Arts & Entertainment

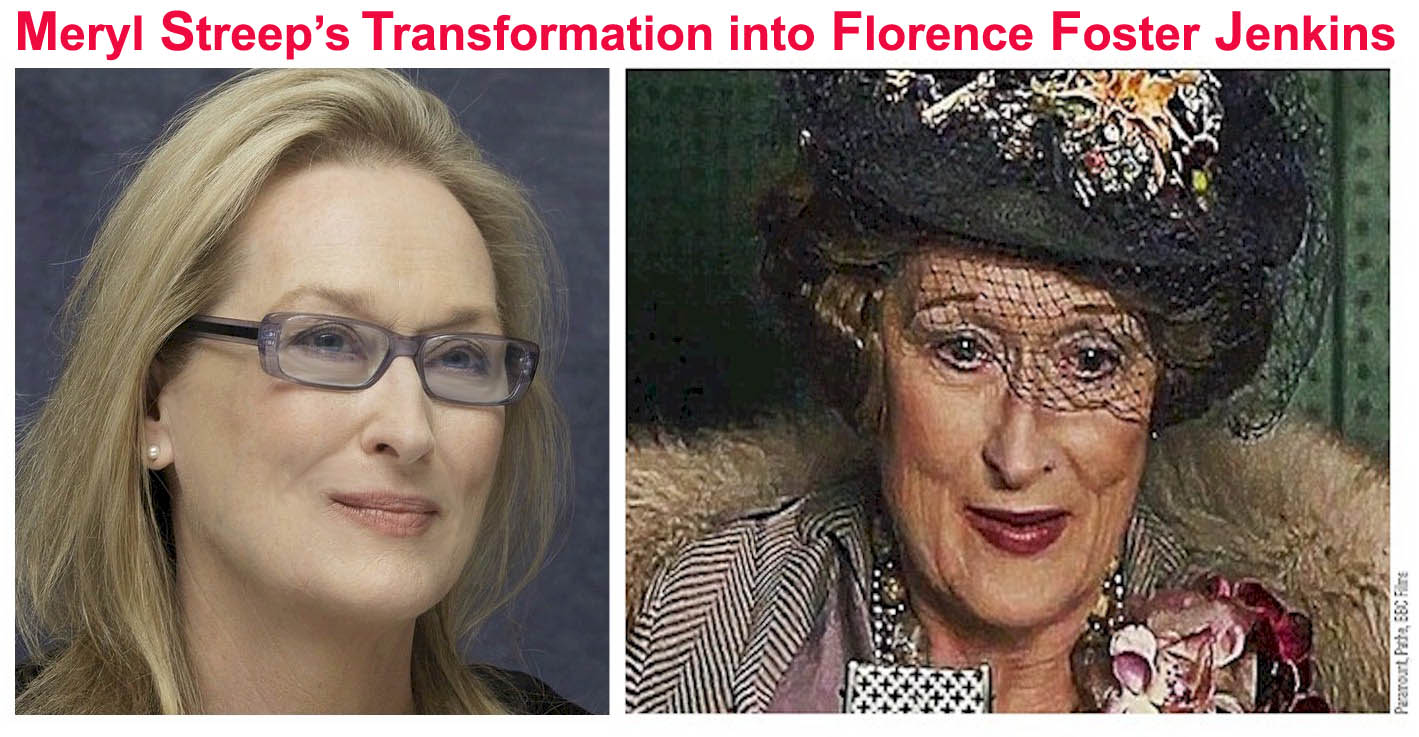

Meryl Streep’s Transformation into the World’s Worst Singer, Plans to Return to Theater

Ellis Nassour is an Ole Miss alum and noted arts journalist and author who recently donated an ever-growing exhibition of performing arts history to the University of Mississippi. He is the author of the best-selling Patsy Cline biography, Honky Tonk Angel, as well as the hit musical revue, Always, Patsy Cline.

For almost 40 years, Meryl Streep has portrayed an astonishing array of characters in a career that, sadly, cut short her theatrical ambitions but blazed a path of incredible artistry in film.

For almost 40 years, Meryl Streep has portrayed an astonishing array of characters in a career that, sadly, cut short her theatrical ambitions but blazed a path of incredible artistry in film.

Many consider her “the greatest living actress.” She’s won three Oscars from 19 nominations [the most of any actor/actress]. There’ve been 28 Golden Globe nods with eight wins, and two Emmys.

Streep’s living proof that there are roles for women not only over 40 but also over – well, we won’t go there. In appearances for the film, dressed casually with her hair often in a pony tail and even while wearing her tinted glasses, she seems to have found the fountain of youth. In the About Time category, she’s considering a return to the stage.

“I’d like to do something onstage,” she states, “but I don’t want to do a revival. I want to do something new. So I’m looking around!”

Terrance McNally are you listening? Since she’s in pre-production for Disney’s Mary Poppins Returns, directed by Oscar nominee Rob Marshall (Chicago, film), with a score by Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman (Hairspray). It’s set for release in 2018, so there may be a long wait.

