Featured

UM Workshop Helps Teachers Help Impoverished Students

By Clara Turnage

University of Mississippi

More than 75 educators from across Mississippi experienced one month in the life of an impoverished person last week as a part of the Missouri Community Action Network Poverty Simulation at the University of Mississippi.

The workshop, one of several free programs the UM School of Education is hosting this year as a part of its two-year Education Equity Initiative, was designed to educate Mississippi teachers about the hardships specific to students who live below the poverty level.

The U.S. Census Bureau in 2022 estimated that 19.4% of Mississippians – more than 560,000 – are living below the poverty line, defined as an individual earning less than $14,580 or less than $30,000 for a family of four.

“This is a simulation, not a game,” said Rebecca Cummins, Community Action Poverty Simulation project manager. “Poverty is not a game for 562,000 people in your state, including about 1 in 5 in Mississippi.”

What may seem like a reasonable ask for one student – such as $10 for a field trip – could alienate a student living in poverty, said Sara Platt, UM assistant professor of special education. The simulation is one way that the university is preparing teachers to better understand and support all students, she said.

“Research says many teachers teach like they were taught,” Platt said. “Many of our students training to become teachers have not attended public schools or schools where there are high numbers of students experiencing poverty.

“Our goal is to train our UM teacher candidates to become more aware of the issues and challenges experienced by families living in poverty.”

