The latest interview in the Ole Miss Retirees features Dr. Ken McGraw. The organization’s mission is to enable all of the university’s faculty and staff retirees to maintain and promote a close association with the university. It is the goal of the Ole Miss Faculty/Staff Retirees Association to maintain communication by providing opportunities to attend and participate in events and presentations.

Ken McGraw’s career path could have led him in several different directions from almost committing to the military, but he chose the Peace Corp instead. Then from Japan to Oklahoma, but the road to Ole Miss was his destiny.

Brown: Where did you grow up? What is special about the place you grew up?

McGraw: I grew up in the Memphis area, initially in mid-town Memphis where I attended Idewild Elementary (a few years ahead of Richard Howorth). We moved to the suburb of Whitehaven in 1952, which at the time was very rural—lots of woods and fields to play in. A great place for kids. We rode bikes to school, roamed freely, and had the idyllic life of middle-class white children in the 50s—moms at home tending to the kids as needed and playing bridge, canasta, or mahjong to socialize. Dads working in offices and golfing on weekends.

Brown: Where did you go to school?

McGraw: From ‘52 to ‘61 I attended public school in Whitehaven. But I didn’t graduate from there, because I got the opportunity to attend Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, for my senior year. I had gone there for a summer school session after my sophomore year. Then as well as now, elite schools value geographic diversity in their classes. Apparently, there was a spot for a boy from Tennessee, so I happily filled it. It was an eye-opening experience in so many ways. “Whitehaven?” one of my new classmates–Peter Formanek (who later in life started AutoZone) — asked. “Is there a Blackhaven?” Horizons shifted, becoming a much bigger landscape than I had known previously. And the classroom experience changed from rote learning to exciting discovery, but I had a lot of catch up to do.

Brown: What were you really into when you were a kid?

McGraw: Baseball was big. We had a little sandlot in the neighborhood where we constructed a backstop, made bases with sandbags, ordered some catcher’s gear from Sears & Roebuck, and played pickup ball. By age 10 or so we were eligible for Little League, so we graduated to a real field with a coach, umpire, uniforms, and chicken-shed style dugouts. All we lacked was an outfield fence, which was okay with me because I never could have hit one over it anyway. In 1957, Elvis came to Whitehaven. He joined in with some of the commercial businesses in town to sponsor a team—E.P. Enterprises, the team I played for at age 13 or 14. One of my teammates got a chance to talk with Elvis and told him that we—the team he sponsored—were doing well and headed to the league championship. Legend is—though I can’t verify for sure (and Elvis expert Brenda West doubts)—that Elvis responded by saying that if we won it, he would take us to Hollywood and introduce us to some girls.

Brown: What was your very first job?

McGraw: I graduated college in 1966 from Washington & Lee University in Virginia. The Vietnam War was raging then, and the draft was in place. What to do? My brother was already in the Navy as a carrier pilot and wound up with two deployments and 200 missions. I guess I was heading the same way, but a Peace Corps recruiter came to campus in my senior year, and his pitch won me over—spend two years in a third world country, do some good, learn a foreign language, travel some, be with other committed young people; in the context of the Vietnam War, it all sounded good to me. I signed up, got assigned to Tunisia, and after a summer of training, which included preparation as a teacher of English as a foreign language, flew off along with 85 other recent graduates to two years of what for most of us was the greatest thing we had ever done. Tremendous experience. Tunisia has a beautiful Mediterranean coastline and a couple of idyllic islands where many of my fellow trainees went, but I didn’t win that lottery. My assignment was a College Secondaire (High school) in Sidi Ali Ben Nasrallah, a town in the country center at the dead-end of the only road leading to it. The Peace Corps aspires to provide a total immersion experience. I got it. There were no Swedish tourists in Sidi Ali.

Brown: Did you have a mentor who influenced your career choice? How did you choose your career?

McGraw: Like for so many of us, my career choice was not a well thought out process. It just happened. The first step was moving to Atlanta in the summer of 1968 for a job in the public schools teaching English as a foreign language. There was a big need because of a flood of recent immigrants, mostly Cubans replaced north after escaping to Florida on Freedom Flights. I began taking evening classes at Georgia State University with the idea of maybe one day going to graduate school. Though I was an English major in college, I sought something with maybe a bit more relevance, so I gave psychology a shot. One of my first professors was John McCullers, who shortly thereafter left to chair the department at the University of Oklahoma. We stayed in touch and when I finished up a two-year assignment in Japan with the Fulbright program, he enticed me to Oklahoma for grad school. The land of 16-ounce steaks, buttered potatoes, and football was an attractive proposition to me after two years of raw fish, rice, and sumo wrestling, so I went and after four years, I had a career qualifying degree. Thanks to John.

