Headlines

Unconquered and Unconquerable: That Old House

The wooden front doors in the oldest part of Doherty’s house, located on the site of an old Chickasaw Council House. Photography by Ariel Cobbert.

On the western edge of Tupelo sits an inconspicuous Greek revival home shaded by an arc of grandfatherly cedars. Behind it is a spring, a pond, and a wide, rolling pasture dotted by black cattle.

But it’s what you don’t see that has fed Raymond Doherty’s obsession for decades now. For beneath the house and the thick, green grass lie clues to a history as rich as the soil that gave birth to Mississippi’s sprawling cotton kingdom.

The people who zip past on West Main Street have no idea what went on there, where George “Ittioltimastubbe” Colbert, a Chickasaw head man, lived and maintained a tribal council house. They would never know that Andrew Jackson slept here and an important treaty was signed here. They would never know it was used as a Civil War hospital, that a meteorite was found in the back yard, or, as some say, that it is now the home of a ghost.

Doherty hurries to a halt in a bright blue truck with a New York license plate. He is lanky stepping onto his driveway, with white hair that falls in his face and clunky, black glasses. When he speaks it is not with a slow, Mississippi drawl. Those childhood summers

he spent there were never enough to do that to him.

Doherty’s grandfather was from Monroe County; his grandmother from Lee. In 1953, the couple bought a rundown house on West Main and restored it. Doherty spent summers there, where his grandfather took him to find nutting stones in a freshly plowed field behind the house. The stones, of which Doherty now has a large inventory, were used four to eight thousand years ago, he said, to hold a nut in place while another stone cracked it.

“These are older than the pyramids,” Doherty said, picking one up. His eyes twinkle.

But it’s not these ancient stones that have fed Doherty’s 20-plus-year infatuation. It’s the other things — both tangible and intangible — linking his home to a wealth of Chickasaw history in which the Ole Miss graduate student has eagerly submerged himself. It has become the subject of his master’s thesis, besides.

By digging into old family lore, Doherty changed his life. He entered graduate school in Anthropology at age 60 and wound up unearthing revolutionary discoveries in Chickasaw ethnohistorical archaeology.

He and his aunt inherited the house when Doherty’s grandmother died in 1988. Since then, by digging through maps, letters and dirt, Doherty has discovered (among many other things) that his house sits on the site of a Chickasaw home built in 1814 by a man named George Colbert.

According to Robbie Ethridge, professor of anthropology at the University of Mississippi and author of a book on the Chickasaws, Colbert was the son of a Scottish trader who settled among the Chickasaws and married into the tribe.

“Getting married was one way to form kin relations,” she said. “You married into your wife’s family, so now you had her family, and they provided you protection if you needed it, alliances and so forth. It was a practical thing to do.”

Children of a Chickasaw and a European would have been called a derogatory term, “mixed blood,” according to Ethridge. But it was these children with a foot in both worlds who often rose to the top.

“They had intimate connections with the Indian groups through their mother’s family and because they were Indian, and yet they had these vast connections with the Euro-American world as well,” Ethridge said.

Raymond Doherty in front of his Tupelo house. When he started researching its past, the things he found helped change Chickasaw history. Photography by Ariel Cobbert.

These advantages and the matrilineal society of the Chickasaw paved the way for Colbert’s leadership. He became a head man, a town leader who answered to a tribal council. This was common practice for the time, according to Ethridge, rather than having a single chief or governor as most tribes do today.

But although he was one of many leaders, Colbert had immense influence.

“Those Colberts became real good capitalists,” Ethridge said. “They were running ferries and they were running inns. They had a lot of businesses, so economically they started to gain some wealth. They were also great entrepreneurs.”

Doherty knew a lot of this, but when he uncovered the original foundation of Colbert’s home peeking out from under the front of his house, it was a eureka moment.

There have been many of those along Doherty’s journey of detective work. Rabbit holes and dead ends and crazy, unexplainable things have kept him interested in the house for decades now.

For example, he discovered that his driveway was part of the original Natchez Trace. And, perhaps most amazingly, that Andrew Jackson once stayed at Colbert’s house for three weeks.

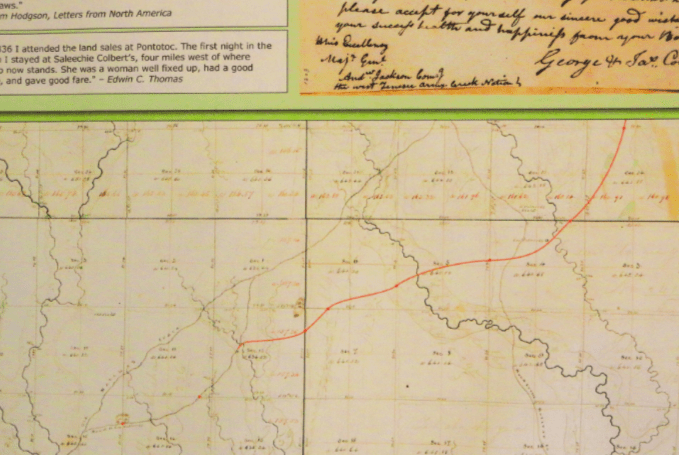

It all started with a piece of paper in the Library of Congress.

