Featured

Unconquered and Unconquerable: The Prophet of Profit

The Silver Star and Golden Moon casinos command attention, towering symbols of the tribe’s economic success. Photo by Chi Kalu

It was in 1948 when Air Force Staff Sgt. Phillip Martin, future chief of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, first surveyed the fallen empire of Nazi Germany.

Thousands of miles from the dirt roads and pine forests of Neshoba County, Miss., once-pristine cities, the pride of a nation, a people, and a führer, lay in ruin. Buildings that remained after Allied bombings sat gutted. Mountains of rubble, retched from walls turned into gaping mouths, over owed onto German streets. Children ran barefoot, playing in front of once-stately cathedrals, now crumbling like stepped-on sandcastles. Mothers, desperate to feed these children, sifted and searched through garbage cans for remnants of food.

Reconstruction for what remained of Adolf Hitler’s Germany would not come easily. But it would come.

The Germans could be found rummaging through each singular pile of debris in their streets, pulling out the bricks and stacking them neatly. They chipped the mortar from decimated houses and offices and carted it away for reuse. Street by street, the piles disappeared, and a new Germany began to take shape, one block at a time.

In his mind, Martin was taking notes.

This was not the first time Martin had seen barefoot children. It was not the first time he had watched a desperate mother. In fact, as the son of a janitor, a product of an impoverished Native American tribe in a backwoods, mostly backward part of Mississippi, this was nothing new to him at all. But the stiff German resolve, a badly beaten nation, rebuilding itself piece by piece, brick by brick; this was very new. And it taught him something.

If this nation, shamed, shunned, all but obliterated, could start again, who was to say that his own broken tribe could not do the same?

With that thought in mind, Phillip Martin would return to the reservation that raised him, designs in hand to resurrect a broken people.

One could argue the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians was not just broken. It was shattered.

Until Martin’s election as chief in 1979, unemployment rates soared close to 80 percent, with the percentage suffering from alcoholism trailing close behind. After years of living under the hard-handed cultural repression of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a federal organization once dedicated to the subjugation and assimilation of Native Americans into mainstream society, the Choctaw lived a hardscrabble existence for decade upon decade with almost no means of self-government.

They had endured so much that to many, the idea of engineering their own fate, laws, and industry seemed almost an impossible task.

