*Editor’s Note: The latest interview in the Ole Miss Retirees features is Dr. Ben McClelland. The organization’s mission is to enable all of the university’s faculty and staff retirees to maintain and promote a close association with the university. It is the goal of the Ole Miss Faculty/Staff Retirees Association to maintain communication by providing opportunities to attend and participate in events and presentations.

Dr. Ben McClelland may have grown up in Pennsylvania, but he found his niche at Ole Miss. His interview visit which included Square Books, Rowan Oak, The Hoka, and Taylor Grocery sealed the deal that framed his successful career here.

Brown: I know you grew up in Masontown, Pennsylvania. What is special about the place where you grew up?

McClelland: Located about seventy miles south of Pittsburgh and twenty miles north of Morgantown, West Virginia, my southwestern Pennsylvania hometown, Masontown, has a long history, including battles of the French and Indian War. During my early childhood, this town of 5,000 people was a hub of the soft coal industry—producing coke for steel mills—brimming with civic pride. It was the perfect small town for my buddies and me to ride our bikes, play pick-up ballgames, and hike in the surrounding woods. As kids we enjoyed traveling carnivals, circuses, and Memorial Day parades. By the time I was a high schooler, however, the coal boom was slowly but inexorably going bust, turning Masontown into a quiet hamlet and, some years later, a grim and economically depleted area.

Brown: Please talk about your parents, siblings and any crazy aunts and uncles.

McClelland: My mother’s prominent family headlined a cast of characters, including war heroes, town leaders, businessmen and—most of all—talented educators. And, of course, we had a black sheep or two and several raconteurs and practical jokesters.

My mother, the only girl with three brothers, had a streak of perseverance that enabled her to carry on in difficult circumstances from young adulthood onward. My father, who left college to join the Army, was captured at the Battle of the Bulge and subsequently killed in an allied air raid on an unmarked German POW camp.

My mother raised my older brother, my twin sister and me with my grandparents’ help and in her childhood home. My industrious grandfather, R. K. Wright, who had built a successful car dealership, was the borough president for decades. He was also an influential political operative in the region. My Welsh grandmother had grown up with her mother and two sisters running a boarding house for miners. She handily managed our large household and was fiercely proud of her family. Mother taught school for several years and then became the first female postmaster in our area. And she succeeded in holding the longest tenure of any local postmaster—even though she faced severe, years-long scrutiny from postal inspectors, who doubted that a woman could handle such a demanding job.

Benjamin Franklin Wright, my namesake uncle, had a great deal of influence on my upbringing. Like my father he left college to serve in WWII as a parachutist—the shortest jumper in the 101st airborne unit. If you’ve seen “Band of Brothers,” you saw my uncle in action. He participated in all of the major military campaigns in the European Theater of War, surviving when 80% of his fellow enlistees perished. He returned home with a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star, among other commendations—and a heart filled with survivor’s guilt. A skilled attorney, he taught me so much as a compassionate uncle—everything from camping in the wilderness to Morse Code to public speaking and the love of reading war histories (from the American Civil War to WWII).

Brown: What’s the most important lesson you learned from your parents?

McClelland: I struggle to name “the most important lesson” from the many that my family taught me. Knowing who I am, remembering the heritage, culture, and strength of character that they instilled in me, gives me an enduring sense of identity. Facing an entirely different world from that of my forebears, I have their constancy of values to help me contend with its challenges and vicissitudes. Even though I may be quite different from them in my institutional affiliations, I am definitely “of” them, even if not “like” them.

Brown: When you were a kid and someone asked you what you wanted to be when you grew up, how did you respond?