Brown: What is your favorite thing about your chosen career?

McGraw: There’s so much to like about a career teaching at a university. Lots of interesting people to get to know, freedom to pursue whatever interests you, sabbaticals that afford the extended time needed for some projects, tenure that affords job security, a generally beautiful setting to work in, what’s not to like? Oh, I know. Faculty meetings.

Brown: Tell us about the interview process–who did you meet with, what position were you hired for, your impression of the Ole Miss campus, et cetera?

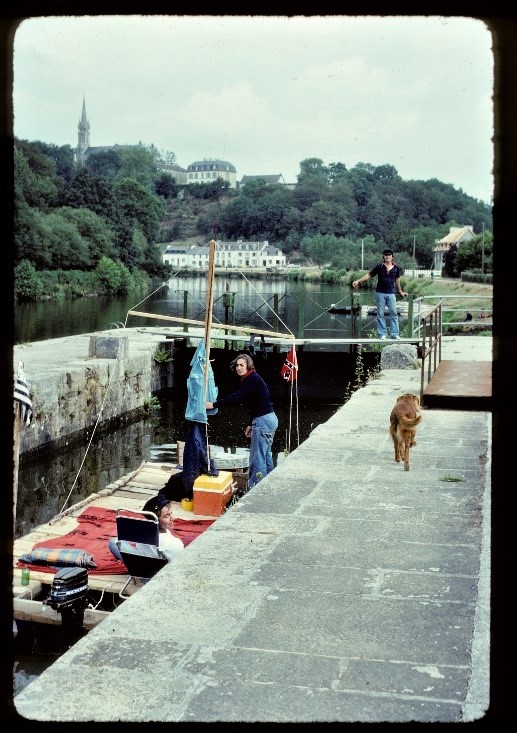

McGraw: I received my Ph.D. in 1976, which was a tight year on the academic job market. By graduation in May, I still did not have a job, so I took off for France for a float trip on the Loire River with three friends. Turns out that the Loire that summer was about as dry as the U.S. academic job market, so we wound up motoring our raft along a canalized river, the Aulne.

The trip extended into August when I got a telegram about a possible job offer at the University of Mississippi. I packed up, headed home, and called as quickly as I could after arriving in Washington. But it was a Sunday. I still hoped to find someone in the Psychology Department, so I called and got what I assume was a switchboard operator. When I asked for the Psychology Department, there was a long pause, then the operator came back on and said, “We don’t have one of those.” (Yes, she was searching in the S’s.) On campus, there was not a lot to be impressed by either. Those who have only known Ole Miss in the post-Martindale/McManus era would find it hard to imagine what the campus looked like in the drought of August before the irrigation and landscaping of today. Some of the buildings were less than impressive too. I recall my interview in the office of Vice Chancellor Chuck Noyes where there was a major rip in the carpet. But as with Sidi Ali, what started out as a not so promising situation turned into a great experience, this one lasting 30 years until retirement in 2006.

Brown: What were some of your responsibilities?

McGraw: One of the great things about schools like the University of Mississippi is that there is a lot of academic turf that is up for grabs. There are not a lot of vested interests guarding niches, so you get free rein to wander about in your interests. I started out as an experimental psychologist focusing on human development, then wrote a textbook, served as acting department chair for two years, shifted interests to applied statistics, then along with electrical engineering colleague, Mark Tew, started a free online laboratory—PsychExperiments—that got significant funding from the Dept. of Education and the National Science Foundation. I’m not sure moving about so much would have been possible in a larger, more competitive department.

Brown: What was the best time period of your life and why?

McGraw: Wow. That one is impossible to answer. It’s all been just great, and I must say, retirement in Oxford is right up there in the highlights list.

Brown: How did you and your wife, JoAnn O’Quin, meet?

McGraw: Jo Ann and I met here at the university. I had gotten to know her long before we dated, and we were great friends. I in fact introduced her to some of the guys I knew she might want to meet. But little by little, we opened our eyes to each other. Her best friend planted the idea that we were a good match. Hmm. Never thought of that, but it turned out the all-time best advice I ever got. We married in 1983, had two boys—Jake and Taylor, both of whom attended Ole Miss and benefited tremendously from the education and opportunities they were offered. Thanks so much to the Honors College, which along with Croft has changed the Ole Miss culture.

Brown: Your sons Jake and Taylor practically grew up on the Ole Miss campus. Where are they now and what are they doing?

