Featured

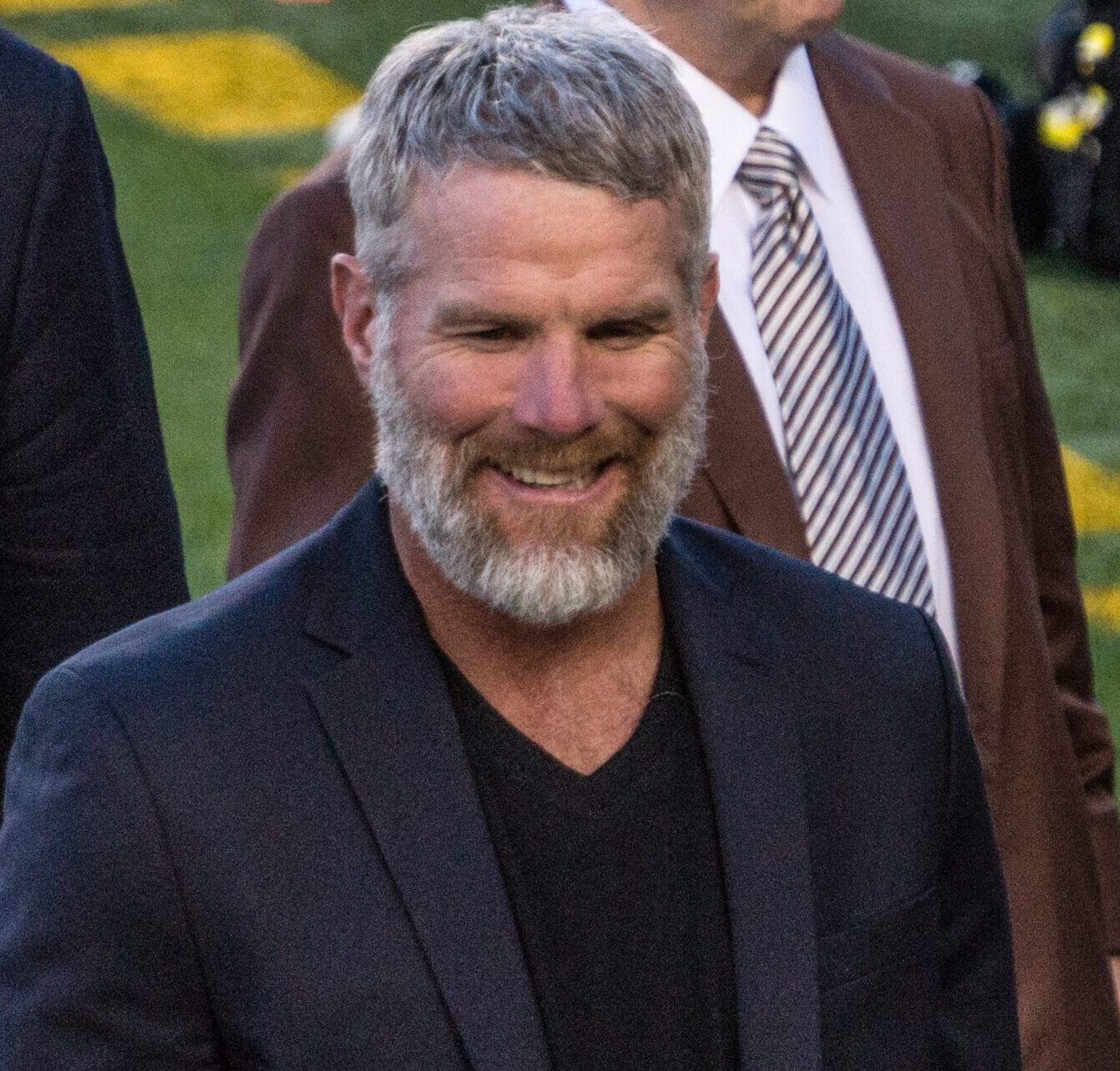

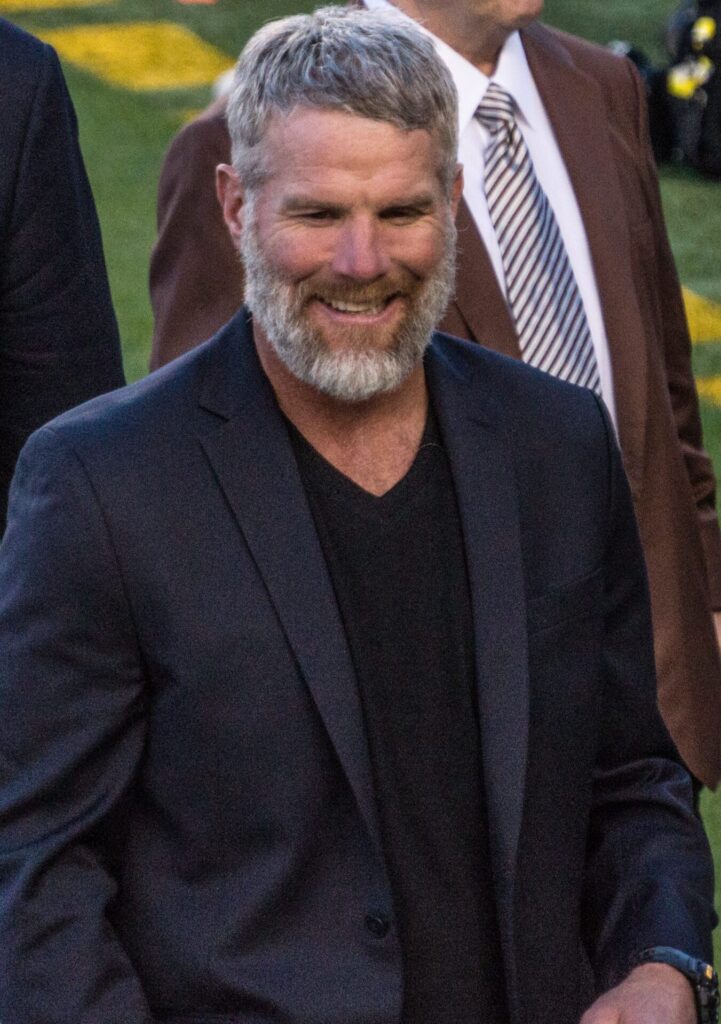

Brett Favre Hasn’t Returned Welfare Funds as Promised

Hall of Fame NFL quarterback Brett Favre has not repaid $600,000 he received in Mississippi welfare money after promising one year ago that he would.

By Anna Wolfe

Mississippi Today

Hall of Fame NFL quarterback Brett Favre has not repaid $600,000 he received in Mississippi welfare money after promising one year ago that he would.

A state audit released last May revealed that Mississippi Community Education Center — a nonprofit at the center of what officials call the largest public embezzlement scheme in state history — paid Favre $1.1 million in welfare money to promote a federally-funded anti-poverty initiative called Families First for Mississippi.

In explaining why he had entered a high-dollar sponsorship deal with the charity, Favre tweeted on May 6, 2020: “My agent is often approached by different products and brands for me to appear in one way or another. This request was no different, and I did numerous ads for Families First.”

His longtime agent James “Bus” Cook conversely told Mississippi Today when approached at his home last week that he had nothing to do with Favre’s contract with the public grant-funded nonprofit.

Favre, the 51-year-old Kiln native and south Mississippi resident, has not returned several calls or messages to Mississippi Today, but told his Twitter followers last year that he didn’t know the money he received was intended to help poor families.

Though officials have not accused him of a crime, Favre said he would refund the money. He made an initial payment of $500,000. Favre has not made any additional payments, a spokesperson for the auditor’s office told Mississippi Today on Thursday morning. Because federal authorities are still investigating the payment to Favre, no one has demanded he repay the funds. No other recipients whose payments were questioned in the audit have voluntarily refunded the money, either, the spokesperson said.

For a year Favre has remained mum on his involvement with now-embattled Mississippi welfare officials, instead expounding publicly about his support for President Donald Trump, how politics is ruining sports and his belief that Minneapolis cop Derek Chauvin didn’t mean to kill George Floyd.

But his million-dollar Families First advertising campaign isn’t the only way Favre intersects with the alleged welfare fraud scheme, which federal authorities are still investigating.

Favre met with the former Mississippi Department of Human Services director John Davis and the nonprofit founder Nancy New, according to emails and interviews, to discuss financially supporting a concussion research firm called Prevacus — the company that eventually received $2.15 million in allegedly stolen welfare funds.

Auditor’s agents arrested New, Davis and four others in February of 2020 for allegedly conspiring to embezzle a total of $4 million, which includes the payment to Prevacus.

