Charlie Spillers has led an interesting life and managed to have multiple successful careers in the process—military service, undercover agent, federal prosecutor, best-selling author. Here’s a glimpse into his many accomplishments, and an acknowledgment of his outstanding military service.

Brown: Where were you born and raised? Describe your hometown and what was special about it. Please talk about your childhood. Tell us about your parents and siblings. What’s your earliest memory?

Spillers: I grew up in south Mississippi but was born in Louisiana into a family with a rich Cajun French heritage. Living deep in the heart of Cajun country, my great-grandparents grew sugarcane near New Iberia, and couldn’t speak or understand English—they spoke only Cajun French. During our visits, my mother and grandparents, who spoke both languages, acted as interpreters.

For the first years of their marriage, my grandparents lived in a cramped, homemade houseboat tied to overhanging trees on a small bayou, a big change for my grandmother, who came from a well-to-do family in Saint Martinsville. They lived on game, fish, gardening, and bartering, and their only mode of transportation was a pirogue, a small wooden boat my grandfather paddled on the bayou. After the birth of my mother and her sister, they moved to Krotz Springs, a sleepy fishing village on the banks of the wide and deep Atchafalaya River. My grandfather made his living by fishing in the river with hoop nets in the summer and trapping mink and otter on the bayous in the winter. He was a renowned and widely respected hunter, and villagers talked about his special skill at hunting deep in the swamps.

Growing up, I often stayed with my grandparents during summers when I was seven to fourteen years old. Occasionally I accompanied my grandfather and his partner when they went out on the river in a bateau, a long, wooden flat-bottom boat, powered by a puttering gas engine, to check their nets, an exciting adventure on the wide, deep river.

French was dominant at their house. My grandfather listened to the news broadcast in French from radio stations in Opelousas and Lafayette, and he and the men who came by to visit would often talk in French. I couldn’t understand them but was fascinated by the mysterious French sounds and the animated discussions: gesturing hands, expressive eyes, and heads nodding and shaking. Perhaps without realizing it, during those summers I was learning at an early age to pay close attention to body language.

When the womenfolk came to visit my grandmother, she served small demitasse cups of strong Cajun coffee even when it was sweltering outside, and they would gossip in French so that I wouldn’t know what they were talking about.

Their home was filled with the delicious aromas and tastes of Cajun cooking: game stews made with thick brown roux, steaming chicken and sausage gumbos, spicy jambalaya, crawfish étouffée, and crawfish bisque. My mother cooked Cajun dishes she learned from my grandmother, and now my five sisters carry on the tradition. Instead of turkey, our family Thanksgiving dinners in Louisiana consist of large pots of chicken, sausage and seafood gumbo, potato salad, French bread, and wine.

The richness of our Cajun and French heritage is reflected by the last names in our family line: Borel, Frederick, LeBlanc, Savoie, Perrilleaux, Berthelot, LeTuiller, Giscair, and Dupuis.

My father’s side of the family came from England to South Carolina and then westward to Alabama and Mississippi, where Choctaw Indian became part of our family line, and then on to north Louisiana where my father was born and raised.

My father was a “tool pusher” in the oil fields, which meant that we moved every two or three years because his work followed producing fields. Changing schools became a regular but dreaded routine for me and my two brothers and five sisters. We moved around Louisiana and south Mississippi. In Louisiana we lived briefly in Baton Rouge, Krotz Springs, Cut-Off, Vidalia, and Ferriday; in Mississippi we lived in Roxie, Cranfield, Washington, Natchez, Brookhaven, and Magee, where I graduated from high school.

With each move, I was always the new student, the outsider, the stranger, walking hesitantly into a classroom full of kids who had grown up together. We had no shared history and I needed a way to get along with them. Years later those experiences proved to be an asset. While working as an undercover agent I was always the stranger, the outsider trying to find ways to be accepted by wary criminal groups of longtime associates and friends.

Brown: How did you respond when asked as a child what you wanted to be when you grew up?

Spillers: When I was in the first grade, in Natchez, I wanted to be an Air Force pilot and fly jet fighters.

Brown: Where did you go to school?

Spillers: Natchez; Krotz Springs, LA; Washington, MS; Brookhaven; Baton Rouge Jr. High. High Schools: Baton Rouge High; LaRose Cut-Off High, LA; Magee High School in Mississippi; Undergraduate: High Point College, NC; University of Louisville (KY); LSU, and Ole Miss; Graduate: Ole Miss Law School, J.D.

Brown: Tell us about your high school experience.

Spillers: I graduated from Magee High School in south Mississippi, where I spent the last two years of high school. The movie “American Graffiti” epitomized my high school years and experiences. Our graduating class was close and has remained close through the years.

Magee High School and the town have always felt special. More than any other place, it feels like my hometown, aside from Oxford where we have lived since 1980.

Brown: What were you really into when you were a kid? Did you play a lot of sports?

Spillers: For me, growing up in the 50s and 60s is represented by another movie, “The Sandlot,” where kids go out and play all day on their own and don’t come home until after dark. Those were wonderful years, filled with nonstop sandlot baseball games. And when dusk came, we would play Hide and Seek before finally going home.