After Ricki and the Flash and what amounted to a cameo in Suffragette, Streep’s as engaging as ever in her return to serious film roles in the biopic Florence Foster Jenkins (Paramount/Pathe/BBC Films) as the headstrong New York socialite who lived for music and had a burning obsession to sing.

FFJ’s spirit was willing, but the vocal chords weren’t.

“What attracted me,” states Streep, “was what propelled her in the face of adversity, what kept her going.”

The actress claims she can’t sing well, but she’s well trained. Before she opted for an acting career, she desired to be an opera singer. But onstage and onscreen, she began signing early on.

At unique time in history for women, the aptly-named Narcissa Florence Foster, was a 1930s New York socialite who exuberantly pursued her dream of becoming an opera diva until her death in 1944 at 76. Her vocal output was politely described as “swoops and hoots, wild wallowing in descending trills and repeated staccato notes that were like a cuckoo in its cups.”

FFJ became the darling of the superrich who participated in a great deception because of her philanthropy – made possible by personal wealth and that which her late millionaire husband bequeathed. The Number One culprit was her common-law husband, a not-so- highly regarded British Shakespearean actor, St. Clair Bayfield, her protector and manager, beautifully and subtly played by Hugh Grant. It was smooth sailing and friendly deaf ears until Jenkins’ maniacal decision to rent Carnegie Hall and debut her tunelessness to the masses.

FFJ became the darling of the superrich who participated in a great deception because of her philanthropy – made possible by personal wealth and that which her late millionaire husband bequeathed. The Number One culprit was her common-law husband, a not-so- highly regarded British Shakespearean actor, St. Clair Bayfield, her protector and manager, beautifully and subtly played by Hugh Grant. It was smooth sailing and friendly deaf ears until Jenkins’ maniacal decision to rent Carnegie Hall and debut her tunelessness to the masses.

Streep says what could have been just a laugh-out-loud comedy “under [director] Stephen [Frears] and Nicholas Martin’s screen treatment became a poignant, smart, and charm-filled tale of love that transcends illusions and the never-ending allure to achieve impossible dreams. They took something that’s fundamentally hilarious and delved into the humanity of it. It depends on lightness—like that of a soufflé.

“What I loved is that the story has so much emotion,” she continues. “It’s not only about Florence’s enduring love of singing, no matter the realities, but also about a long and happy relationship between two who may have come together out of self-interest but are sustained by honest feeling and affection. The illusion is in how they prop up each other. It is the compromises that people make that makes life worth living.”

Streep is known to be a perfectionist and is meticulous and painstaking in preparation for role. When she received Martin’s screenplay, what riveted her and was how he approached Jenkins as a person. The role would present another opportunity to examine the gamut of human behavior and “the mysteries of the creative impulse, which can turn people into obsessives.”

She dug deep for fresh character exploration of the imperiousness of the grand dame and the tragically thwarted creative artist inside her.

“Calamitous singing aside,” she saw in Florence “a woman who was not only funny and vibrant but also powerful for her times. There weren’t that many opportunities women of privilege and education. Except for a very few, they weren’t in law, they weren’t in business. They found their ranking in society and in clubs.”

FJJ gave away huge amounts of money,” states Streep, “and was a great patron of the arts. Florence kept New York’s musical life alive underwriting concerts at Carnegie Hall, clubs, and salons, where she did lavishly-costumed recitals. It was how she moved up the echelons of society. She was silly and wore ridiculous clothes, but she was happy and enjoyed her life.”

Jenkins created all her own outfits and was inspired by the style of “a Mexican señorita” and 18th-century ball gowns among other things. She considered herself a supreme performer, and could afford to have clothes that were gorgeous – and gorgeously outrageous, and high camp. FJJ had no embarrassment, even being lowered from the flies in a pair of heavenly wings.

Streep pondered “why Florence insisted on singing when she had other ways of making an impact? I came to realize what makes her so interesting is how close she comes before her voice goes wildly off. She’s almost there. In Florence’s mind’s eye she was achieving it and that’s what must have kept her going.

“What’s heartbreaking — and heartbreakingly funny — is her aspiration,” she adds. “You hear her breathing, but in all the wrong places. She’s a little too late to hit notes, but you can hear the desire, her love of music, and how close she comes. I never wanted to make her a fool.”

Foregoing opera, acting attracted Streep while she was a Vassar and at the Yale School of Drama, where she had her introduction to Florence Foster Jenkins. “During a break in rehearsals, students from the School of Music were screaming and laughing and passing around a recording. Some of us actors asked ‘What’re you listening to?’ We heard all sorts of screeches. It was Florence!”

Such was the vocal world of FFJ that Streep had to undo everything she knew to capture that inimitable voice.