McClelland: The summer after my fourth grade in school, I began working as a grease monkey in our family automobile business. I wore a yellow and green, plastic Valvoline cap, the one shaped like a soldier’s cloth cap. I draped a red grease rag out of my back pants pocket, trailing the odor of dirty oil and grime. In this job I left the domestic confines of my grandmother’s kitchen and was introduced to a male-dominated world in the repair shop where everyone swore a blue streak. Thirty-year-old Jimmy, a soft-spoken, three-hundred-pounder with bug eyes and double chins lost his temper often, seething with barely audible cusses. Short hothead Danny often sent tools clanging across the cement floor while unleashing a stream of epithets. His young son—also Danny, also a hothead—would stand toe-to-toe with his dad, spewing blasphemous profanity. In this brave new world, I saw men vent rage and wield power over others through a bizarre new language. Of all these irreverent men, I worshipped the Tower of Babel, Crocky, the parts man. A wiry little guy, he was also the gas pump attendant—and the undisputed king of invective. Full of feisty charm and brash irreverence, Crocky whittled more privileged men down to his size. With his cunning use of vituperative words, Crocky was my hero. I wanted to be like him. One evening I used one of these treasured words in my mother’s presence. In fact, showing off, I called her by a crude and offensive term and told her, swaggering in my newfound power, that I wanted to talk like Crocky. Well, you can guess the end of this episode of youthful derring-do. My mother and her oldest brother, a high school principal and a man of unimpeachable rectitude who brooked no nonsense, resolutely served up sure justice and let me know that “in no uncertain terms, young man” are we like the men in the repair shop. And one thing for certain, he told me sternly, is that we do not use such language. He emphasized each word with a pointed index finger slicing the air in front of my nose. Long story short, I no longer wanted to be a parts man. Eventually, seeing the role models of the teachers in my family—my mother, my aunt, and my uncle—as well as my own classroom teachers, teaching became my sole interest throughout my life.

Brown: Where did you go to school?

McClelland: Throughout grades one through eleven, I attended school in my hometown, Masontown. In my senior year, our class was bussed to a new regional high school—Albert Gallatin, which was built near Friendship Hill, the famous American politician’s historic home.

Brown: Talk about your high school experience. Did you play sports, join clubs?

McClelland: A super-focused student, I loved Latin, French, English, drama, and public speaking. I also was the play-by-play announcer at our school sports events. Showing a little bit of my family’s political bones, I served as the school’s first student body president and delivered a speech at the dedication of our school. Truth be told, my uncle Ben helped me write and memorize a speech that intoned the region’s history and garnered me the American Legion Award at graduation.

Brown: What was your favorite subject?

McClelland: Without a doubt English was my favorite subject. I fell in love with Faulkner’s stories of family honor, sacrifice, and tragedy. His complex, multi-layered plots and convoluted and prolix sentences mesmerized me. Many years later, as doctoral student, I wrote a dissertation on Faulkner’s fiction.

Brown: What was your very first job and what were your responsibilities and pay?

McClelland: As a ten-year-old, I was a grease monkey in the family automobile business. I followed my older brother in this job. Jack-of-all-trades, I washed cars, changed oil, pumped gas, worked in the parts room, ran errands to buy car parts, and swept out the entire shop at night. Our most exciting job was driving new and used cars out of the shop and parking them in the sales lot each morning and returning them inside at night. We earned ten cents an hour, religiously punching in and out of the time clock. A hamburger and a milkshake cost fifty cents at the uptown dairy bar and nothing felt better than buying them with your own hard-earned cash. (And you could play pinball for a dime!)

Brown: Tell us about your college experience.

McClelland: I graduated from Grove City College, a Presbyterian school with a conservative bent, but with a faculty dedicated to delivering a liberal arts education. As an English major I continued to nourish my love of Faulkner and I developed my writing abilities under keen tutelage from close readers and critical thinkers. On campus I enjoyed the Joe College life, particularly through membership and leadership in a local fraternity. I flourished on the proscenium, taking on seven major roles in eight semesters, including Christian in Cyrano de Bergerac, Sheridan Whiteside in The Man Who Came to Dinner, and Vanya in Uncle Vanya. However, it was my role in campus affairs—through representing my fraternity and serving as a dormitory counselor—that was my signal achievement. Through these activities I developed an effective working relationship with the Dean of Men, who—a year after my graduation—offered me my first job in the academy: Assistant Dean of Men and Instructor of English.