When we lived in Cranfield, MS, which then was only a country store and a few houses, we would play all day long in a large abandoned gravel pit and the surrounding woods. The gravel pit looked like the scenes in TV westerns and we played cowboys and Indians in the Wild West.

Brown: What was your very first job, perhaps as a teen? What were your responsibilities and what was your pay?

Spillers: We lived in Brookhaven when I was in the 6th grade to the beginning of the 9th. The city or county had a temporary employment program during the summers for kids, providing two to four weeks of work and extra money. When I was 14, I worked on a road crew for two weeks, cutting weeds and brush along county roads with a sling blade, which was tough, but good work, during those hot summer days. Then I worked one or two weeks at a creamery, washing glass milk bottles all day. I enjoyed the work and earning pocket money. In the ninth grade in Baton Rouge I had a paper route with more than 200 customers.

Brown: After high school, you enlisted in the Marines. Did you ever second-guess that decision?

Spillers: At the age of 17, fresh out of high school in Magee, I joined the Marines. It changed my life. It was one of the best decisions I ever made – for two reasons.

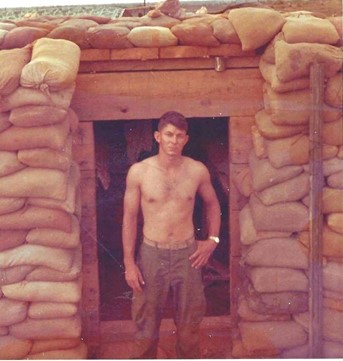

First of all, the Marines fulfilled my yearning for international travel and adventure. I was stationed at Camp Lejeune, NC the first two years and then volunteered for Vietnam. During the three years I was in the Marines, fought in the Dominican Republic and Vietnam; went through cold weather training at the Canadian border; I had bar fights and was stabbed during one fight; sailed the Caribbean for months on a helicopter carrier; visited St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands; Viejas, Puerto Rico; Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; and Santo Domingo; sailed across the North Atlantic; visited Spain and Portugal; sailed across the Pacific on a troop ship to Vietnam; and visited Japan on R&R from Vietnam.

After boot camp I became a rifleman in an infantry company based at Camp Lejeune, NC, but was soon selected for the two-man Battalion Secret and Classified Files unit. I was given a Secret-Crypto Security Clearance. Reading classified reports about Russian subs and military capabilities and about Fidel Castro’s internal discussions was exciting stuff for a teenager from Mississippi. I later became the Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) in charge of the Battalion’s S&C Files.

At the end of my two-year duty assignment at Camp Lejeune, I volunteered for Vietnam and served as a Squad Leader in Lima Company, 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines, 3rd Marine Division (L/3/3).

Second, and more importantly, the Marines instilled in me a mindset that has driven me throughout my life. That is: nothing is impossible to achieve, you can overcome any obstacle, always accomplish the mission and take care of your people. As an undercover agent, MBN commander, law student, federal prosecutor, attorney-advisor to the Iraqi High Tribunal and the U.S. Department of Justice Attaché for Iraq, I’ve been driven by that guiding mantra.

Brown: While you served in Vietnam, did you question your role in the war given that you were being shot at and at risk while doing your job?

Spillers: I asked to go to Vietnam and served there from December 1965 through most of September 1966. I was simply doing my duty and would do it again. During the early years of the war we never questioned why we were there. Then, it was simply “good versus evil,” and “democracy versus communism.” Beyond all that, we were Marines – which meant we fought where our nation sent us and did our best. Just as our Armed Forces do today.

Looking back, we see failed strategies for winning the war and the devastating waste of more than 50,000 young lives – along with the life-long emptiness and heart-breaking misery of their families. The bullet that kills a soldier doesn’t end there, it keeps going and it destroys and damages family and friends, forever.

For me, the war is a somber reminder of what matters. Shrapnel ripping my shoulder and enemy bullets hitting a few inches from my head provided a perspective on life. Later on, things that seemed bad weren’t quite as bad compared to that.

My blood soaked into the killing fields of Vietnam. We fought for each other there. But I also bled for the right of Americans to proudly stand and place their hands over their hearts when the national anthem is played. Despite my own views, I bled for the right of Americans to kneel when the national anthem is played. I fought and bled for the freedom of speech on which our democracy is founded. We all can disagree and still be friends. We all can disagree and each still love our country. More unites us than divides us.

Brown: While undercover, did you ever have occasion to “forget” your alter-identity?

Spillers: I used dozens of different undercover names and backgrounds, and sometimes used different identities at the same time with different groups. During 10 years undercover I forgot my undercover identity twice.

While in Intelligence with the Baton Rouge Police Department, I learned that a company in Baton Rouge was connected with organized crime and was sometimes a front for hiding fugitive criminals. I showed up and pretended to be a fugitive, and the company sent me to the Shreveport area to work on a crew putting siding on homes.

