstrating a natural talent for business. For a time, some Choctaw would practice head flattening as a ritual adornment, but the practice fell out of favor.

Life took a drastic turn in the 1700s when the French and British began to colonize North America. British traders supplied the Chickasaw to the north with guns, which they used to attack the Choctaw, taking slaves to trade to the British.

When the French established a beachhead along the Gulf Coast, the Choctaw got their revenge. They allied with the newcomers, trading deer-skins, baskets, and other hand- made goods for guns, which they used to stage periodic raids on the Chickasaw. The French, eager to keep this alliance and expand their influence northward, would reward the chiefs with gifts and honorific “titles.”

The Choctaw became skilled diplomats through their time trading with the French, squeezing them for more and more gifts. But they kept their promises, going to war with the Natchez and the Chickasaw on behalf of the French and continuing trading with them until the French and Indian Wars, when the British defeated the French.

After the defeat of France, Britain took over trade with the Choctaw.

Life for the Choctaw changed again when the British were defeated in the Revolutionary War. Over the next 44 years, the Choctaw were pressured into signing nine treaties with the United States.

The first, the Treaty of Hopewell in 1786, was supposed to clarify the boundaries of the tribe. In return for the protection of the United States, the tribe ceded 69,120 acres of land.

Hopewell was important because, as Wesley says, “[T]hat started everything else… We didn’t understand that piece of paper, of deeds and titles and so on and so forth, so what are we signing? Start giving them a little then [they think], ‘Hey, we can get land from these people.’”

The Treaty of Fort Adams in 1801 was next. The Choctaw ceded 2,641,920 acres.

It was never enough. As more settlers poured in, more treaties were negotiated, each one giving the U.S. more land — more than 23 million acres in all — and promising that the tribe would be left alone. That promise would be broken again and again. It seemed that Americans could never get enough.

The tribe tried hard to adjust, to get along with the newcomers, even adopting their dress and many of their customs. Many Choctaw became fairly prosperous farmers and merchants. One chief, Mushulatubbee, even ran for Congress. All to no avail.

Finally, the Treaty of Doak’s Stand in 1820 set aside land in Oklahoma as a future home for the Choctaw and the government’s intentions were painfully clear: removal.

The tribe’s old ally, Andrew Jackson, led negotiations himself. For three long weeks, Jackson badgered the chiefs to accept the arrangement. The tempestuous general pushed his old partners hard, alternating between syrupy promises of desirable land out west and bald threats of violence. When the charismatic Chief Pushmataha accused him of deceiving the Choctaw about the quality of Oklahoma land, pointing out that white settlers were already living there, Jackson grew enraged.

Finally, the treaty was signed by U.S. representatives Jackson and Thomas Hinds and Chiefs Pushmataha, Appuckshunubbee, and Mushulatubbee. It ceded 5.1 million acres in exchange for the land in Oklahoma.

Ten years later came the infamous Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, followed by removal of most of the Choctaw to Oklahoma.

For those who stayed behind and hunkered down in Mississippi, life was hard. “We were in the swamps hiding,” said Wesley. “We were part of a sharecropping system.”

The turn of the 20th century saw the dwindling band of Choctaws in despair. By the early 1900s, Congressional investigators called them “the poorest pocket of poverty in the poorest state in the country.” It didn’t help that in Mississippi’s segregated society, the Choctaw faced the same discrimination that black people faced. In time, even the tribe’s culture would come under attack.

“We have been taught to be ashamed of ourselves,” said Harold (Doc) Comby, who lives on the Choctaw reservation near Philadelphia today.

“[I]n grade school, when we spoke our language, the teacher would make the students open their hands like this and spank it with a wooden ruler. When you get punished for speaking your language, you start feeling bad about yourself,” he said.

When it could not have become any worse, it did. Disease struck. The flu spread like fire, killing hundreds. By the time the epidemic passed, fewer than 2,000 Choctaw were alive.

Finally, help arrived. In 1918, the U.S. commissioned the Bureau of Indian Affairs to look into the condition of the people. With a budget of $75,000 — about $1.2 million today — the BIA built schools and made an initial purchase of 15,000 acres for the Choctaw.

It took a while, but eventually they were able to adopt their own constitution. And, in 1945, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians received formal recognition from the government.

The tribe was still mired in poverty. With white supremacy the law of the land in Mississippi, Choctaw were not allowed to vote in local and state elections. They could not attend all-white public schools. They were steered toward the back doors of restaurants. The tribe relied heavily on government support and unemployment was at nearly 80 percent. Alcoholism and depression were rampant.

Will Campbell, a Baptist minister, civil rights activist and author, wrote of “the depressing sight of the Choctaws, their shanties along the country roads, grown men lounging on the dirt streets of their villages in demeaning idleness, sometimes drinking from a common bottle, sharing a roll-your-own cigarette, their half-clad children a picture of hurting that would never end.”

But a savior was on the way.

Phillip Martin, having served in the Air Force in Europe and seeing how Germany was able to rise from the rubble after World War II, determined that the Choctaw could do the same. He was elected chief in 1979 and began the process of rebuilding the tribe.

He knew the tribe would never escape poverty if it continued to depend on the federal government. He advocated a philosophy of self-determination, encouraging the tribe to lift itself up.

To succeed, he needed jobs, and lots of them. He encouraged the tribe to build an industrial park and began recruiting industry. In time, he was able to persuade the city of Philadelphia to issue bonds to help him pay for a 12,000-square-foot building and used it lure a business that made greeting cards. It created 250 jobs. He secured a plant that installed spaghetti- like wire harnesses in automobiles. He purchased First American Printing and Direct Mail Enterprise and the First American Plastic Molding Enterprise. Suddenly, Choctaw had a few hundred good-paying jobs and could support their families.

In 1994, the tribe opened the first of its three gambling casinos, which dramatically improved employment on the reservation. Ultimately, unemployment fell to about two percent.

Now, Chief Phylliss Anderson, a Martin disciple, runs the tribe. She is its first female chief.

And today the Choctaw, the only remaining indigenous tribe in Mississippi, have become an inspiring success story of what can happen when people seek to control their own destiny. The tribe boasts more than 10,000 members, not counting one-quarter Choctaws who are allowed access to federally funded services such as schools and the health center.

It has created nearly 6,000 jobs, making it one of the largest employers in the state. And average household income has grown from $2,500 in 1979 to more than $25,000 today.

Courted by politicians, depended on to prop up the economy of one of the poorest states in the union, and a model for what an embattled minority can accomplish, the Mississippi Choctaw did not simply endure, they have prevailed.

By Josie Slaughter

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw and Choctaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.