In graduate school at Indiana University I found that I could hold my own in class with graduates of the best universities in the country. There, I earned an M.A. and a Ph. D. in English.

Brown: What advice would you give to your 20-year-old self?

McClelland: I am somewhat skeptical of advice, given or sought. I realize now that, at twenty, I was seeking to become a man, even as I lacked a full understanding of manhood. After years of reflection I now understand myself as a twenty-year-old, someone still seriously troubled by my father’s absence throughout my life. As a result, I sometimes acted compulsively rather than rationally thinking through decisions. Please recall, also, that this was the 60s, a time of social and political upheaval all across the country, and especially on college campuses. I was fervently embroiled in current events. What advice would I give? “Slow down a bit. Step back. Reflect.” That would be my advice, but I don’t know that I would have been receptive to it at the time.

Brown: Did you have a mentor who influenced your career choice?

McClelland: A number of wonderful people pointed me toward a career in education. I’ll name three: in high school Marino Pierattini, my English and speech teacher, and Edith Magalotti, my math and French teacher; in college Patricia Ford, my English composition and Faulkner teacher. Each had taught me that learning is a way of life. Decades later when I published my first textbook, I dedicated it to them.

Brown: Tell us how/when your Ole Miss “story” began? What did you know about Ole Miss before you accepted a position here? Who hired you?

McClelland: I came to the University in 1986 after thirteen years in the professoriate. While I was teaching American literature at Rhode Island College, my chairman asked me to establish and direct a writing program, which I did. Newsweek ran a front-cover story titled, “Why Johnny Can’t Write” and higher education was challenged to address that learning deficit. To help me transition to the new field—composition and rhetoric—I attended two National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) postdoctoral summer seminars: at the University of Pittsburgh, in 1977, The Composing Process and at Carnegie-Mellon University, in 1984, Modern Rhetoric. My work in these two scholarly endeavors led to my first publications and introduced me to the cadre of national leaders in writing program administration.

After working a dozen years in Rhode Island, moving up through the faculty ranks and serving two terms as chair, plus a year as assistant to the Dean of Liberal Arts, I decided to look for another position.

Ole Miss was among a half dozen universities seeking to fill a newly endowed chair in English Composition. As I entered the job search, a colleague who worked in upstate New York encouraged me to seek out Ole Miss. This South Carolinian had visited the campus and she was very complimentary about it and Oxford. I knew next to nothing about either, but soon became enamored of both during my campus interview.

Evans and Betty Harrington, among many other English faculty members, were gracious and knowledgeable hosts during my visit. I recall browsing Square Books, touring Rowan Oak, wide-eyed, paying homage at Faulkner’s grave, and visiting the area’s many cultural sites, including the Hoka. At dusk one night the Harringtons drove me out of town in a southerly direction through rolling farmland to a tiny hamlet where the catfish dinners were renown. Walking up the steps of Taylor Catfish’s wide front porch, I stepped back in time and viewed a segment of Ole Miss culture graphically depicted on every wall.

An English faculty search committee recommended three candidates to Chancellor Turner, who offered me the position.

In midsummer, when I traveled to Oxford to begin my new job, I stayed with English colleague Colby Kullman—for two weeks—while searching for a home. As we became close friends over the years, I would come to know Colby as the embodiment of hospitality, welcoming numberless newcomers and visitors to Oxford and the University.

After a thirty-one-year tenure at the University, I retired in 2017.

Brown: You have written several books. Tell us about this.

