Featured

UM Community Remembers Jere Hoar as Tough, But Caring Professor

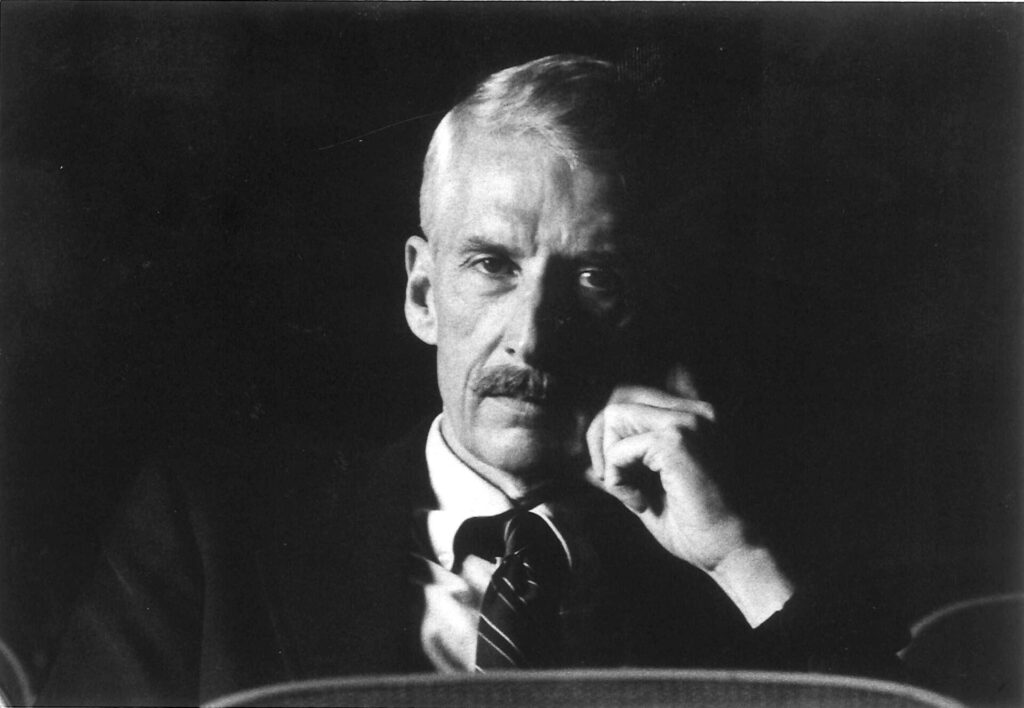

Jere Hoar, who taught journalism at the University of Mississippi for more than 30 years, was legendary for being a tough but caring mentor who enthusiastically pushed his students toward greatness because he believed in them.

By Michael Newsom

University Communications

Jere Hoar, who taught journalism at the University of Mississippi for more than 30 years, was legendary for being a tough but caring mentor who enthusiastically pushed his students toward greatness because he believed in them.

Hoar died Oct. 2 in Pontotoc, at 91. A private family graveside service was held with Hoar’s son, Dr. Ben Hoar, and Rev. Warren Black officiating, and a public celebration of his life and career is being planned.

Born in 1929 in Dyersburg, Tennessee, Hoar taught at UM from 1956 until he became professor emeritus in 1986 and taught part-time in that role until 1992.

Legendary former Boston Globe correspondent Curtis Wilkie was one of Hoar’s former students and remembers the classroom had a strict, almost military-level discipline to it. Wilkie recalled that Hoar presided over it formally, always leading lively discussions and calling students by “Mr.” and “Ms.” The professor was always to be called “Dr. Hoar.”

Wilkie remembers he got an F in advanced reporting – a class he would later teach at the university for more than 20 years – under the professor.

“I was only about 15 or 20 minutes late turning in an assignment and he flunked me,” Wilkie said. “What I say about it is I learned a very good lesson. I don’t think I ever missed a deadline in my newspaper career.”

Wilkie said retaking the course in the fall of 1962 to complete his degree kept him at Ole Miss long enough to witness the riots over the enrollment of James Meredith, the university’s first Black student, an event that shaped him as a budding journalist. Since he had to retake the class, Wilkie was also on campus for the 1962 football season, which ended with Ole Miss as national champions and the only undefeated, untied team in school history.

