Headlines

Unconquered and Unconquerable: The Forward Thinker

Piominko became friends with George Washington, protected the settlers of Nashville and sounded like Martin Luther King Jr

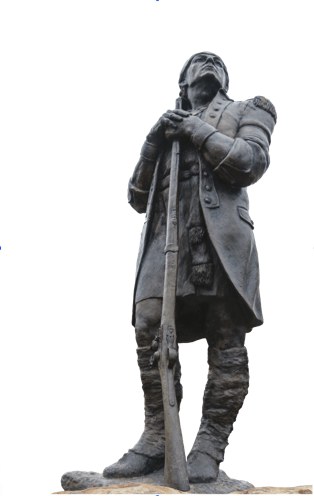

Sculptor Bill Beckwith’s Piominko statue graces the front lawn of Tupelo’s City Hall, across from a sculpture of Elvis Presley, the town’s other famous son.

The front yard of Tupelo’s City Hall proudly sports homages to the town’s two most revered heroes, men who could not be more different – rock ‘n’ roll king Elvis Presley and Chickasaw Chief Piominko.

The average visitor may wonder just how a short- statured Chickasaw man rose to the same level of celebrity as the King of Rock n’ Roll himself. After all, Piominko lived more than 200 years ago, a time when news coverage was sketchy at best, while Elvis’s every move was dissected daily by an adoring media.

Without Piominko however, this country and the Chickasaw Nation could be very different places today. He led the tribe through one of the most tumultuous periods in its history, as well as assisting a fledgling America when the country’s viability was still an open question. He helped protect the settlers who built Nashville, negotiated a treaty that established boundaries for the tribe’s lands, helped prevent Spanish influence in the new world from growing stronger and became a friend and battlefield ally of George Washington.

Unlike some chiefs, power was not placed in his lap because of birth or wealth. He rose through the ranks, a reminder that a man can become extraordinary by his actions alone. Historians describe Piominko as standing for morality and perseverance, and over the years this has gained him many fans.

George Washington was one of these fans, and he was a big one. He valued Piominko’s advice and friendship as much or more than any other American leader had previously valued a Native American. Washington had Piominko visit him and stay in his own home, an act unprecedented in American political leadership.

“[Piominko] appealed to people’s good and altruistic intentions. He was genuine in his dealing, loyal to his allies, and fierce to his enemies,” said Chickasaw archaeologist Brad Lieb, who is collaborating with historian Mitch Caver on a book about the chief.

As Lieb tells it, Piominko had the charisma needed to be popular but also mastered the skill of leading while listening. He could talk so well that people overlooked his less than commanding stature and atypical appearance. He was small and pale compared to most Chickasaws, but he made up for it with tenacity.

Piominko was born around 1750 in the Chickasaws’ main settlement of Old Town near modern-day Tupelo. Lieb said the chief’s mother was said to have been a refugee from another tribe but his father was Chickasaw. He first gained status through his battlefield exploits, earning more respect as he climbed upward through the ranks, even spending some time among the neighboring Cherokees.

Chickasaw from Oklahoma on a tour of the tribe’s homeland stop to examine a statue of Poiminko in downtown Tupelo.

In 1786, he negotiated the Treaty of Hopewell with the United States, winning the respect of the new nation’s negotiators. The treaty effectively recognized the Chickasaws as a nation, and established its boundaries. Piominko and the U.S. government agreed on 11 points, most of which reaffirmed Chickasaw control over their own land. At least theoretically, they could now punish American settlers if they trespassed. The 11th term listed was a promise of “peace and friendship perpetual.”

Piominko’s success in protecting Chickasaw sovereignty during the Hopewell negotiations brought him more attention as he continued to show skill on the battlefield. The Spanish were allying with rival tribes and Piominko knew his people would need help if it came to war.

He and what Lieb described as a “motley crew of Chickasaws, some wearing tailored suits and some shirtless, bearing their war tattoos” traveled to Philadelphia to visit President Washington in 1794. A young secretary named John Quincy Adams documented the visit. Both sides were nervous, but the Chickasaws called President George Washington “father” and they all smoked a pipe together to establish kinship.

Washington granted Piominko’s request for American help in pushing back the encroaching Spanish alliance with the Muskogee Creeks in the South.

In 1795, Piominko weathered an internal power struggle involving Spanish encroachment on Chickasaw land along the Mississippi River. Another Chickasaw minko (chief) named Wolf’s Friend was wary of the growing friendship between his tribe and the Americans. He saw the friendship of the U.S. as “the caress of the rattlesnake around the squirrel, before consuming him,” said Lieb. He gave the Spanish permission to set up a fort on the Chickasaw Bluffs at present-day Memphis on the Mississippi River.

When Piominko found out, he immediately led a band of warriors to the river, where they stood the Spanish down.

His leadership became critical when American Gen. James Robertson came over the Appalachians into Indian Country to found a settlement that would become the city of Nashville. These settlers were the first to successfully hop the Appalachians from the old colonial settlements in the East, and were unprepared for the constant attacks from disruptive tribes.

Piominko and the Chickasaws protected the settlers as they established their community along the Cumberland River. Eventually, Robertson became a federal representative to the natives. Lieb said Piominko’s “relationship as the savior of the founders and settlers of Nashville” was useful in later negotiations. Piominko reunited a fractured Chickasaw government and redefined the role of chief as a military leader and ambassador to the United States. Washington awarded him the Presidential Peace Medal for his constant assistance. The two great leaders died in the same year, 1799. Washington’s grave is protected and revered, but Piominko’s is unmarked, and not even in the tribe’s possession.

The Chickasaws believe Piominko’s grave lies in the yard of a Tupelo home, where a developer once unearthed tribal artifacts. The artifacts are now believed to be in the hands of a collector in Canada. The tribe would love to one day have these back, and also to properly mark his grave.

Tupelo’s Rotary Club erected the city’s Piominko statue, sculpted by noted Mississippi artist Bill Beckwith of Taylor, in 2005. It shows the chief in a Washington-style military coat with the oval Washington peace medal around his neck. An inscription at the base quotes Piominko as saying, “Could I once see the day that whites and reds were all friends it would be like getting new eye-sight.”

“Piominko dreamed of a time when ‘red and white children’ could live together, which is very reminiscent of what Martin Luther King said much later in the 1960s,” said Lieb. “He was certainly a forward thinker; he paved the way for other leaders in both geopolitics and civil and human rights.”

Piominko had a vision for a progressive and budding Chickasaw nation, and fought to make it real. He remained humble until his death. According to Lieb, Piominko recognized the important role of Western-style education, even asking the President to provide higher education for his daughter. As minko, he never took pay and never became a wealthy man. He did not believe in good luck, but rather thought that men benefited from being pure spiritually and in their intentions, he said.

Without Piominko, the Chickasaw might not have stayed afloat so long in the seemingly inexhaustible flood of white settlers. Just as important, America’s founding might well been much bloodier.

By Slade Rand. Photography by Ariel Cobbert.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Ariel Cobbert, Mrudvi Bakshi, Taylor Bennett, Lana Ferguson, SECOND ROW: Tori Olker, Josie Slaughter, Kate Harris, Zoe McDonald, Anna McCollum,

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…