Drinking whiskey late the first night with the crew chief I learned everything about the criminal operation. The next day I worked muscles I didn’t know I had, and that night as the work crew sat together at a long dining table in the motel, I was so tired I couldn’t lift my head. I heard the crew chief mention the name “Sullivan” and in my exhausted state I thought, “Sullivan? Sullivan? I need to remember that name for my intelligence report. Who’s Sullivan?” Then I looked up and the crew chief and the all the crew were looking at me. “Isn’t that right, Sullivan?” he called out to me. “You worked your butt off today, didn’t you, Sullivan,” and I suddenly remembered. I WAS Sullivan. Duh on me.

On the way from one undercover meeting to another in Baton Rouge, I drove by the house of a heroin dealer I had dealt with several months before while using a different undercover name. On the spur of the moment I stopped to ask him if anything was happening. When there was no answer at the front door I went to the yard on the side of the house. As he came around from the back, I went blank and couldn’t remember the undercover name I had used with him months before. “Hey, man,” I said, thumping my chest, “Remember me, remember me?” almost pleading. “Oh yeah, Rick,” he said, to my great relief. Then I knew who I was. Duh on me.

I learned the hard way that a greater danger came from informants who sometimes forgot my undercover name and called me “Charlie” in front of criminals with whom I had just used another name. Those tricky situations required hurried excuses. For that reason, undercover agents often use their real first name and an assumed last name. In Baton Rouge I couldn’t use my real first name became it had become so widely known and was in newspapers and sometimes on TV. Sometimes criminals even warned me about me. In Confessions of An Undercover Agent I described someone testing my reaction by calling me “Charlie.”

Brown: I’ve read that it took you 12 years to complete your undergraduate degree and another 4 to finish law school. Had you formulated a plan for your post-undercover career with Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics?

Spillers: While serving as the Regional MBN Commander based in Oxford, I earned my BBA degree at Ole Miss and was suddenly driven to go to law school. It was something I had never thought about before. I was inspired by the federal and state prosecutors with whom I had worked as an agent: Assistant District Attorney Frank Gremillion in Baton Rouge; Assistant DA Tommy Mayfield in Jackson, and Tom Dawson, John Hailman and Al Moreton with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Oxford. I admired their professionalism and integrity, and their devotion to the rule of law. They were great role models. Later on, as an Assistant US Attorney myself, I was blessed to try cases with Al, John, and Tom, and to learn from them.

Brown: What accomplishments are you most proud of?

Spillers: Survival. It’s a blessing rather than an accomplishment. I was lucky and probably wore out a few Guardian Angels.

In addition to serving in Vietnam and making major undercover cases, I persevered for 16 years to finish college and law school while working fulltime. That hard-earned education gave me opportunities to accomplish things as a prosecutor, instructor, adjunct professor, mentor to new federal prosecutors, Attorney-Advisor to the Iraqi High Tribunal and Justice Attaché for Iraq.

In Iraq I helped advance cases of Genocide, War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity against high-level members of Saddam Hussein’s regime; worked closely with the Italian Embassy and the British government on matters with international implications; worked on improving the security of the Iraqi judiciary nationwide and disrupting Al-Qaida financing; and worked on other matters.

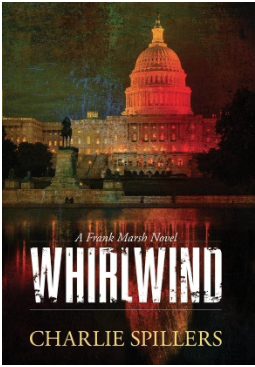

I’m grateful that Confessions of An Undercover Agent is so popular and has generated more than 150 book events, including newspaper, magazine, radio and TV interviews. It became an Amazon #1 New Release, was nominated for Best Nonfiction by the Mississippi Institute of Arts & Letters, was a frequent top 10 bestselling book in the state and was chosen by several bookstores as one of the best books of the year. The publisher recently ordered a third printing of hardcovers. Whirlwind: A Frank Marsh Novel felt special when I was writing it and I’m delighted readers find it hard to put down. It will be hard to top.

Other high points stand out, including this one as an instructor. When I taught new federal prosecutors at the DOJ National Advocacy Center (NAC), during the week I would have the same 8 or 9 prosecutors assigned to my courtroom each day for role-playing exercises on direct exam, cross exam, opening statements, etc. One new federal prosecutor had been a state prosecutor for 10 years in Puerto Rico, where his state trials were conducted in Spanish.

He spoke English fluently, but he was awkward and hesitant when doing the courtroom exercises. The other students would cringe when he was doing an exercise. One day he was particularly bad while examining a witness. I stopped the exercise and took the place of the witness. “Now,” I told the prosecutor, “I want you to continue your examination, but I want you to do it in Spanish.” I don’t understand Spanish but knew what he would be asking, and I responded in English to his line of questions.

When he switched to Spanish, he was a completely changed man. His Spanish sounded like beautiful music, he was confident, and his movements were fluid and assured. He looked like a graceful bullfighter. He had become a very experienced prosecutor again. When the exercise ended the students broke out in loud applause for him. I called a break and he rushed over and shook my hand. My eyes were a little moist, as were his. From then on he did the exercises in English and was one of the best in the group.

