Featured

Note to Former NFL Players: Don’t ‘Pass’ on Regular Health Checks

By Ruth Cummins

University of Mississippi Medical Center Communications

John Fourcade has 28 surgeries to show for his years as quarterback for the University of Mississippi and the New Orleans Saints.

“Elbow, knee, shoulder – that’s football,” Fourcade, a New Orleans resident and ESPN New Orleans radio analyst, explains. “You don’t have to just throw the ball to get hurt. It’s just wear and tear. It’s getting tackled.”

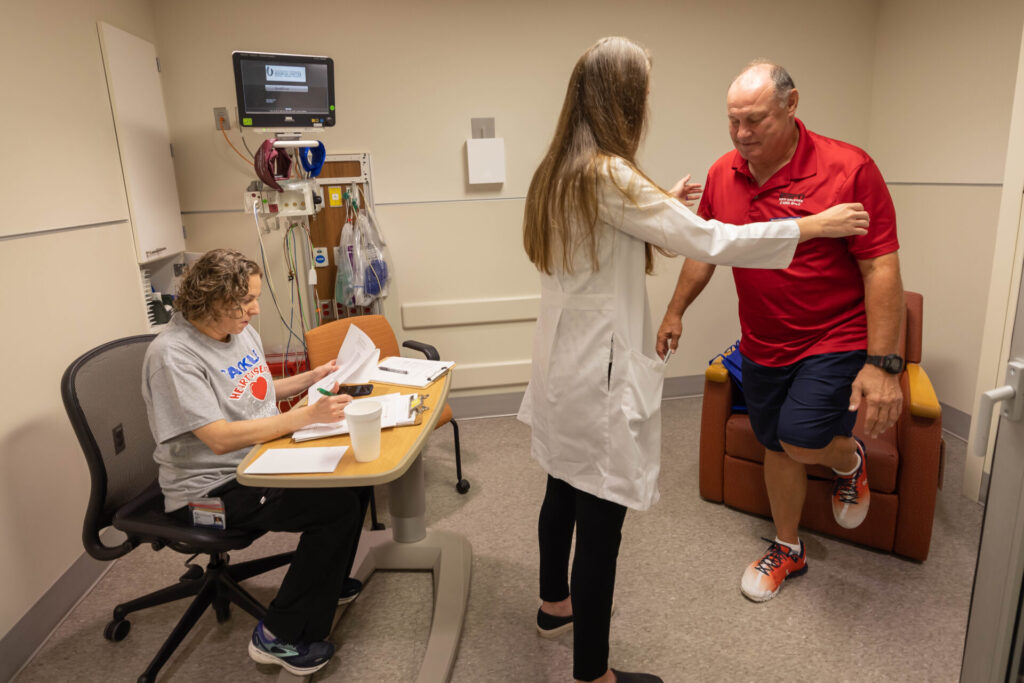

On Saturday, Fourcade was one of about 15 former professional football players evaluated at the University of Mississippi Medical Center’s University Heart for cardiovascular, orthopaedic and neurological issues, some tied to their playing days. The free testing and consultations with UMMC providers, also extended to eight of the players’ wives, were offered by the Medical Center in partnership with the nonprofit Living Heart Foundation and its funder, the NFL Players Association.

Like many people their age, men who played professional football decades ago might not seek regular checkups or care for chronic conditions, or might not know that a long-term health problem could prove dangerous. And with football being a sport where players take repeated hard hits, some former players may have suffered brain or joint injuries that years later remain undiagnosed or undertreated.

UMMC is one of five sites across the country hosting evaluations this year, said Scott Perryman, chief operating officer at the Living Heart Foundation.

“We find a lot of early signs of diabetes and hypertension. A lot of guys are struggling with their weight,” Perryman said. “We do echocardiograms and ultrasounds. We’ve found thickening of the heart muscle, or that the size of the heart can be in the upper limit.

“In some instances, players will need intervention. We’ve had one who needed open-heart surgery and one with a clot in the carotid artery,” he said of past screenings sponsored by the Foundation and NFLPA. “But most of all, we identify lifestyle issues they are having.”

Fourcade believes the reason why he drove upward of three hours to UMMC is simple. “Why wouldn’t you?” he said.

“I’ve had lots of orthopaedic visits, but sometimes you don’t see the inner part – the head and the heart. I want that feedback. I did this in 2013, and I’ll do it any time I can get the chance from the NFL.”

The Living Heart Foundation was created in 2001 by Perryman’s stepfather, Dr. Archie Roberts, a retired cardiothoracic surgeon, to combat sudden cardiac death and to provide risk stratification using early intervention for former players who cope with cardiac, pulmonary and metabolic conditions. Roberts played for the Cleveland Browns and Miami Dolphins.

The goal: Use the Foundation’s integrated-preventative approach to detect disease and intervene early. It allows athletes to avoid chronic uncorrected medical problems and to increase their compliance with treatment so that they can be their healthiest self. The Foundation provides services to specific groups that traditionally have been overlooked, especially high school, college and professional athletes.

“As a state, we have the highest rate of NFL football players per capita in the nation,” said cardiologist Dr. Mike McMullan, one of the event’s organizers and director of UMMC’s Division of Cardiovascular Diseases. “There’s definitely a need when we are the state with the most heart disease, and we have players who are concerned about neurological injuries during their playing time.”

“Our state has huge needs, and I’m excited that the Foundation reached out to us to provide these services,” he said.

Former pro football players can be at risk for both disease and injuries that were untreated since they were on the field, McMullan said. “They’re such big guys to begin with, and a lot were linemen,” he said. “They might be battling high blood pressure or heart disease. They had heavy weight on their joints, hips and shoulders.”

