Athletics

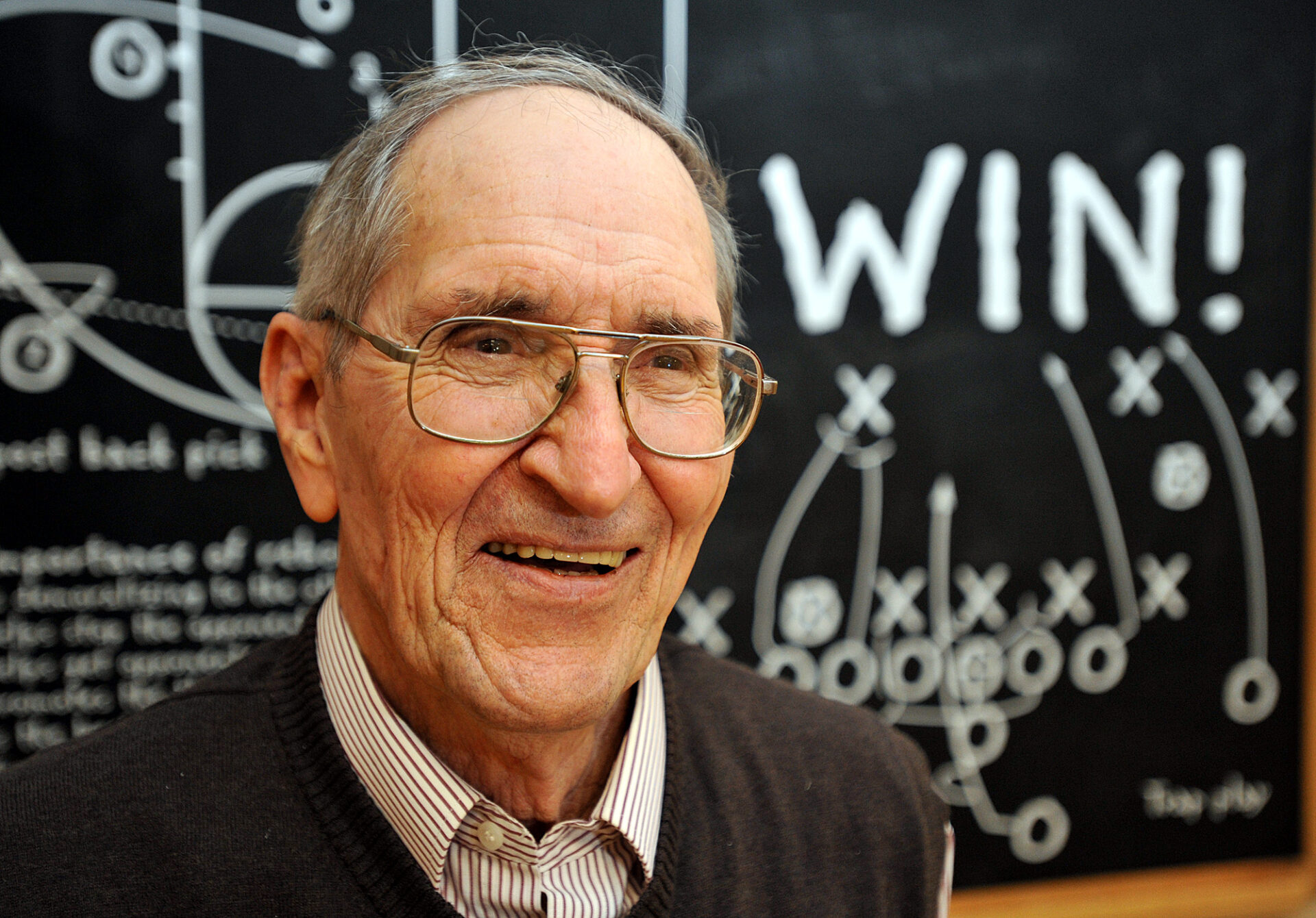

RIP Jack Carlisle, who often won, and always did it his way

By Rick Cleveland

Mississippi Today

The first time Mike Dennis met Jack Carlisle was in the summer of 1961. Dennis – a remarkable running back nicknamed “Iron Mike” – was about to play his senior season at Murrah High School. Carlisle was the new Murrah head coach, a thin, wiry, man who wore thick glasses and walked with a decided limp.

Dennis’s first impression?

“Well, I thought he was a hard ass,” Dennis said Wednesday morning, the day after he learned of Carlisle’s death. “I mean, he was a hard-ass guy, a tough guy who meant business and let you know it. We had 100 players to start the season. We ended up with 34 or 35.”

Dennis paused, sighing heavily, before continuing, “Yeah, he was a hard ass, but I learned to love that man. I can’t tell you how much he has meant to me. I give him credit for whatever I became.”

It should go without saying that when a man called Iron Mike calls you a hard ass, your rear end is harder than granite. Carlisle’s was. So was the rest of him.

Murrah went undefeated that regular season before losing to Barney Poole-coached Laurel in the Big Eight Championship game. Dennis went on to star at Ole Miss and then to play in the NFL.

Carlisle would have turned 92 in September. The last time Dennis had talked to his old coach was a couple of weeks ago when Carlisle was recovering from life-threatening heart issues. Dennis asked Carlisle how he was doing.

Said Dennis, “He told me, ‘Mike, I can’t see out of one eye, I can’t hear out of one ear, and I can’t walk at all right now, but other than that I am doing pretty good.’ What a great attitude he had.”