Like Wilkie, many more students have similar stories of being pushed to become better versions of themselves through their time in Hoar’s class.

“Jere was very smart and just a damned good teacher,” Wilkie said. “He was a good friend to a lot of his former students, who were then therefore safe from him and his classroom. He’s got a multitude of alums who just became friends with him and very fondly remember him.”

Wilkie was one of Hoar’s former students who, in 2000, helped establish the Jere Hoar Journalism and New Media Scholarship Endowment, which recognizes students with Hoar’s same dedication to journalism and desire to work hard in the communications field.

At his farm east of Oxford, Hoar also raised English setter bird dogs, Tennessee walking horses, St. Croix sheep and herding dogs for more than 50 years. He loved quail hunting and participated in dog field trials and horse shows. He wrote both nonfiction and fiction, short stories and books, and he loved to read.

He served in the U.S. Air Force during the Korean Conflict. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Auburn University, a master’s degree from UM and a Ph.D. from the University of Iowa.

A testament to his rare intellect is that Hoar also was one of only 16 people to ever successfully complete the Mississippi Preceptorship Program in Law and pass the Mississippi Bar exam to become licensed, even though he never attended law school.

When his father bought a daily newspaper in Troy, Alabama, Hoar got his start in journalism by working in the print shop setting “hot type.” By age 16, he was the police reporter, and by 17 he became the paper’s secret editorial writer despite his youth. He later was news editor of the Oxford Eagle and the Journal of Southern Commerce newspapers, and editor of Iowa Publisher magazine.

Robin Street, UM adjunct instructional assistant professor of integrated marketing communications, took media law from Hoar. An exceptional student, Street got the only B she ever received in a journalism class from Hoar. She was disappointed, but after talking with fellow classmates about their grades, she felt fortunate.

His classroom discussions were lively. Street said she remembers very clearly sitting in a classroom in Farley Hall, long before it was remodeled, and having Hoar ask her a question that completely stumped her. He asked whether something written in the sand, and washed away by the ocean, could still be considered defamation.

“I did not know the answer and was so embarrassed!” Street said.

But there was a lot more to Hoar than just the stern, intimidating side students saw of him in his classroom.

“I discovered he had a caring side,” Street said. “I learned that after I called him when I called to ask how I did on one of my media law exams.”

Street hadn’t done as well on the exam as she had hoped and was upset. She hurriedly got off the phone with the professor because she began to cry.

“A few minutes later, though, my phone rang and it was Dr. Hoar calling back,” Street said. “This was before caller ID existed and he would have had to go to some trouble to find my phone number. He said that I had seemed upset and he was calling back to check on me.”

That event shaped how she treats her own students, she said.

“I was stunned because I had thought of him only as that stern figure until then, but he clearly cared about his students,” Street said. “I have used that memory to guide me in my own teaching to always honor and respect students’ feelings.”

Mike Tapscott, a Tupelo attorney, remembers Hoar as his academic adviser in the 1970s.

“Except for the football coach who doubled as my sixth-grade geography teacher, Dr. Hoar was the most intimidating teacher I had,” Tapscott said. “He would mispronounce my last name, incorrectly placing an emphasis on the first syllable. Do you think I told him he was wrong? Absolutely not. I figured he knew better than I how to pronounce my own name.”

“He mellowed, though, and was gracious when I would run into him years later.”

Tapscott took law and ethics of the press from Hoar during the summer of 1977, after transferring to Ole Miss in January. The professor wondered if Tapscott was ready yet, he said, but he somehow found a way to excel in the classroom.

“As my adviser, he cautioned me against taking his class so soon after enrolling at Ole Miss,” Tapscott said. “‘It’s hard,’ he warned me, and he was right. Still, I made an A and have never been prouder of a grade.”

Donations in Hoar’s memory can be made to the Jere Hoar Journalism and New Media Scholarship Endowment by sending a check, with the name of the endowment written in the memo line, to University of Mississippi Foundation; 406 University Ave.; Oxford, MS 38655, or the charity of the donor’s choice.