Favre also talked to then-Gov. Phil Bryant about luring Prevacus to Mississippi, Mississippi Today first reported, but Bryant denied referring the project to the welfare department, an agency under the governor’s office. Officials have not accused Bryant of a crime.

Mississippi Community Education Center sent Favre Enterprises Inc., the football player’s for-profit company, a payment of $500,000 in December of 2017 and $600,000 in July of 2018. In the middle of 2019, Favre told Men’s Health he had invested nearly $1 million of his own money into Prevacus.

In an email, Davis told his colleague that Favre and Bryant wanted to meet Jan. 2, 2019, to discuss the “Educational Research Program that addresses brain injury caused by concussions,” as well as “the new facility at USM”. Bryant denied attending this meeting.

The nonprofit had also paid $5 million in human services block grant funds towards the construction of a new volleyball stadium at the University of Southern Mississippi, Mississippi Today first reported. Favre had been helping to raise funds for the facility at the university where his daughter played volleyball.

Meanwhile, the state was serving fewer and fewer poor families through the federal program Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, formerly known as welfare, that the defendants were allegedly using as a slush fund.

The state, which has one of the highest poverty rates in the nation at nearly 20%, has wide latitude to spend this annual $86.5 million federal block grant how it wants.

Because the state chose to transfer large chunks of the grant to the private nonprofit, investigators found that recipients of funds from New’s organization may not have known where the money came from.

“I would certainly never do anything to take away from the children I have fought to help!” Favre tweeted. “I love Mississippi and I would never knowingly do anything to take away from those that need it most.”

The $500,000 Favre returned to the state is in a custodial account at the office of the state auditor, a spokesperson said, where it will sit until the federal authorities finish their investigation and determine which expenditures constitute misspending and which dollars it will retrieve.

The current Mississippi Department of Human Services Director Bob Anderson has said he supports providing more direct assistance to poor Mississippians and pushed an increase to welfare benefits, the first increase since 1999, through the Legislature this year. The agency has also imposed much higher reporting requirements on its TANF subgrantees.

During Davis’ administration, the welfare agency did not require subgrantees to provide the agency with its partner contracts or a record of expenditures, such as Mississippi Community Education Center’s payments to Favre Enterprises Inc.

A contract Mississippi Community Education Center supplied to the auditor’s office said the nonprofit hired Favre for three speaking engagements, one radio spot, one keynote address and for autographs for marketing materials, according to the single audit. The contract did not contain a price, the audit said.

The auditor’s office has not released the contract, calling it an investigative record.

Investigators also asked the nonprofit for the dates Favre supposedly spoke and determined Favre did not attend the events, the audit said. The audit labeled the payment to Favre a “questioned cost.”

Favre denied taking money for a job he didn’t complete, saying he conducted “numerous ads” for Families First.

SuperTalk, a popular conservative radio station known for hosting state officials and employees, posted a photo of Favre posing with Davis and New at the office of TeleSouth Communications, another questioned recipient of TANF funds, in August of 2018.

Both SuperTalk and Favre have blocked Mississippi Today’s reporter from viewing their Twitter accounts.

While Favre implied on Twitter that New’s nonprofit approached his agent to set up the Families First gig, Cook told Mississippi Today last week that he had no knowledge of the deal.

Cook told Mississippi Today when visited at his home last week that he was not involved in Favre’s agreement with Mississippi Community Education Center, his efforts to get the volleyball stadium built or his investments into Prevacus. Cook said he had not discussed these topics with Favre and had read little about them in the news. He said he preferred not knowing.

Cook said he did not know if anyone else was representing Favre in these ventures, but that $1.1 million was not an unusual amount for Favre to earn for promotional gigs.

The attorney for Ted DiBiase Jr., Davis’ close colleague, previously told Mississippi Today and Clarion Ledger that his client recalled Cook’s attendance at a meeting at Favre’s south Mississippi home to discuss a partnership between the state and Prevacus, the company that received more than half of the allegedly stolen welfare money. Cook had not responded to several calls or messages over the last year, but he told Mississippi Today last week that he never attended such a meeting and had never met Davis or New.

Cook said he was also not aware of Favre’s promise to repay the welfare money he received to the state. When asked if Favre is the kind of person who does what he says he is going to do, Cook said he would expect Favre to follow through on his commitments.

This article first appeared on Mississippi Today and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.