This will tell you much about the man known as Cactus Jack Carlisle, who lost a leg in a motorcycle accident when just a teen: In 1961, when Dennis met him, Carlisle already had been coaching for seven years. He would coach for 53 more, 60 in all. He was a ball coach. He was a sometimes crusty character. And he was a winner.

It was my good fortune to know Carlisle well in his later years, when he volunteered at the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and Museum, where his plaque (Class of 2004) is on display. We held a Jack Carlisle Roast at the MSHOF in 2012, which turned out to be one of the most grand events in museum history. The place was packed to the rafters and some people stood. So many stories were told. So much love and respect were expressed. And I can’t tell you how many hours I spent listening to his coaching stories. What follow are just three of so many. These are his stories. I’ll do the typing.

We begin in 1954 with Carlisle’s first coaching job at tiny Lula-Rich High School, north of Clarksdale. Lula-Rich had 14 players. One night Lula-Rich was playing at Oakland High, south of Batesville. There was no money for a bus — and, really, with just 14 players, one coach and a manager, no bus was necessary. The team made the trip in five separate cars.

“Well, it got to be 8 o’clock, gametime, and one of the cars hadn’t made it,” Carlisle said. “Turns out, it broke down on some backwater road in the Delta. It was carrying the left side of my line.”

Carlisle was down to 11 players and the manager, a kid named Harris. Carlisle asked Harris to dress out. Harris said they’d have to ask his mom. So Carlisle asked the mother, whom he knew as Miss Polly, a science teacher. Miss Polly wasn’t keen on the idea, but she reluctantly agreed.

Sure enough, Carlisle’s best player got hurt and was carried off the field.

“So I tell my manager to go in the game and just stand off to the side and stay out of the way,” Carlisle says. “I didn’t want Miss Polly on me if the boy got hurt.”

Very first play that followed: Lula-Rich was on defense and the smallish manager, draped in a uniform several sizes too large, stood 40 yards down the field. You’ve heard of the lonesome end? Harris was a lonesome safety. But, of course, an Oakland runner broke through the line and barreled down the field with blockers ahead of him. One of those blockers took dead aim at Harris and knocked him head over heels into next week.

“Here came Miss Polly down to the sidelines,” Carlisle says. “She grabbed her boy, took him to the car, and home they went. His career lasted one play.”

Years and years later, Jack Carlisle saw the manager’s photo in the Sunday newspaper. Thomas Harris had just written Silence of the Lambs. Thomas Harris, Miss Polly’s son and Carlisle’s reluctant safety, is the creator of Hanibal Lecter.

“I had no idea he would become a writer,” Carlisle says, “but I knew he was a little bit different.”

We move ahead now to 1971. Carlisle has just moved from public schools powerhouse Murrah to Jackson Prep, taking a few of his best players with him.

News spread quickly through the academy ranks. Teams began to find all sorts of excuses of why they couldn’t play Prep.

“I only had nine games, but I finally found a team in in England, Ark., that would come play us if we would pay them $1,500 and expenses,” Carlisle says. “Heck, I was desperate.”

The Arkansans showed up with 15 players, 15 little bitty players. It was like the Packers vs. Belhaven.

Carlisle played his first team for the first quarter only, but it was 45-0 at half.

Prep came back out for the second half. The other team did not. The referee delivered the news to Carlisle: “Coach, they say they ain’t playing no more.”

Carlisle went to the visitors dressing room. The coach told Carlisle his players refused to play. Carlisle asked if he could talk to them. The coach shrugged.

So Carlisle challenged their manhood. He asked them if they had no pride.

“Are you Arkansas men scared of some itty bitty Mississippi boys?” Carlisle challenged.

Carlisle also promised he would play only his fourth team, the jayvees. That probably was what did the trick.

Finally, one Arkansas boy stood. “I ain’t scared,” he said. Others followed.

Final score: Prep 66, England Academy 0.

“I might be the only coach to ever give a pep talk to the opposition,” Carlisle said.

Let’s move on to Ole Miss and the 1977 season. Carlisle was an offensive assistant coach for Ken Cooper, who would be fired at season’s end. The Rebels were playing mighty Notre Dame, which would go on to win the national championship that season. This was not a great Ole Miss team. The Rebels lost to Alabama by 21 the week before. They would lose to Southern Miss the following week. Notre Dame was No. 3 in the nation at the time.

“I was just hoping we wouldn’t get embarrassed. Size-wise and talent-wise, we weren’t their class,” Carlisle told me.

He felt no better when the Fighting Irish trotted out for the pre-game warm-ups in those famous, shiny gold helmets. Said Carlisle, “They were so big I thought the field was going to tilt their way. They made our guys look puny.”

Somehow – partly because of the mid-Mississippi heat and humidity and mostly because Notre Dame had yet to discover a sophomore quarterback named Joe Montana – Ole Miss trailed by only three points headed into the last five minutes. The Rebels got the ball back at their own 20. On the sidelines Carlisle and Cooper discussed strategy – somewhat heatedly.

Carlisle wanted to switch to Tim Ellis, the team’s best passing quarterback. Cooper was hesitant, to say the least. Carlisle convinced him but felt certain his job was on the line.

“I could see them talking,” Ellis told me. “I knew I wasn’t Cooper’s choice.”

So Ellis came off the bench, passed the Rebels down the field and eventually into the end zone. Ole Miss won 20-13, one of the most memorable victories in school history.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.