McClelland: I engaged with colleagues across the country, who were creating a paradigm shift in teaching English composition, moving from product assessment to the composing process. My first co-edited collection of essays, published by the National Council of Teachers of English (1980), presented eight new instructional approaches to teaching writing. A second collection, published by the Modern Language Association (1985), presented thirteen essays that reviewed the major scholarship in a variety of fields that were shaping composition studies, including rhetoric, literary theory, cognitive studies, collaborative learning, and artificial-intelligence research. I also wrote two textbooks for freshman English classes: Writing Practice: A Rhetoric of the Writing Process, Longman, Inc. (1984) and The New American Rhetoric: A Multicultural Approach. New York: HarperCollins (1993). In addition, I contributed chapters to three books on writing theory and writing program administration.

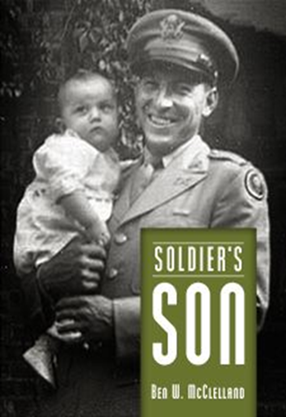

My next two publications came as a result of research and writing that I conducted during sabbatical leaves. In 2004 I turned to writing nonfiction with a memoir, Soldier’s Son, published by the University Press of Mississippi as a Willie Morris Book in Memoir and Biography. In this memoir of family stories, I seek to know my father, who was killed in WWII when I was an infant, and thus I seek to know myself.

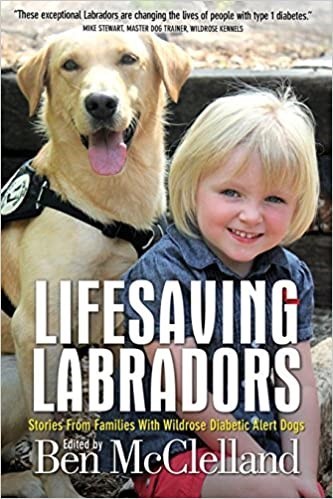

In 2014 Koehler Books published Lifesaving Labradors, a collection of stories I edited from families who use Labrador retrievers as medical assistants to alert Type 1 diabetics to dangerous blood sugar changes. In the process of researching and developing this book I immersed myself in the subject, joining the Wildrose Kennels training staff for a year and learning how to train retrievers, as well as interviewing the diabetics’ families then and in ensuing years to develop their stories.

Brown: What was the most rewarding/most challenging of your responsibilities?

McClelland: Developing the multiple activities within the UM Writing Program brought great rewards: The Writing Project trained master teachers and conducted innovative teacher training for high school teachers. Working with north Mississippi school districts—and talented masters teachers, such as Anna Quinn, Nell Green, Cathy Stewart, Susan McClelland, and Jane Talbert—we launched and sustained professional development programs, offering hundreds of teachers training in new writing pedagogies. On campus Mary Ann Bowen efficiently managed the logistics of our many training sessions in Alumni Center. Over the years many of UM’s academic administrators served to nurture this work.

On campus, the enhanced Writing Center supported all of our student writers. UM personnel, including Deborah Pope Kehoe, Linda Spargo, and Brenda Robertson were central in launching this effort. With a major acquisition of computer technology, along with developing a trained peer tutoring staff, we assisted hundreds of student writers a semester, especially those in first-year courses. However, the Writing Center also served upper class and graduate students.

New teacher training activities enabled the English Teaching Assistants to adopt a new pedagogy and deliver instruction to undergraduates in all of our beginning English classes. Teaching assistants also benefitted from gaining this new pedagogical training because they could demonstrate a new professional skill to potential employers. Bob Cummings, a stellar UM graduate student instructor of that era, would return to campus after a hiatus elsewhere to reboot writing instruction in a program that would evolve into the Department of Writing and Rhetoric, which is now ably directed by Stephen Monroe.