I’ve been blessed to have special moments like that touch my careers. Someone above surely guided my hand at times.

Brown: What are the essential skills you have to have as undercover agent?

Spillers: Obviously, an undercover agent must be able to remain calm and think clearly under high stress. He or she must have initiative; be self-reliant, resourceful, and self-motivated; have self-discipline, and be focused and driven. And constantly learning how criminals operate. Critical thinking and logical reasoning are important in anticipating how criminals will react and what they will do during undercover situations. You can then consider your own best approaches. “What can I expect in this meeting, who might be there, what if they ask me this or that, what if they want to pat me down for a wire or a gun, what if they have counter-surveillance and bug detectors, what if they want to go somewhere else, what if, what if… etc. What might happen unexpectedly?”

Here’s an example. In my last undercover operation smugglers delivered 3,000 pounds of marijuana to me and fellow MBN agent Ricky Peterson in Houston, Texas. We were to meet my smuggling contacts at the Houston airport and from there they would fly Ricky by helicopter to a ranch about 50 miles away to see the load of drugs. He would then vouch to me by phone for the drugs and I would pay them a half million dollars.

The problem was that they would be able to hold Ricky hostage until the delivery and payment were concluded. Even though DEA was prepared to follow the helicopter and raid the ranch, Ricky would be under the control of the bad guys and in extreme danger. No matter how quickly DEA could rush in, it would only take a split second for smugglers to put a bullet in his head. I wouldn’t let him take the risk and that miffed the DEA supervisor who wanted us to do it. I kept refusing and finally told the supervisor to give me one of his agents to pretend to be one of my men, and that agent, instead of Ricky, could go by helicopter with the smugglers. He didn’t want to do that and it ended the disagreement. After that we worked smoothly together, and he was great.

We met the smugglers at the airport, declined the helicopter trip, showed them a half million in cash and I told them how I wanted to do the deal. We went to a motel with the smugglers and after two days of almost nonstop negotiations they finally agreed. In dozens of meetings at the motel we needed logical reasons to refuse to do the deal their way and to insist on doing it our (safer) way, while compromising on minor points. The smugglers insisted on seeing the half-million again ($1.5 million in today’s dollars) but that was extremely dangerous because of the risk they might rob or kill for the money. We finally figured out a way to show it fairly safely. The deal, arrests, and seizures went down smoothly, and no one got hurt.

Smaller transactions can require just as much work and creative thinking. During the first years I worked undercover there was no surveillance and no backup. You were on your own and no one knew where you were or what you were doing. It felt like walking a tight rope without a net. It was risky, exciting, and exhilarating to survive close calls and to succeed. But you could put yourself in much greater danger if you weren’t constantly thinking ahead and thinking clearly and quickly.

Agents often have to work with little or no rest. For instance, on the deal for 3,000 pounds I conducted two days of almost nonstop negotiations with little sleep and was physically and mentally drained by the end. When I taught undercover operations in the MBN Basic Agent Academy I kept the agent trainees awake most of one night and then ran them through numerous, stressful role-playing scenarios all the next day. It drove home that an undercover agent has to constantly function on a high level when stressed and exhausted. It’s not a game.

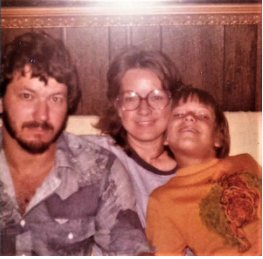

Brown: Were you able to share with your wife Evelyn the particulars of your activities during an operation/job? Did your family/siblings know you were an undercover agent?

Spillers: I sometimes shared work activities with my wife, Evelyn, but usually only in a general way because it had become routine for her. She was exposed to it all the time at home. When home, I was on the phone for hours each day and night with criminals, informants, and agents, and she could hear my sides of the conversations. I played undercover recordings at home to transcribe tapes and wrote reports and sealed evidence at the kitchen table.

When I left home for an undercover meeting, I didn’t know, and she didn’t know, if I would be gone for a few hours, most of the day or all night. When I was infiltrating auto theft rings in Northeast Mississippi, I would leave home in Jackson for days or a week at a time, but neither she nor I knew for certain when I would return. After a day or two at home I would be gone again and we had little contact during those absences. That had to be especially burdensome on her in addition to anxiety about my work.

She knew that when the phone rang at home I was John, Frank, Mike, Rick, J.R., Glenn or any name the caller asked for, and that she was “my old lady” or girlfriend if they wanted to leave a message. She had her own close calls and I wrote about those in “Confessions of An Undercover Agent.” My parents and siblings generally knew I was working undercover but didn’t know the particulars of what I was doing, or where or how, except when it was in the newspapers or on TV.

Brown: How difficult/easy was it to assume a new identity/role?

Spillers: Assuming new identities and roles came easily, and were backed up by undercover drivers’ licenses, cars, and tags, but it sometimes required more thought to figure out the best role to assume.