Score composer Alexandre Desplat says, “Meryl has a huge range. She understands music and has great feeling for it. What was striking was how she sang out of tune, which is very difficult. To pretend to sing badly you have to be a very strong musician. Meryl’s very precise. She did a remarkable job.”

Score composer Alexandre Desplat says, “Meryl has a huge range. She understands music and has great feeling for it. What was striking was how she sang out of tune, which is very difficult. To pretend to sing badly you have to be a very strong musician. Meryl’s very precise. She did a remarkable job.”

“I have a very clear understanding of what my voice is,” states Streep. “It’s a B voice. It hovers around B minor. I’ll never be a great singer. My family hates for me to sing at home! But singing through a character is something I know I can do. With Florence, it led me to understand her exuberant will to sing.”

Her biggest anxiety was that she couldn’t sing as high as FFJ did. “I thought it would be a piece of cake, but it was much more difficult. Florence tackled some of the most difficult arias in the canon of opera. She hit an F above high C. Do you know how high that is? It’s just insane.”

The way FFJ went wrong didn’t really have rhyme or reason to it, explains Streep. “Her biggest problem was that she forced her voice. The resulting pressure and tension in her carriage caused the sounds that would suddenly emanate from her mid-note.”

Her goal was never mimicry. “I wanted to make the role fully alive in the moment.” Screen writer Martin heard a clip “and was amazed how much she echoed Jenkins’ voice and how she’d captured her tragedy and hilarity.”

The vocals were pre-recorded, as is the case with musical numbers in film, and were to be played back on the set, in spite of the fact that it makes it difficult for the actors. Then, Frears changed his mind. “We did it all live,” she enthuses. “That made us very alive, because it changed each time. But we set ourselves up to fail big time. It was more terrifying, but way more fun.”

More arias were done for the Carnegie Hall sequence “that thankfully are not in the film,” but the captive audience heard them all.

Meryl Streep made her Broadway debut in the short-lived 1975 revival of Pinero’s Trelawny of the Wells for the NY Shakespeare Festival at the Beaumont. The next year, she appeared in a revival of two one-acts: Tennessee Williams’ 1955 27 Wagon Loads of Cotton as Flora, wife of a Mississippi cotton gin owner [in 1956, Elia Kazan took this three-character play into controversial territory in a greatly-expanded adaptation rechristened Baby Doll, starring Carroll Baker as Flora/Baby Doll], and Arthur Miller’s 1955 A Memory of Two Mondays.

In 1976, she was Drama Desk-nominated for the short-lived revival of William Gillette’s 1896 play, Secret Service, set against the Civil War. In early 1977, for NYSF, Streep was DD-nominated (Supporting) for her chambermaid Dunvasha in The Cherry Orchard, which starred Tony-nominated Irene Worth. That April, she made her Off Broadway singing debut as Hallelujah Lil in an English version revival of Weill-Brecht’s Happy End, for which she was DD-nominated (Actress). The play moved to Broadway, and she made her main stem singing debut.

For her title role in Elizabeth Swados’ Alice in Concert at the Public, she was honored with a 1981 Obie. To salute her work under Joe Papp at the Public, Summer 2006, Streep returned to her roots appearing in Central Park in a quasi-musical adaptation by Jeanine Tesori of Bercht’s Mother Courage and Her Children, directed by George C. Wolfe and starring opposite old friend Kevin Kline; and was DD-nominated (Actress).

In films, Streep’s actually trilled the light fantastic all the way back to Silkwood, Ironweed, and Postcards from the Edge.

She hadn’t set out for a film career until Robert De Niro’s performance in Taxi Driver had a profound impact on her. In 1975, Frederico De Laurentiss, son of Dino and executive producer of the King Kong remake, brought her in to audition. His father exclaimed, “Ciò è così brutto! Perchè mi avete portato questo? (This is so ugly! Why did you bring me this?). Streep understood Italian and bravely spoke up: “Mr. De Laurentiss, I’m sorry I’m not as beautiful as I should be but this is it. This is what you get.” Mr. DDL lived long enough to realize what he didn’t get!

Streep made her big screen debut in 1977’s Julia. Most of her scenes were cut except for a bit in a flashback. Of that experience, Streep said: “They took the words from the scene I shot with Jane Fonda and put them in my mouth for a different scene. I thought, I’ve made a terrible mistake. No more movies. I hate this business!” It was Fonda who convinced her otherwise. Streep credits her “for opening more doors than I probably even know about.”

In 1978, Streep won an Emmyfor the miniseries Holocaust, then came starring opposite De Niro in 1978’s The Deer Hunter, about the impact the Vietman War has on a Pennsylvania industrial town. It put Michael Cimino on the map, winning the Oscar for Best Picture; and gave Streep the first of her long roster of Oscar nominations (as Supporting Actress) [and a Best Actor nod for De Niro]. She was reunited with co-star John Cazale (The Godfather I and II, Dog Day Afternoon), a friend her Public days. They had an affair until his death from lung cancer shortly before the film’s release.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…