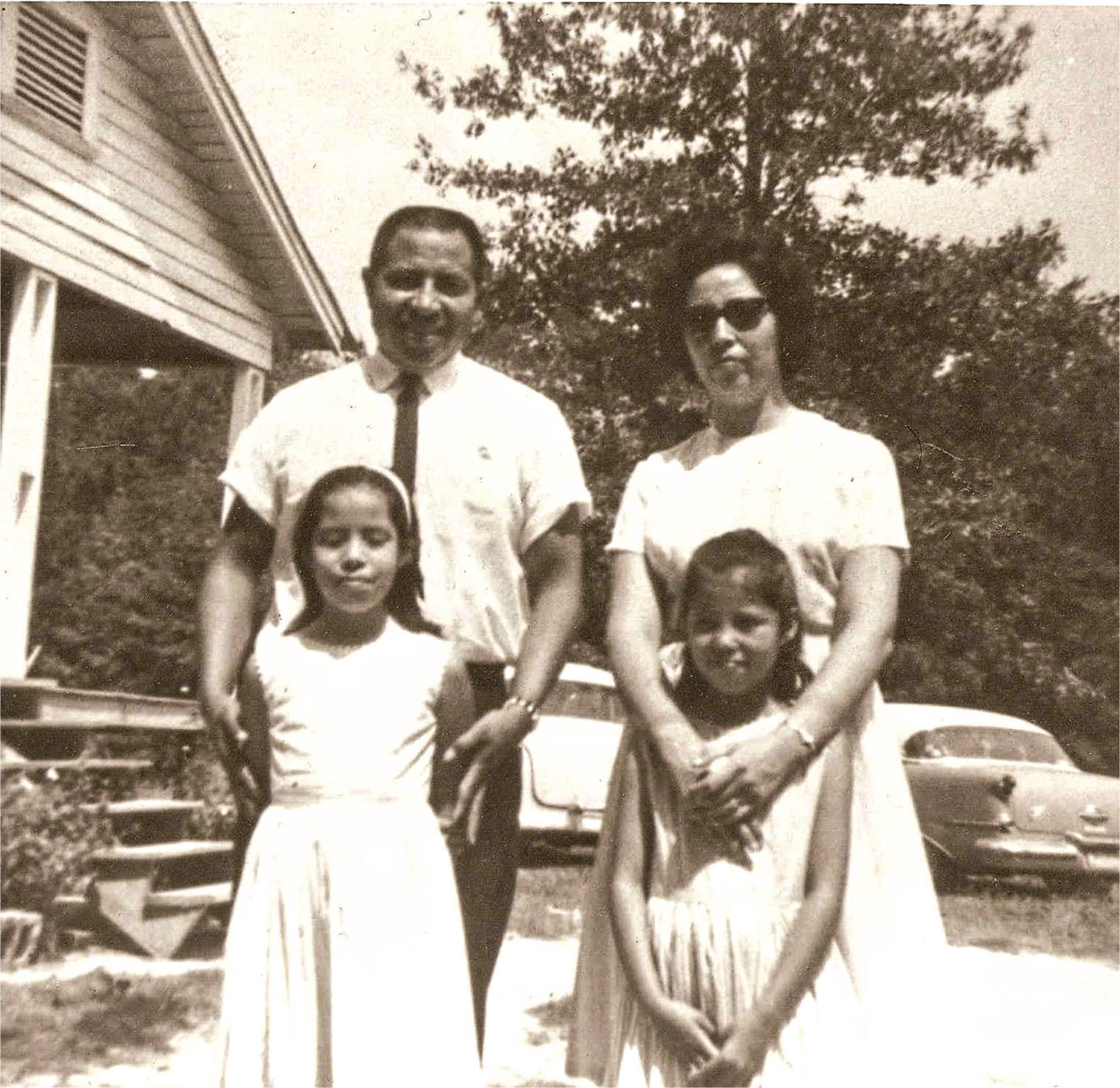

An early portrait of Phillip Martin and his family. Photo by Bob Ferguson

But to Phillip Martin, the ability to self-govern as a tribe, or “self-determination” as he branded it, would be the only way to break the cycle of poverty that had gripped his people for the better part of a century.

Martin was born into a typically poor Choctaw family in 1926. While he did benefit from luxuries such as electricity, a coveted utility most Choctaw did not possess, his childhood still consisted of the hardship typical for his people at the time.

After the hit-and-run death of his father in 1937, Martin and his siblings were mostly separated, with Martin being sent to a boarding school in Cherokee, N.C., one of many designed to bring Native Americans into mainstream American society and keep young Native American boys out of trouble. Martin would bide his time in Cherokee until 1946, when he would decide to join the military. He would not return home until 1955.

Fast forward to 1973, and the Choctaw were a little closer to improving their lot. The ability to make one’s own decisions was still very much a new concept to the tribe.

Nell Rogers, a white graduate student teaching in Philadelphia, was new to the Choctaw as well. During the tense and turbulent early years of school desegregation, Rogers was the kind of progressive, liberal young person many rural Mississippians would have found a terrifying enigma.

Martin, who in 1973 was an important member of the Choctaw Office of Tribal Planning, was busy drafting a dream team of both natives and outsiders alike to begin deciphering the best path to Choctaw recovery, an entirely different type of puzzle.

Volunteered into teaching the tribe’s new adult literacy program by her husband, Rogers suddenly found herself in charge of the Choctaws’ first-ever attempt at educating its own members, under the guidance of the man who saw education as a critical part of creating a strong workforce.

Rogers, who speaks of Martin the way many would speak of a John F. Kennedy or Ronald Reagan, recalls her time with him with obvious reverence.

There were many ribbon-cuttings when Martin, shown here with a Choctaw Princess, was chief. Courtesy of Mississippi

“He was talking to me and he said, ‘What is your vision of the adult education program?’ I was a ’60s person, so I said, ‘I hope that we can help them be happy people.’”

“Well,” Martin responded, “I’d hoped they’d be good workers.”

According to Rogers, this is the philosophy that would dig a community steeped in unemployment and alcoholism out of the crushing poverty that has plagued many Native American tribes since the Trail of Tears.

In 1975, Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, allowing eager tribal leaders such as Martin to begin leading their tribes away from the paternalistic policies of the federal government.