For example, when infiltrating Dixie Mafia auto theft rings, I didn’t know enough about auto theft operations to be credible with the criminals. So instead I assumed the role of a high-level member of a multi-state criminal operation. Thus, I could confine undercover meetings to negotiations for purchasing stolen vehicles and the logistics of moving cars to other states. I backed up the role with an undercover apartment in Tupelo, a telephone in my cover name and a business card for my “front company.”

When infiltrating a Mafia-linked air smuggling operation I assumed the role of a financier, as a wealthy Memphis businessman tied in with organized crime in the Northeast U.S. In that operation I had to be the script writer, producer, director, and actor. Other agents did great jobs pretending to be my banker, my men, and my mistress.

I also chose particular types of names to go with the roles I played. If I wanted to seem younger, I would use a softer, younger sounding name, usually ending in a “y,” like Ricky, Henry, or Mickey. If I wanted to seem older or harder, I would use a harsher sounding name like Frank or John. I respectfully offer my apologies to all the Rickys, Henrys, Mickeys, Franks, and Johns out there.

Brown: Was there ever a time when you did not feel supported during an undercover job? If so, how did you deal with it?

Spillers: I always had the support I needed. In Baton Rouge, and in the early years while working undercover with MBN, I usually didn’t have surveillance for routine undercover – but I liked it that way. Agents conducting surveillance could be spotted, which would raise suspicions about me, so I often felt more comfortable without surveillance. On the other hand when I did have surveillance, they always did a great job.

In some operations, surveillance was impossible. For instance, when I was infiltrating auto theft rings in Northeast Mississippi there was no way agents could follow me each day and night without being compromised as I visited numerous criminals over a wide area. I was on my own. But when criminals delivered stolen vehicles to me agents were able to conduct surveillance.

Brown: Were you ever given an assignment that you would have preferred to decline? And did you? Or could you?

Spillers: The thought of declining an assignment never entered my mind. The assignments were worthwhile, and undercover was my job and duty no matter how risky.

I might be asked to work undercover in a certain area or on a group of targets, but I chose who I would work on and how I would do it. For example, I might be asked to work undercover on the Gulf Coast to infiltrate heroin trafficking or infiltrate an international air smuggling operation. But it was up to me to decide what to do and how to do it.

It required lots of creative thinking. I loved the fact that working undercover required every bit of my capabilities and pushed me to my limits.

Brown: You obviously were amongst some very unsavory characters. How well did you adapt in that environment? What was your salvation?

Spillers: For an undercover agent, success and survival depend on establishing and maintaining credibility in your undercover role. I not only pretended to live the role I became the role. I was able to think like the character I played, and that was evident to the criminals I dealt with.

Brown: Given your ability to assume a new identity, and the excitement and adrenalin rush of being a “bad boy”, did you ever fear you just might cross over to the “dark side?”

Spillers: Undercover can be gritty and grinding, but some undercover roles are glamorous. That can be intoxicating, but working undercover is exciting enough by itself and the thought of crossing to the dark side never entered my mind. No matter how deeply I entered into the role of being a criminal I never forgot that I was a law enforcement professional on a mission.

Brown: You readily admit that your work took a toll on your wife and son. Looking back, what would you have done differently if anything?

Spillers: During the ten years I worked undercover we didn’t have normal family life. I discussed this in the book “Confessions of An Undercover Agent.” Looking back, I wouldn’t have worked undercover that long, perhaps two years at most. Although I did a lot of good and made cases on criminals who may not have been caught otherwise, the price on our family life was too high.

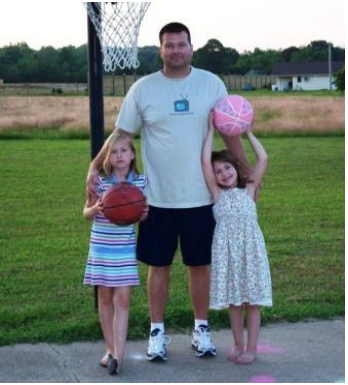

Unfortunately, the disruption of our family life didn’t end forever after I stopped working undercover. As an Assistant U.S. Attorney in Oxford I prosecuted members of violent street gangs from Clarksdale. While doing time in federal prison two of the convicted gang members plotted with other gang members on the outside to kill our granddaughters Michaela and Hannah who were in elementary school at the time. The gang members thought the girls were my daughters. The Bureau of Prisons discovered the plot, and an investigation was quickly launched to identify their conspirators on the outside.

Meanwhile, DOJ, the U.S. Marshal’s Service in Oxford and the Oxford Police Department couldn’t have responded any better than they did. U.S. Marshals and the Oxford PD Swat Team diagramed our homes in case they had to respond. Oxford PD increased patrols in the neighborhoods where we lived and where the girls lived with their dad and mom. The school resource officer carefully looked out for them. And DOJ had alarm systems installed in our homes. I carefully watched cars cruising past our home and even jumped in my car and followed a few suspicious vehicles. After a month, the plot was quashed when investigators went to the prison and confronted the gang members. All ended well but it was a tense time.