Another concern is chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a form of brain degeneration sometimes found in people who played football or other contact sports who suffered numerous concussions and head traumas through the years. It’s a diagnosis made at autopsy, when sections of the brain are studied.

CTE can produce cognitive, mood and motor changes, such as difficulty thinking and memory loss, impulsive behavior, depression or suicidal thoughts, or symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

“Some of the concerning things can be behavioral changes or aggression,” said Dr. Ed Manning, a professor in the Department of Neurology. “One isolated concussion is probably not going to create longstanding problems, but the science is still out on how many blows to the head or concussions can occur before you get concerned about the risk.”

Because football players are at great risk for brain injury, McMullan said, “this is a great screening opportunity to evaluate these folks.”

Jackson resident Perry Harrington was a running back for Jackson State University and the St. Louis Cardinals. He copes with macular degeneration, but has no longstanding football injuries that he knows of.

“This is an opportunity to make sure my health is OK,” Harrington said as he rotated from evaluation to evaluation, including checks for sleep apnea and nutritional and wellness counseling.

Did he have a few concussions along the way?

“Anybody who plays football and tells you they haven’t had a concussion … They’re lying,” Harrington said. “They say you see stars when you get hit hard. I’ve seen a lot of white dots.

Fourcade shared a concussion memory during his evaluation with orthopaedic surgeons Dr. George Russell and Dr. Derrick Burgess.

“I can still remember the Minnesota game. I got hit hard, and they asked me, ‘Do you know where you are?’ I said, ‘A state of confusion.’

“I went back in, and I threw a perfect touchdown. I threw the ball, and he was open.”

Problem was, Minnesota did the scoring, not the Saints.

Also taking advantage of the evaluations was Rodney Phillips of Jackson, who played for the Los Angeles Rams and the St. Louis Cardinals. He’s president of Mississippi’s 178-member former players chapter of the NFLPA.

“I haven’t gotten all of my results back yet, but my blood pressure is pretty good,” he said as he traveled through each evaluation station. “My weight is way out of range. I had a neck injury that literally ended my career, and I still have back spasms and soreness. I recently had carpal tunnel surgery and the other hand has been recommended for it.

“The weather forecast is in my knees and my hips.”

Data from all evaluations are tracked by the Living Heart Foundation, Roberts said. “We emphasize that if they have any abnormal results, that they need to get it taken care of or it could cause problems,” he said.

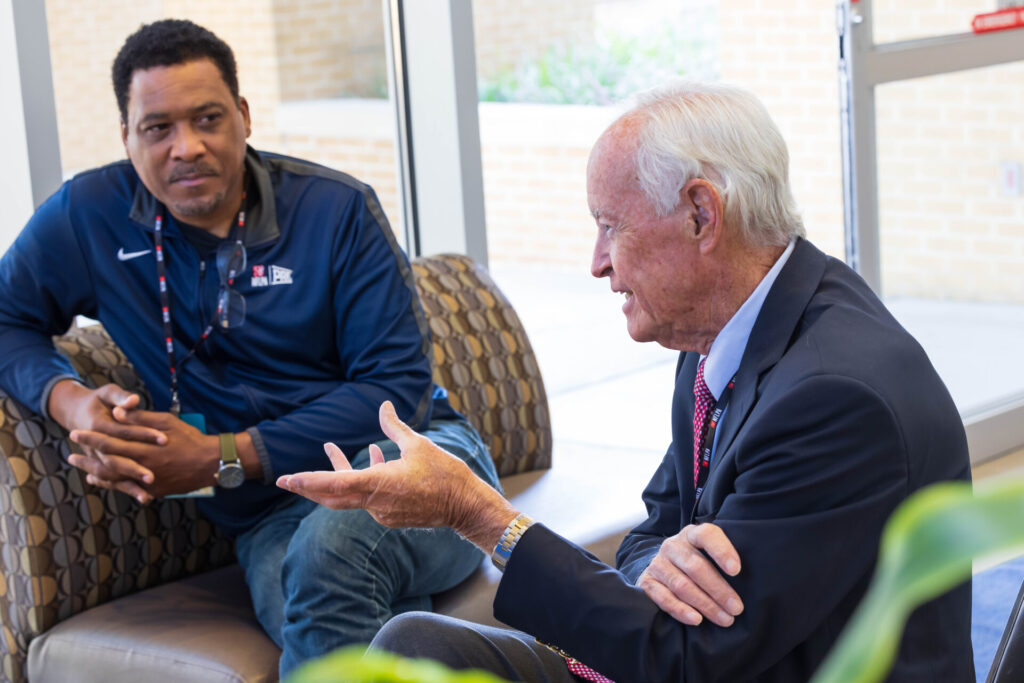

Andre Collins, executive director of the Professional Athletes Foundation at the NFL Players Association, enjoyed a long career as a linebacker with the Washington Redskins.

“It’s the full suite of health care that is happening here today, and we’ve tried to add features as the years go by,” he said. That includes help and resources for emotional or mental health struggles, Collins said.

It also includes advice on healthy eating, exercise and preserving your well-being. Dr. Josie Bidwell, an associate professor in the Department of Preventive Medicine and a Lifestyle Medicine family nurse practitioner, gave out valuable tips on how to create a healthy plate and other nutritional do’s and don’ts.

“We try to set realistic goals, like maybe adding a serving of fruit every day with the goal of shifting the balance of the plate to more plant-based,” she said.

Each player and the wives evaluated sat down with a provider to go over their evaluations before leaving University Heart. They’ll all receive a letter with recommendations for treatment and follow-up.

“We’re a close community,” Collins said. “This program has helped former players tune in to what’s going on with their bodies. What we find are problems that need to be worked on. We want players to get to their doctors and get checked over.”