Martin was elected chief in 1979, and what had started as a few night classes soon began to branch into the creation of dozens of new facets of Choctaw development.

“Chief Martin is modern Choctaw government,” said Rogers. “It wouldn’t have existed. The structures of government didn’t exist — courts, judicial systems, and legislative systems. He was the first one of the tribal leaders in the country to embrace self-determination, and to begin to take over the operations of the federal government and have those run by the tribe.”

“To him, self-determination was the ability to make your own decisions, the ability to govern your people, the ability to use your own resources and apply them. He got the concept in spades of self-governing and making your own choices. He felt that tribes were able to do that and should do it, and by right under the Constitution could do it,” she said.

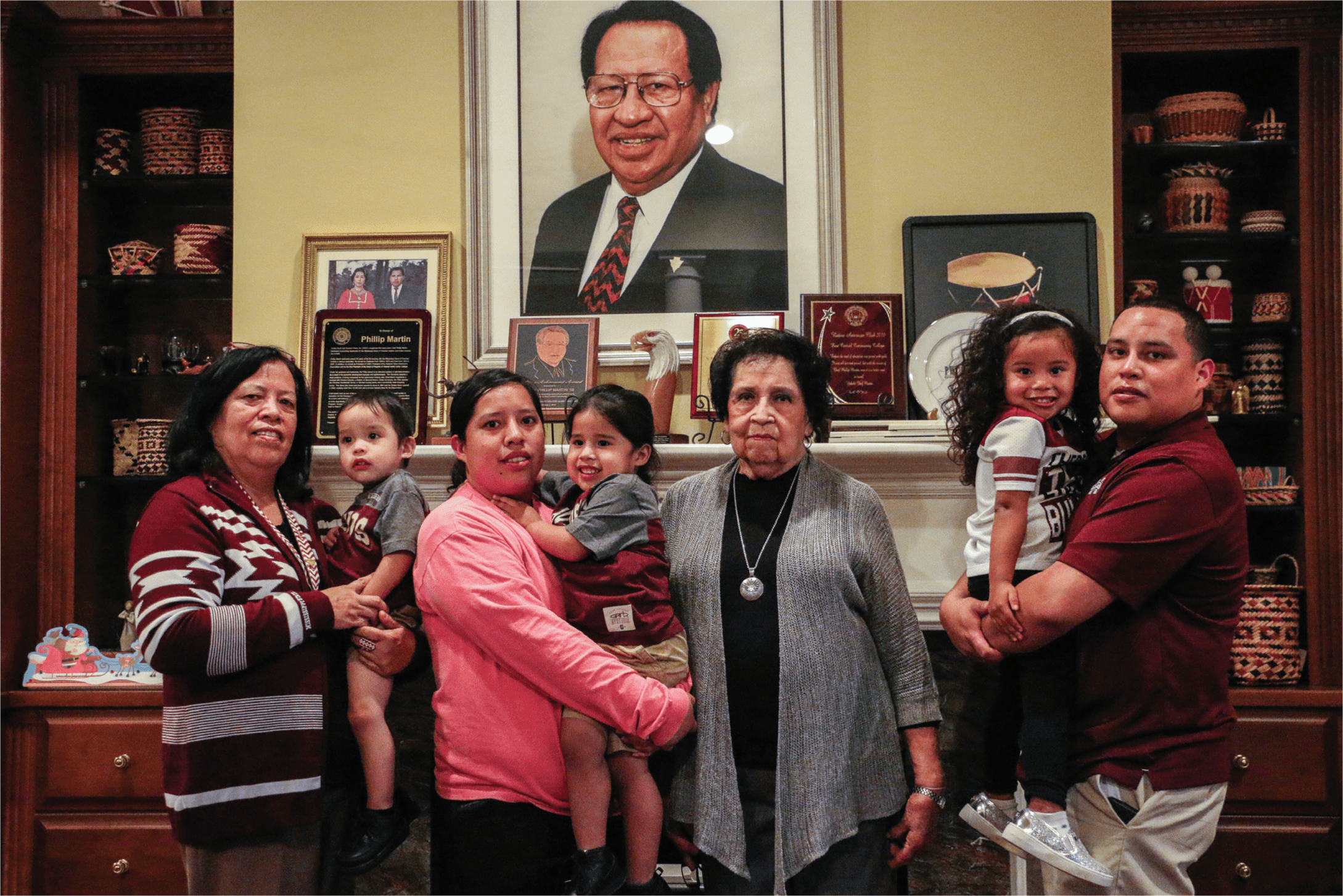

From left, Martin’s daughter Debra Martin, great grandson Hazzen Thomas, granddaughter Winter Lewis, great grandson