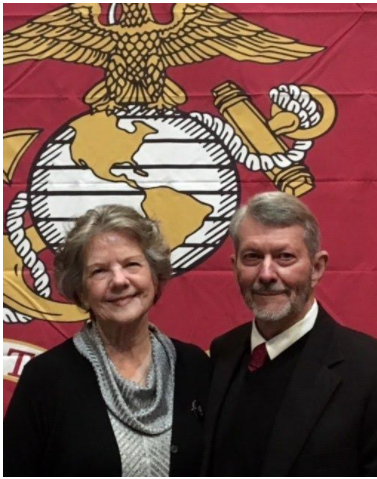

the Oxford High School Marine Corps JROTC, November 8, 2019

Brown: Was it difficult for you to adapt to your “normal” job as an attorney/prosecutor?

Spillers: Going from law enforcement to becoming a prosecutor was an easy transition because both professions are part of the criminal justice system, and dedicated to investigations, fact-finding and making cases on criminals.

It was more difficult coming back to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Oxford from my three tours serving in Iraq for the Department of Justice (DOJ) where I had worked on cases involving chemical warfare attacks by Saddam, torture, and massacres of thousands. During my first two tours in Iraq, I worked on War Crimes, Genocide and Crimes against Humanity cases for the Iraqi High Tribunal. I helped identify and organize evidence and law on Saddam’s chemical weapons attack on the town of Halabja which killed 5,000 civilians; the “Marsh Arabs” and “Friday Prayers” cases that involved massacres of tens of thousands of Iraqi civilians. I traveled to Belgium and interviewed a scientist who had collected chemical warfare samples in Halabja while the town was still strewn with bodies of men, women, and children. I analyzed witness and victim statements and transcripts of Saddam’s meetings with his Revolutionary Council during which they planned crimes against humanity. I watched testimony before the Iraqi High Tribunal about tortures and mass murder, including the genocide of 280,000 Kurds. They killed so many that bulldozers dug separate trenches for the bodies of men, and for women and children.

In my third tour of Iraq, I served as the U.S. Department of Justice Attaché for Iraq, which was a Senior Executive Service (SES) policy-making position. I worked with the Embassy, State Department, the military, Iraqi ministries, other agencies and nations. Each time I returned from Iraq, the cases here that had seemed so important before no longer seemed to matter as much in light of the mass genocide and chemical warfare that killed hundreds of thousands of Iraqi men, women, and children.

Brown: When did you know you had a book in you to write about your undercover experience?

Spillers: As a federal prosecutor working with dozens of federal, state and local law enforcement agencies, and countless agents, and I began to realize that my undercover experiences were fairly unique in the profession. I had worked on a wide variety of criminals: burglars, safecrackers, drug traffickers, international smugglers, members of auto theft rings and other career criminals. Very few had worked undercover as long as I had or on such a variety of crimes.

I thought people would enjoy reading about those experiences – not because they were about me, but simply because the adventures and close calls were interesting, no matter whom they were about. About 20 years ago I typed notes about my undercover experiences and then set it aside. Years later, my friend, neighbor and fellow author John Hailman encouraged me to write and he was instrumental in getting University Press of Mississippi (UPM) interested in a book.

Writing about my experiences was a revelation. I was surprised I had experienced so many close calls and tight spots. Here is a summary of many tense moments I wrote about in various chapters.

“My insides twisted as the safecracker pressed a cocked gun in my side, his finger on the trigger. / Junior grabbed the gun and was raising it to start shooting as I grabbed his arm / The heroin dealer held a gun as he carefully looked me over and watched outside for surveillance. I prayed agents wouldn’t drive into the cul-de-sac outside the house. / They had mistaken him for me and the bullet missed his head by inches. / A gunshot cracked and we dove for cover.

He pointed the cocked gun at my undercover partner and I inched my hand toward my gun / As I stepped into the apartment for a drug deal someone recognized me and warned the others / With his back to me, a suspicious drug supplier stood at the bedroom window watching outside. As he turned around, we suddenly recognized each other – I had busted before. / Two men stepped into the all-night grill and headed to my table to meet me for a drug deal and I suddenly recognized one of them. I had busted him before. My heart was hammering as he slid into the booth beside me. / “If this turns out to be a bust” a dealer warned me, “someone’s gonna die.” His partner had a loaded 45 automatic.

Armed with a rifle, the two men planned to rob us. / A group of heroin dealers met to decide if I was a cop and whether they should kill me. / Stepping into a dark alley I recognized the drug dealer waiting to meet me – he knew I was an undercover agent / A group of drug dealers was coming through the door and I suddenly realized one knew I was an undercover agent. / He watched intently as I showed him a half-million dollars in cash. I tensed expecting a violent robbery. / I sat at the window in the dark, gun in my hand, trying to see if the members of the auto thief ring had followed me from our meeting. / We were isolated deep in the woods when I pulled out my unloaded gun and prayed that he wouldn’t come up shooting.”

Successfully handling a tight spot felt like barely dodging a terrible accident and winning the lottery all at the same time. As I wrote the book, I shook my head wondering why I didn’t stop working undercover in the face of increasing risks. But I had become addicted to the adrenaline rush and excitement. And it was satisfying to make cases that otherwise might never have been made.