McGraw: Since returning from graduate work in what Willie Morris referred to as the “other Oxford,” Jake has worked as a policy analyst with the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, which used to be on campus but is now a non-profit located in Jackson. The big news is he just got married to Kathryn James, an Ole Miss graduate and Mississippi Teacher Corps alumna. Taylor is in New York, where he went in 2012 when he entered the Teach for America program. His experience teaching first in Harlem, then in Brooklyn, opened his eyes to the inequities in the school system, and for the past three years he has been advocating for school reform via his website, The Bell, where he hosts the Miseducation podcast—now in its third season, and a student-led advocacy group, Teens Take Charge. Most people are surprised when they learn that New York City has the most segregated public schools in America, so a major part of the collective effort is to advocate for diversity in the schools. But there are other issues too, all of which stem from the fact that the wealthy and well connected in New York have tremendous advantages, and a ladder up for those lacking wealth and connections is pretty much lacking in the schools.

Brown: In your opinion, what attributes/traits predict success in life?

McGraw: More than any other, persistence. Talent helps. Training is essential. But persistence carries the ball.

Brown: What is your biggest pet peeve?

McGraw: Funny you should ask. I am dismayed by how much toothpaste stays in the tube, how much ketchup in the bottle, how much peanut butter in the jar. I heard a report years ago about a revolutionary coating that would allow us to completely empty containers of their contents. That was years ago, and it is not yet in the marketplace. I suspect there has been a conspiracy to block it.

Brown: What is your most prized possession?

McGraw: I guess you would have to say, our lake log cabin. It was my bachelor home, built in 1978. Over the years it has evolved about as dramatically as any house could evolve. It began as 760 square feet of primitive space, unheated in winter except for a wood stove and space heaters and uncooled in summers except for fans and a trick we learned of putting a sprinkler on the roof during the day (really does help). The man who came to install my wood stove that first winter, after looking around, said, “You must be single.” “How did you know?” I replied. “Because,” he said, “No woman would put up

with this.” Now though, it is quite a nice place, not only with central air and heating but all the other amenities, including high-speed internet. We’ve added on twice and acquired some extra land—quite important when you are in the county where zoning ordinances don’t restrict what neighbors might want to do. So, we spend a lot of time there.

Brown: I know you play golf. When did you start playing? Have you had that elusive hole-in-one?

McGraw: Yes, I play golf, and have played most of my life off and on but have never taken the game too seriously. I don’t even know all the rules and don’t follow all the ones I do know. Fortunately, the guys I play with regularly—Andy Mullins, Ron Dale, and Bill Kingery—feel the same, so we have a good time. I have in fact had a hole-in-one, on No. 5 at the university course, but truth be told, the shot was more lucky than good.

Brown: What do you prefer – a book, a movie, or a theater play?

McGraw: A book. No doubt about it. Neither Jo Ann nor I have made a habit of going to movie theaters, and though we have a couple of streaming services, we will go weeks without using them. Pre-Covid, Vaughn and Sandy Grisham hosted an Oscar’s night party annually, and they put us on their guest list for which we were grateful, but we were by far the least movie-literate people there. We were up against the likes of Ron Shapiro, Rosie and Robert Cooper, and Bob and Julia Aubrey. Holy Cow! They knew set designers! As for theater, I am so grateful that we have the Ford Center, the Ole Miss Theater program, and Theater Oxford at the Powerhouse, but plays aren’t a passion. We go as much to see friends and participate in the community as to see the performance. But books, they are a really favorite pastime. Twelve years ago, Dick Boyd—one of our golfing buddies at the time and a former Superintendent of Education in Mississippi—suggested to Andy Mullins and me that we start a book club, and we did. We’ve maintained a membership of 10 to 12–all guys, by the way, which turns out to be rather rare in the book club world. We met for years at Dick’s house and at some point along the way, we adopted the name, The Dick Boyd Book Club. To date, we’ve read and discussed 135 books communally. It’s been great fun and very rewarding.

Brown: What has been your routine since your retirement?

McGraw: One of the most rewarding aspects of retirement is not having a schedule, so most days’ activities are ad hoc, dictated by the weather, whim, and whatever needs tending to. Turns out, a lot needs tending to. Plus, in keeping with Parkinson’s Law, I’ve discovered that the time it takes to do a task expands to fill the time available. As our former colleague, Leland Fox once said, “I’m not sure what I do all day, but it takes me all day to do it.”

Brown: What is on your “bucket list?”

McGraw: No. 1 is making it to post-Covid and getting back to the rich social life Oxford affords. Enough with this Zooming!

Bonnie Brown is a retired staff member of the University of Mississippi. She most recently served as Mentoring Coordinator for the Ole Miss Women’s Council for Philanthropy. For questions or comments, email her at bbrown@olemiss.edu.