A’Mi Clemmons, Martin’s wife Bonnie Martin, great granddaughter Paeton Gibson and grandson Nigel Gibson. Photo by Chi Kalu

“He got that the tribe’s relationship was not with the state government. The tribe’s relationship was with the U.S. Congress. He really believed in what he called being a ‘good neighbor,’ but what he was really talking about was how you build collaborative relationships. He made a lot of allies.”

In 1981, Martin managed to bring home what was certainly the biggest win of the century for the Choctaw. After years of extensive travel and lobbying manufacturers across the country, Martin managed to persuade American Greetings, today the largest producer of greeting cards in the world, to open a manufacturing plant on the reservation.

More industry and hundreds of jobs would follow. Everything from plastics molding, to a printing facility and construction enterprises, would eventually make their way to the reservation.

According to the tribe’s director of economic development, John Hendrix, Martin had no qualms about confronting the nation’s captains of industry. He seemed to know no fear.

“He would go to a McDonald’s convention, when we were a supplier for plastics, and he would walk up to the CEO of McDonald’s and say, ‘We want to supply forks,’” Hendrix said.

“Not many people can do that. It was part personality, part leadership style, and then his hands-off management approach.”

Chief Martin, shown here with the late U. S. Senator John

Stennis, D-Miss., developed plenty of powerful allies in the

nation’s capital.

In 1994, the Silver Star Casino, what would become the crown jewel, the cash cow of the Choctaw reservation, opened its doors. It was followed by the adjacent Golden Moon Casino in 2002, and by two world-class golf courses and later the Geyser Falls Water Theme Park. Today, these establishments employ several thousand people, the majority of whom are tribal members.

There are now some 200 Native American tribes who participate in the casino industry in one form or another. Many take portions of the multi-million-dollar profits and divide them among tribal members, sometimes amounting to several thousand dollars a month. Martin however, disagreed with this practice.

Before the Choctaws’ first casino was built, he would enter into an agreement with the state of Mississippi, stating that no more than $1,000 of per capita distribution would ever be given as a stipend to Choctaw tribal members.

“He felt like they could get a little bonus out of it, but it shouldn’t be enough to let them not have to go and do their own thing. He created an environment where he created opportunity, and it was up to the tribal members to pursue it,” Hendrix said.

In the end, it turned the Choctaw into one of Mississippi’s biggest employers, a tribe that not only provides its members with a vast array of services including everything from medical care to food programs for the elderly, but that also boosts the economy of a wide swath of east-central Mississippi, a region that has historically needed every bit of help it could get.

Martin’s evangelical brand of self-reliance transformed the Choctaw into a smoothly humming economic engine, a powerful lobby in Washington, D.C., and a reputation as one of the nation’s most successful tribes.

Martin served as chief for almost 30 years before being defeated by Beasley Denson in a bid for an eighth term in 2007. When Martin died of a stroke in 2010, The New York Times ran a glowing obituary eulogizing him as the forerunner of Indian resurrection, a prophet of self-reliance who inspired other tribes to pick themselves up from the ruins of the past and build prosperous new nations, just like the Germans. Congressmen and state officials flocked to his funeral.