Brown: You have had great success as a writer. What can we expect next from you?

Spillers: After “Confessions of An Undercover Agent,” I wrote “Whirlwind: A Frank Marsh Novel.” I’m almost finished with the sequel, which is named “Flashpoint: A Frank Marsh Novel,” and hopefully it will be released early next year. I’m already making notes for the sequel to “Flashpoint,” and thinking about a darker, deeper novel later and perhaps another nonfiction book after that.

Brown: What’s your creative outlet?

Spillers: Writing

Brown: What advice would you give to your 20-year-old self?

Spillers: Slow down, focus on family, don’t work as much and don’t live life at a breakneck speed. I’ve always worked hard and been totally focused on whatever I was doing, but I read something a few years ago that struck home. It was this: “You never see a tombstone which reads, ‘I wish I had spent my life working harder.’” I haven’t slowed down much but it made me think.

Brown: What’s the best part of your day?

Spillers: Mornings are good for that first cup of coffee and writing, and occasional yard work. Afternoons are perfect for working out on my StairMaster and lifting weights. Evenings are wonderful for reading and watching classic foreign movies.

Those are good while stuck at home because of the pandemic, but I’m looking forward to the time when I can do book events again. I enjoy meeting people, seeing friends, and making new friends.

Brown: What makes you roll your eyes when you hear/see it?

Spillers: 1. Reality TV for one. 2. Also opinion shows masquerading as “news” programs. Panels on “news” segments are chosen to present extreme views instead of reasonable, thoughtful discussions of policy issues and real news. The shows are meant to incite strong emotions in viewers, keep a loyal viewership and thereby attract advertisers. The hosts of some shows simply play a role and pretend to hold strong views they don’t actually believe. 3. Misleading social media posts on the right and the left that are clearly part of covert disinformation operations meant to incite and divide people.

Brown: To what do you attribute the biggest successes in your life?

Spillers: People.

Authors: As a writer I’ve been helped by friends who are also generous authors, including John Hailman, Tom Dawson, Ace Atkins, and others. John was a great help on “Confessions of An Undercover Agent” and Tom helped tremendously on “Whirlwind” and is helping me on the sequel. Ace is a national treasure and a mentor. He’s popular nationwide and HBO is producing a series based on his books. He’s a legendary writer, a great role model for other writers, and an even finer person who is generous with his time and advice.

Readers: I’ve been overwhelmed by the response of readers. They come in large numbers to book events, generously post reviews of my books on Amazon and Goodreads, comment online and send me messages, emails, and texts. Many dozens have posted and continue to post pictures of the book covers on social media. I’ve been amazed at the kindness of readers. We’re also blessed to have wonderful independent bookstores in the state, more than surrounding states, and one of the best annual state book festivals in the nation. Square Books in Oxford is nationally renowned at the best independent bookstore in the country, Lemuria in Jackson is a jewel, as is Book Mart & Cafe in Starkville, Turnrow Books in Greenwood, Reed’s Gumtree Books in Tupelo, and others. They do a fantastic job of connecting readers and authors at book events.

My careers in law enforcement and as a federal prosecutor were helped by a great many people, too many to name individually. Many great professionals and friends with MBN, the Baton Rouge Police Department, the U.S. Attorney’s Office, the Department of Justice, the State Department, DOJ Rule of Law in Iraq, the Regime Crimes Liaison Office in Iraq, the FBI, DEA, Customs, IRS, ATF, DOD CID, US Marshals, Secret Service, MHP, MBI and countless city, county and state law enforcement officers and leaders.

I’ve been blessed to know and to have worked with many extraordinary people. My successes in life have come from all those good people, and from the support of family and friends.

As I’ve noted, the Marines instilled a key ingredient: the mindset that nothing is impossible, and that ‘can do’ attitude has served me well. It’s not a chest-thumping spirit, but one that says quietly, “I can do this. I will get it done.”

Brown: What are some of the events in your life that made you who you are?

Spillers: “I am a part of all that I have met.” Alfred Lord Tennyson

Childhood formed me, Vietnam forged me, undercover sharpened the steel and the mind, being a prosecutor honed critical analysis and thinking, Iraq refined an international understanding, and writing revealed a life filled with extraordinary people and countless friends.

Brown: What would you like us to know about Charlie Spillers?

Spillers: Please let me offer a few thoughts.

1. Despite fighting in a war and a life working on criminals and mass murderers, I see a world filled with goodness and kindness. We are surrounded by everyday heroes.

2. People are fascinating. Nearly everyone has an interesting story to tell.

3. Mississippi cartoonist and author Marshall Ramsey once said in an interview that he can walk into a room and sense how people feel. That struck me because I’ve always been able to sense how people feel, even when they’re trying to hide it. Perhaps that comes from many years of working undercover where survival and success could depend on reading people.

4. I love dogs, I’m good at washing dishes and I make great spaghetti.

5. I love to read books that are so enjoyable that as I near the end I slow down to make it last. As a writer I try to create that same joy for readers.

Brown: What factors did you consider when you chose to live in Oxford?

