By Taylor Vance

Mississippi Today

JACINTO — Candidates for the state’s highest offices were stumping under the historic Jacinto courthouse at the community’s annual Independence Day festival, but certain people in the area won’t have a say this year in which of those candidates represent them.

Mississippi is one of fewer than 10 states that places a lifetime voting ban on people convicted of certain felonies, resulting in more than 10% of the state’s voting-age population being barred from the ballot box, according to one study.

Numerous people from nearby communities in northeast Mississippi have petitioned state politicians in recent years to return their voting rights. But because of the state’s convoluted system for getting those rights restored, their efforts have been unsuccessful.

The U.S. Supreme Court last week declined to hear a case challenging Mississippi’s process for stripping voting rights from people with certain felony convictions, leaving the future of this system in the hands of state officials.

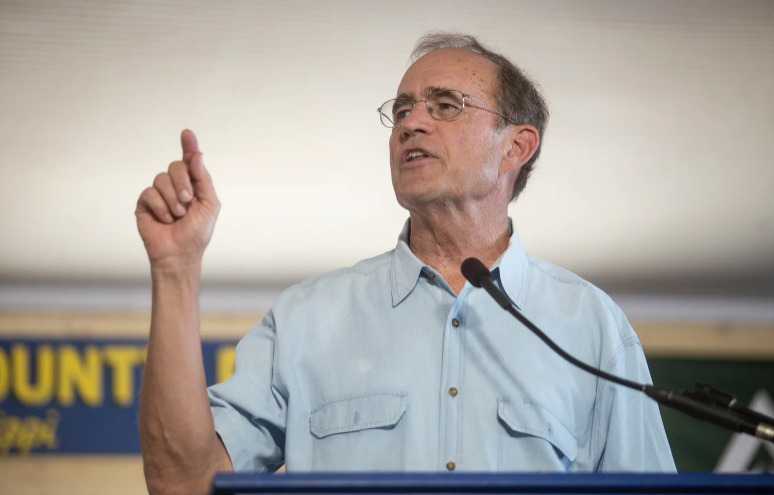

“I’m open to doing something,” Republican Rep. Nick Bain of Corinth told Mississippi Today. “But we frankly can’t do anything until we get the governor on board,” Bain said.

READ MORE: Supreme Court refuses to hear Mississippi felony suffrage appeal

Once a person has had their suffrage taken away from them, it’s incredibly difficult to get it back.

To do so, a disenfranchised person must get a lawmaker to sponsor a suffrage restoration bill on their behalf and get two-thirds of both the House and Senate to approve of the legislation. The Legislature did not approve of any suffrage restoration bill this year.

A governor can also pardon a convicted felon, but both Reeves and his predecessor, former Republican Gov. Phil Bryant, have declined to issue any pardons.

Reeves’ campaign did not make the governor available for questions from the press on Tuesday, but he has previously told reporters that he is hesitant to change the current disenfranchisement process.

Brandon Presley, Reeves’ Democratic opponent, said he wants to establish a criminal justice task force to examine felony suffrage and other measures but stopped short of calling for an overhaul of the system.

“I think there is a common sense approach to dealing with this issue, and it’s clear that when you go an entire year, and no one’s right to vote has been restored, that we’ve got a system that needs to be looked at,” Presley said.

While candidates debate whether the system should be revamped, the current process has real implications for a significant number of Mississippians.

More than 235,000 people in the state cannot vote because of a felony conviction, according to an estimate by the Sentencing Project, a criminal justice non-profit organization. Black people make up more than half of that disenfranchised population.

The lieutenant governor, who leads the Senate, has a direct impact on legislative policy. Incumbent Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann and his challenger, state Sen. Chris McDaniel of Jones County, are both competing in the Republican primary this year.

Both Hosemann and McDaniel told reporters on Tuesday they want to maintain the status quo and leave the system intact for the foreseeable future.

“I don’t approve of violent criminals,” Hosemann said. “If you’re a murderer and rapist, I’m not giving you your right to vote back. You’ve cut yourself out of society.”

The current structure stems from the framers of Mississippi’s 1890 Constitution crafting the law to prevent Black citizens from voting by targeting crimes they were believed to commit.

The state constitution strips voting rights from people convicted of 10 felonies, including forgery and bigamy. The Mississippi Attorney General issued an opinion in 2009 that expanded the list to 22 crimes, including timber larceny, carjacking and felony-level bad check writing.

Bain leads the House committee with jurisdiction over the state’s criminal code, and he has repeatedly said the Magnolia State should have a more consistent, fairer way to decide who has their voting rights restored instead of having politicians decide the outcome.

Bain last year led the efforts to clarify that those who have had a disenfranchising crime purged, or expunged, from their criminal record can obtain their voting rights back.

But Reeves vetoed that legislation because he believed it “created a pathway to restoring rights” that went beyond what the state constitution allowed.

READ MORE: Gov. Tate Reeves vetoes bill easing Jim Crow-era voting restrictions

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.