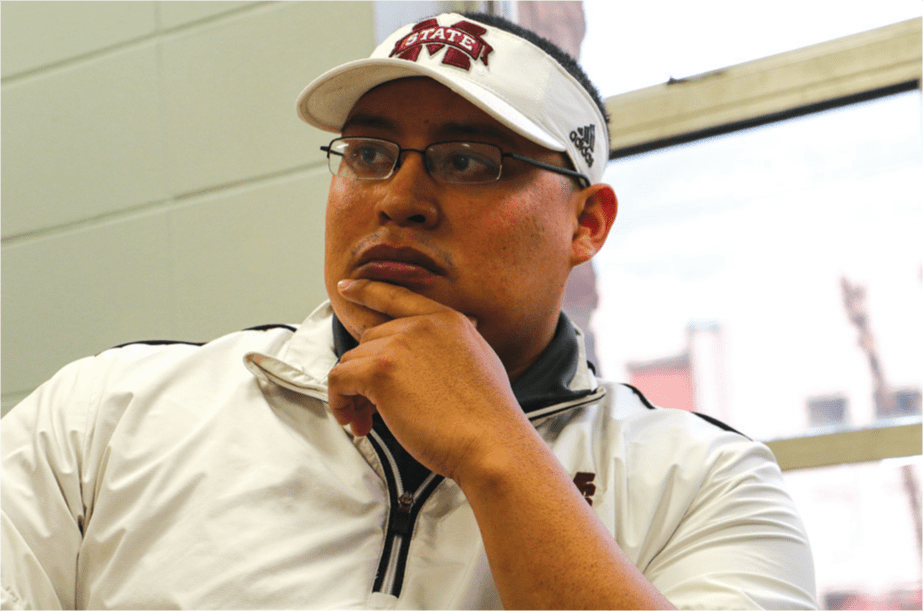

The chief’s grandson, 25-year-old Nigel Gibson, is the epitome of the effect that mindset of hard work has had on the youngest generations of Choctaw. A political science major at Mississippi State University, this man dressed in college athletic wear, with plans to become a lobbyist in Washington, is a far cry from the humble parameters that once defined the tribe.

Gibson describes Martin carefully, creating a portrait of a loving grandfather who in many ways was still ultimately a businessman, even in the familial aspects of his life.

“I was probably 15 or 16 at the time and I did something where I needed a little help financially. I went to him, and of course him being the businessman that he was, it was always ‘Well, what’s the cost? Who is doing what? Have you got a second opinion?’ That type of deal,” said Gibson.

“This particular time he called, he went to the casino around maybe 10 o’clock in the morning, and that’s where he would always eat in the buffet. We were sitting there and he made it seem like I was some sort of businessman. I meet him over there and of course he pulls out an envelope under the table. I thought, ‘Really? We have to do this here, in front of everybody? We could have done this at your house!’”

“That’s the kind of games he would play with us,” Gibson mused. “I would play around with him too, like call him ‘Chief’ and all that stuff. But he would make it known that ‘You don’t call me that, you call me Papa. I may be Chief to them, but I’m your Papa.’ That’s the kind of love he gave us in that sense.”

Phillip Martin’s grandson Nigel Gibson, a political science major at Mississippi State University, hopes to become a Washington lobbyist. Photo by Chi Kalu

Phillip Martin’s wife of 55 years, Bonnie, still mourns her husband, who passed away six years ago at the age of 86.

“It’s hard for me to talk about him. I get too emotional when I think about him. People had wanted me to interview with them since he passed away. I just can’t. Just talking about him to someone … These questions that they ask. Can’t stand it,” she said.

The inside of her home, the one Martin built for her, stands in tribute to his legacy better than any quote could. His pictures, awards, and trinkets, all slowly fading memories of a better time, line the living room walls. While she stands firm in her unwillingness to answer direct questions, she cannot seem to help the stray comment that escapes her lips every now and again, small, fond musings on vacations, dinners, moments long past.

“I was always amazed when he tells me that he’s going to do this,” she said, with a smile that did not reach her eyes. “I didn’t believe him at the time. But I saw the end result.”

To enter the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians reservation today is to enter a whole other world. It is a small city, characterized by the opulence of its casinos, hotels, and brand-new health and justice complexes, casting shadows on the small low-income housing projects among the modern subdivisions springing up in the pines.

Ask any tribal member about Martin, and they will tell you a story. Stories of pain, loss, and struggle that all end with one theme: redemption. The fondness for a father lost is obvious in the voices of his people.

Phillip Martin has been described as a modern-day Moses, a comparison that the testimonies of many Choctaw led out of their proverbial Egypt attest to.

“One thing I do know,” said Nigel Gibson proudly, “is that it’s never just Phillip Martin. It’s always ‘Chief.’ We only have one chief, and he carries that name.”

By Victoria Hosey

LEFT TO RIGHT: Ariel Cobbert, Mrudvi Bakshi, Taylor Bennett, Lana Ferguson, SECOND ROW: Tori Olker, Josie Slaughter, Kate Harris, Zoe McDonald, Anna McCollum,

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw and Choctaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.