“A letter was found when I was first doing the research, 30 years ago, and it’s a letter from George Colbert to Andrew Jackson, and it’s dated Chickasaw Nation, 10th of January, 1814,” Doherty said.

According to Doherty, Colbert had been living at a ferry he operated on the Tennessee River during that time.

“The question was when did he move back here and why?” Doherty said.

Doherty’s has collected old maps and letters relating to the house and its history.

The letter answered that question. He had moved to Tupelo and established the national council house – whose foundation lies under Doherty’s house – in 1814, “and not 1818, which is when people thought. That meant the 1816 council that happened here with Andrew Jackson – and the treaty – didn’t get negotiated and signed up there, it got negotiated and

signed here. I was like, ‘This is fantastic.’ This letter is really unbelievable, and it’s kind of shocking, too.”

In a sense, Doherty had just rewritten history.

Eventually, this scrap of information led Doherty to the conclusion that the tribal house, whose foundation his current home sits on, was the site of a three-week conference Jackson convened with the Chickasaws and other Southeastern tribes.

“All the Choctaw chiefs came, all the Cherokee chiefs came,” Doherty said. “The Creeks then at the last minute sent a runner and said they weren’t coming, and for three weeks, they held a conference here where they deposed the leaders of the different tribes as to their histories and boundaries.”

Jackson wanted to acquire Tennessee for the U.S. government as part of a strategic goal to secure the Mississippi Valley established by Thomas Jefferson around the time of the Louisiana Purchase. The general, according to Doherty, was hoping to take advantage of disagreement among tribal leaders so that his buying the land would feel like some sort of solution.

Doherty recently got his hands on over 80 pages of transcripts of those depositions and related official correspondence from the Library of Congress.

“The chiefs start testifying as to their origins — not really why they claim this bit of land, but how they came there originally, which is huge,” he said. “Andrew Jackson would interrupt them and ask them a question. It’s like some congressional hearing. We only found this a few weeks ago.”

Through all of Jackson’s poking and prodding about land and fighting the Creek Indians, who were resisting European settlers’ encroachment, Colbert remained in control.

“Overall, I think the Colberts were masterful in keeping Andrew Jackson at bay,” Doherty said.

It had been a particularly tense time for the Chickasaw. A Red Stick Creek attack on Fort Mims spread terror throughout the Missisippi Territory and the nation. Jackson mobilized an army to crush the Red Sticks once and for all. In the midst of it all, a murder on the Natchez Trace in 1813 was blamed on the Chickasaws.

Clearly worried about retaliation, the Chickasaws wrote Tennessee Gov. Willie Blount to deny they were responsible. They also announced they were moving everyone to the center of the Chickasaw Nation into a defensive position. Determined not to be blamed, George Colbert wrote Jackson saying they had recovered the war club used in the murder and would find and destroy the Red Stick village it came from. Colbert became war chief, left his ferry and moved to this site near present-day Tupelo to build his home, which also served as the national council house.

Ethridge credits Colbert for keeping his tribe united during that time.

“This is early 19th century when the Chickasaws are up against the wall in terms of getting pressure for land and removal starting to rumble,” she said. “People are starting to talk about removal. Colbert and his leadership and the leadership that was in place at that time were instrumental in keeping them together and managing to retain their sovereignty in the face of just insurmountable pressure and odds.”

Knowing where Colbert lived but also to have the site available for archaeological research is both rare and valuable, said Ethridge.

“We know so little about Indian people, and we can rarely name their leaders, much less identify where they lived,” she said. “This is really unusual and it’s really important for that reason.”

So important that today, Chickasaws regularly come from Oklahoma to see Doherty’s house. It’s that significance that keeps Doherty going, although he’s accepted that his thesis won’t be finished on time. After all, the clues keep coming.

“The artifacts, the archaeology part of my thesis, the history part, is what’s really amazing,” he said.

Doherty should have been an archaeologist from the get-go. When he was a teenager, he attended Mississippi State University’s summer field school and was asked to return as a supervisor the next year. He was just 14.

But he didn’t answer the call. He considered law school and was living in Tupelo when he was first captured by the history of his grandparents’ home. But then, after his grandmother died, Doherty gave it up and moved to New York, where he worked for LEGO. He developed the LEGO Film School which supported the LEGO and Steven Spielberg Moviemaker Set.

“Things worked out well career-wise, but when I was down here, I was like, ‘Oh my God, what am I going to do with my life?’” Doherty said. “And so I just sort of got into this in an obsessed way.”