Spillers: Fortunately, the Mississippi Bureau of Narcotics (MBN) chose Oxford for us.

I was promoted to be the MBN Regional Commander for North Mississippi and the office was in Oxford. So, in 1980 we moved from Tupelo to Oxford. My wife Evelyn cried for the first six months because we had moved to such a small, tiny town. It was a sleepy Southern village then, had few restaurants and was much smaller than it is now. She was used to Baton Rouge, Jackson, the Gulf Coast and Tupelo. But, as she has told many people, after the first six months you couldn’t pry her away from Oxford. She went to work for Ole Miss in the Housing Department and later in Planning and Institutional Research, and then had a great career as a Realtor/Broker.

When I was with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Oxford, the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the U.S. Virgin Islands asked me to transfer there and I agreed. I had visited St. Thomas on a port call when I was in the Marines and was impressed by the beautiful beaches, palm trees and crystal blue green water; it was a paradise. But a few days before we were to board a plane for St. Thomas, I changed my mind about the transfer. The quality of life is too good in Oxford. We’re blessed that our son and grandchildren live here.

Brown: How did you and your wife Evelyn meet?

Spillers: We met on a blind date. While I was in the Marines stationed at Camp Lejeune, NC, I went to Carolina Beach one weekend with buddies and met a family from Thomasville, NC. Their little girl, Mary Helen, took a liking to me and the family invited me to visit. I did, and they arranged a blind date with Evelyn. After our date she confided to her mother that I was not only a Marine but also a Catholic. “Well, it’s not like you’re going to marry him,” her mother said. We dated several times during future visits and then I left for Vietnam. We wrote and when I returned, we became engaged and married several months later. Fortunately, Evelyn’s mother was wrong.

Brown: Tell us about your children/grandchildren.

Spillers: Our son, Terry Spillers, followed in my footsteps and joined the Mississippi

Bureau of Narcotics and rose to the rank of Captain. He recently retired and now serves as a court security officer at the federal courthouse. His wife Brinkley is an attorney who works for the federal judges.

We’re blessed with four wonderful grandchildren: Michaela, 21; Hannah 19; Hoover Bennett, aka “Bud,” 3’; and Ella Kate, 2 months old. Those who have grandchildren know that they change your lives and open your heart to a special kind of devotion and love.

Grandchildren also change your mind to mush. When Michaela was only four months old, she was just beginning to make baby sounds. When I came home from work one day Evelyn told me she had just seen Michaela. I stopped in my tracks and asked, “Did she say anything?” Evelyn said, “She said ‘Gah.’” “Oh,” I said, amazed and excited. “How did she say it?” I seriously wanted Evelyn to say the baby sound like Michaela did. They change your mind to mush.

Brown: What do you do to improve your mood when you are in a bad mood?

Spillers: I exercise vigorously; it’s a great stress reliever and good for any mood.

Brown: What are you passionate about?

Spillers: I’ve always been passionate about my work. During my careers I devoted myself to mastering my job and doing the best I could. Now I’m passionate about writing as a profession.

I fill notebooks with examples of how other authors use dialogue, description, and scenes. I recently learned that some writers I admire keep similar notebooks and call them “Commonplace Journals.” I don’t refer to them when writing but writing something down helps ingrain it. I recall a study which concluded that for memory purposes, writing something is equivalent to repeating it out loud 10 or 11 times. That process served me well in my other careers and now it’s helping me hone my writing skills.

Brown: What’s left on your “bucket list?”

Spillers: If I had a bucket list it probably would have been empty long ago, especially of anything exciting. However, Evelyn enjoyed visiting New England with a friend while I was in Iraq and would love to go back, so that’s on the list. We have friends we would love to visit in Malibu, Hawaii, Washington, D.C., and Wyoming, and maybe visit a nephew who lives in Geneva.

Brown: To quote Katherine Meadowcroft, Cultural activist, and writer, “What one leaves behind is the quality of one’s life, the summation of the choices and actions one makes in this life, our spiritual and moral values.” What is your legacy?

Spillers: This is another quote that applies to leaving a legacy.

“Our souls are not hungry for fame, comfort, wealth, or power. Our souls are hungry for meaning, . . . to live so that our lives matter, so that the world will be at least a little bit different for our having passed through it.”

Living a Life That Matters, by Harold Kushner.

During my careers in law enforcement and as a federal prosecutor I worked with hundreds of officers, investigators, agents, and prosecutors. I taught in the graduate criminal justice program at Ole Miss, and served as an instructor in academies, seminars, and training conferences. I also served as instructor at the DOJ National Advocacy Center at the University of South Carolina, training new federal prosecutors. Hopefully, I helped influence the profession and reinforced our values of professionalism, integrity, and compassion.

On a personal level, I hope I inspired others by a “can do” spirit, and with the importance of constantly learning and striving. And with an occasional reminder that kindness is contagious.

Bonnie Brown is a retired staff member of the University of Mississippi. She most recently served as Mentoring Coordinator for the Ole Miss Women’s Council for Philanthropy. For questions or comments, email her at bbrown@olemiss.edu.