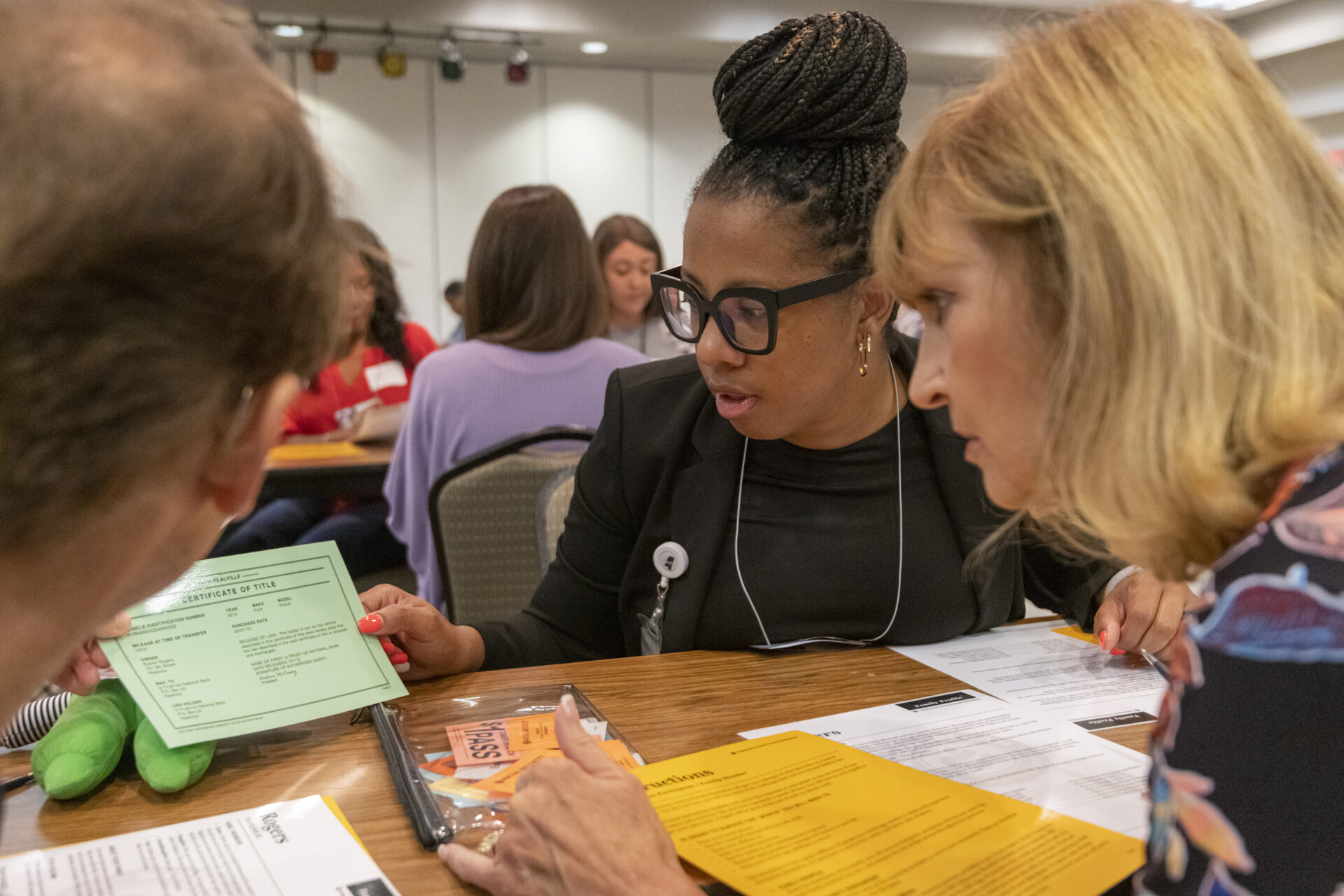

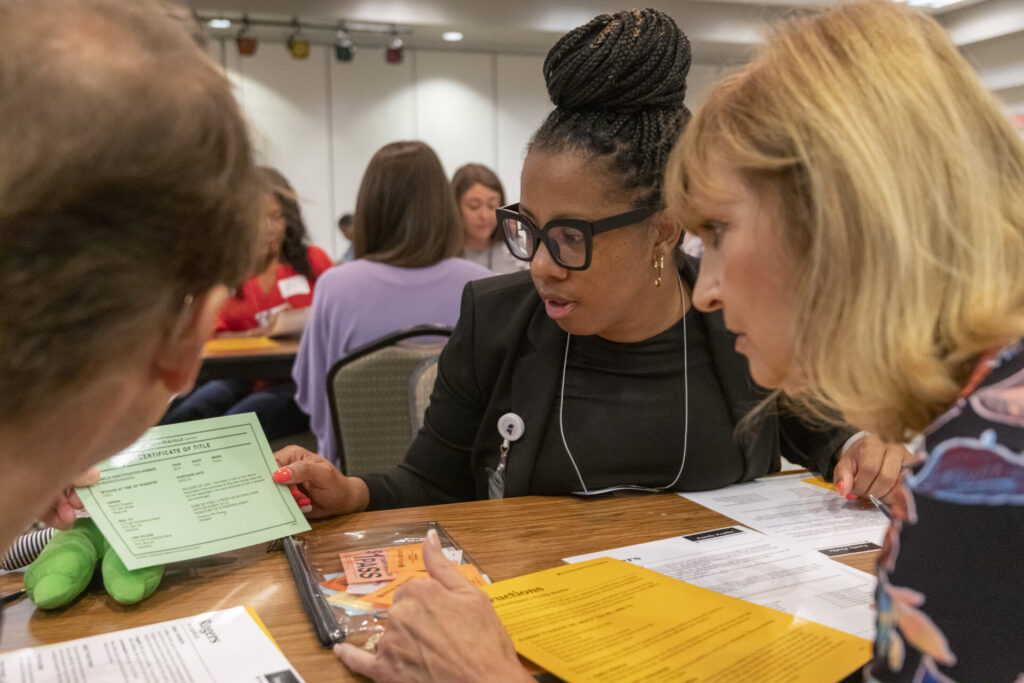

During the first day of the workshop, teachers from across Mississippi, Ole Miss faculty members, graduate students and representatives from the Mississippi Department of Education were assigned roles as members of families experiencing poverty and hardship.

Each family had a different set of challenges and circumstances to navigate throughout the program’s four 15-minute weeks, including limited wages and transportation, overdue bills, eviction notices and, in some cases, incarceration. While maintaining their households, participants were also responsible for sending their children to school each day and often found themselves faced with difficulties such as a sick or injured family member, loss of a job, homelessness and robbery.

At the end of the simulation, Megan Bania, executive director of the Missouri Community Action Network, asked the participants, “How many of you asked your children how they were doing in school? How many of you asked about their grades?”

None of the participants raised their hands.

“Coming from someone who has experienced poverty, this was amazing,” said Annette Matthews, a special education teacher in Okolona Elementary School. “We never know what our students are coming into class from. We never know what our students are going through.

“As teachers, we have to be mindful, even if you haven’t experienced what they have. Remember that most of us are one illness, one short paycheck away from being in a poverty situation.”

The goal was not only to increase empathy and understanding between teachers and students whose families are experiencing poverty, but to provide those teachers with resources to help students, Platt said.

“It’s not enough to understand what poverty is and does; teachers and community members must know how to help people living in poverty,” she said.

The second half of the workshop focused on identifying resources and ways to help students whose families are experiencing poverty and how to include poverty-sensitive training in the classroom.

The School of Education also purchased three Community Action Poverty Simulation kits with the goal of incorporating poverty awareness into its classrooms.

“Thinking from the perspective of educators, school is the only consistency these kids have,” said participant Lekeisha Sutton, a leadership coach with the Mississippi Department of Education’s Office of School Improvement. “How do we, as educators, ensure that school is their safe place? Because we don’t know what’s going on at home.”