And he did it well. His research reveals how one Chickasaw leader, Colbert, stood up to Andrew Jackson and the full weight of the U.S. government right there in Tupelo and how he managed to at least temporarily preserve the Chickasaw homeland as well as the tribe’s sovereignty.

Some of the items Doherty has found on his rich-in-history property.

He credits much of the findings to Brad Lieb, the Chickasaw Nation’s Tribal Archaeologist, and his uncle, retired Alabama Museum of Natural History archaeologist John Lieb. According to Doherty, nothing happened until the uncle-nephew team showed up and said, “Let’s start digging.”

Using the dig and his document research and help from Tony Turnbow, executive director of the Natchez Trace Parkway Association, Doherty has managed to weave together a narrative of the site.

The original house was built in 1814 and occupied by Colbert. In 1816 the three-week council was held during which Jackson negotiated the purchase of Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi lands with chiefs from three Southeastern tribes. After the 1816 Treaty of the Chickasaw Council House and anothertreaty negotiated by Jackson two years later, the tribe

owned no land in Tennessee.

The incessant drumbeat of land demands from the U.S. government eventually led to the Indian Removal Act signed by Jackson, now the president, in 1830. Reluctantly, the Chickasaws eventually agreed to give up their remaining land in Mississippi and headed down the “Trail of Tears” for Indian Territory in what would later become Oklahoma.

White settlers named Walker moved into the Colbert home, and in the 1850s they built the existing structure on top of the old foundation, using the original Chickasaw period timbers. They were not as precise as the Chickasaws, however. The original home was built to face exactly east, whereas the new one is six degrees off, according to Doherty.

The east-facing quality is a classic Chickasaw signature. It is also at least possible that the semi- circle of cedar trees in the front yard was once part of a circle of cedars surrounding the old council house. One may be the oldest cedar in North Mississippi, still guarding the yard with all the authority that comes from being 300 years on this earth.

But there are still unanswered questions. For example, Doherty and the Liebs have found bits of pottery on the site that are inconsistent with Chickasaw methods.

According to Doherty, almost half the pottery they have found is made with grog temper, which meansthat it was made of tiny bits of old, broken pots instead of sand or shell. This “recipe” for pottery- making was utilized by the Natchez Indians, not the Chickasaw. And Doherty is stumped as to why they are finding it.

Brad Lieb agreed the pottery is “unanticipated” for the early 19th century. It indicates “connections with the mysterious and once-powerful Natchez tribe, as well as other far-flung associations that probably reflect George and Saleechie Colbert’s wide network of elite connections and traditional power bases among the Chickasaws, and the ceremonial gathering function of the Council House,” he said.

“Many more answers to as yet unasked questions still reside in the soil under the thick lawn at the site.”

There are other mysteries here, like the ghost.

According to Doherty, it lives in the front formal room, which sits atop the old foundation.

This photo shows the house the way it used to look.

“I’m a scientist, I really am. I don’t believe just anything, but this room is haunted,” he said. “Noises happen in here that one would describe to be haunted. It sounds like somebody’s in here walking around and moving around and knocking about. I got used to it, and it would wake me up in the night and I would just get on my computer, and it would go on for a couple hours until dawn.”

Doherty wonders if it is the work of a Chickasaw warrior who died in the Creek War. Once, a pair of Chickasaw women entered the room during a tribal tour and spotted what they took to be an image of a Chickasaw warrior formed by soot and ash on the bricks of the fireplace.

Doherty thinks he has some clues as to ghost’s identity. Among many of the metal objects found on the property was a part from an eighteenth century flintlock pistol and a large, deeply buried scalping knife.

“They don’t use pistols for hunting, they use them for killing people,” Doherty said. “A traveler on the Natchez Trace reported that he was told George Colbert was ‘in the habit of killing people.’”

Or, the ghost could be the spirit of a Civil War soldier. Both armies used the house as a hospital during the Battle of Tupelo, after all. The original pine floorboards are soaked in the blood of wounded Rebels and Yankees.

“In the 1930s, on a humid day you could wipe something on the floor and still get blood,” said Doherty, who wants to rip up the wall-to-wall carpet and restore those boards.

He also plans to restore the front porch and excavate underneath the house come fall. And if the findings continue to surprise him as they’ve done all these years, Doherty will likely discover something bizarre and puzzling. Like the brick stamped with the print of a dog’s paw. Or like the mysterious meteorite a friend unearthed that’s now in the New York Museum of Natural History.

But already, his findings have added to the narrative of Chickasaw history in Tupelo. And that, as much as anything else, is what Doherty’s home offers to both Indians and non-Indians alike.

By Anna McCollum. Photography by Ariel Cobbert.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Ariel Cobbert, Mrudvi Bakshi, Taylor Bennett, Lana Ferguson, SECOND ROW: Tori Olker, Josie Slaughter, Kate Harris, Zoe McDonald, Anna McCollum,

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies will be available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…