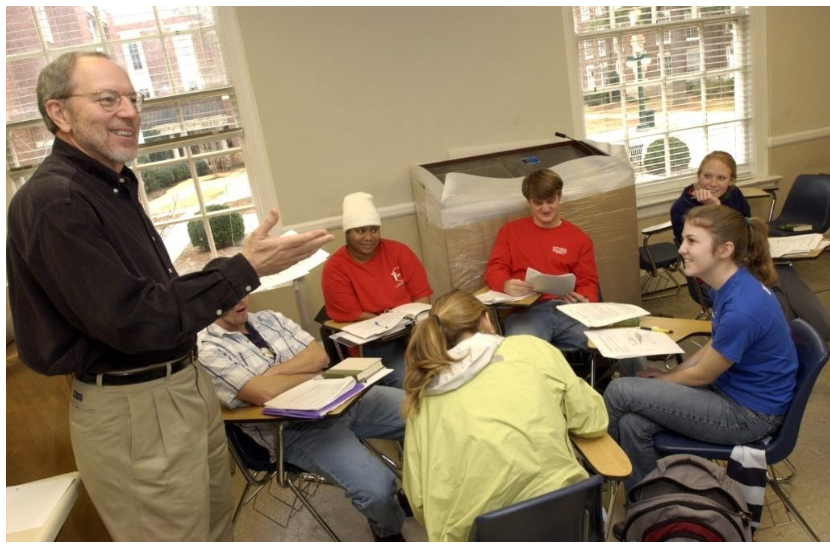

Working with student writers in undergraduate and graduate writing workshops demanded most of my time and expertise, day-in and day-out. The challenge for me was always to be able to read and respond to student writing in order to empower the student to develop as a thinker and writer. When students achieved surprising epiphanies, we felt a rush of delight. Undoubtedly, the most rewarding engagements I had in the reading and writing process were with students’ reflective work on their personal experiences. Working on yearlong senior theses with students resulted in some of the finest writing products I recall.

Brown: What accomplishment are you most proud of to date?

McClelland: My decade of service on the Executive Committee of Council of Writing Program Administrators (1982-1992) enabled me to participate at a national level to establish guidelines for, offer consultation to, and make evaluations of college and university writing programs and their faculty and administrators. During that time, I served in several roles: editor of the journal, director of the Board of Consultant-Evaluators, Vice President, and President. As a consultant-evaluator, I assessed writing programs at over a dozen colleges and universities and wrote reports for their academic administrators. I am pleased to have served actively during this seminal time in the formation of writing programs in American higher education.

Also, being founding director of the grant-funded UM Writing Project, I was able—for a dozen years—to bring in educational experts and offer innovative professional development to UM’s freshman English instructors and to north Mississippi’s public school teachers.

Brown: If your life were a book, what would the title be?

McClelland: Damn Yankee. I’m a Northerner who came to reside here because I not only found a place and a career that I loved, but also a life partner, who is a consummate professional educator. My wife, Susan, UM Professor and Chair of Teacher Education, and I have enjoyed raising a family and working as colleagues for nearly three decades.

Purchasing the former home of Patricia Brown Young at Pea Ridge was a highlight for us. We enjoyed country living just a few miles from the Square and made warm friendships with our neighbors, including Debra Young, whose restored cabin was next door. During this time son Ryan matriculated to the Honors College at the University, graduating as the Taylor Medalist in English in 2002. Daughter Brooke opted for the small-school experience, excelling in music and Spanish at Rhodes College, where she graduated with honors in 2005.

Early on in our Ole Miss story Susan, who was an English teacher and an assistant principal at Oxford High School, was invited to be the first woman high school principal in nearby New Albany. We moved and resided there for a dozen wonderful years, making lasting friendships with neighbors and friends. During that period, we raised son Kevin and our younger daughter, Kellie, with a gaggle of church and school friends. Kevin played the tuba in the band and played football and soccer, graduating in 2002. Kellie played the flute in the band and was a cheerleader and power lifter, graduating in 2012 and entering the Honors College at the University.

Over time Susan moved to up to serve in the school’s Central Administrative Offices. And, then, folks at UM’s School of Education, including Tom Burnham and Andy Mullins, invited Susan to join them in directing the Mississippi Principal Corps. After Kellie’s high graduation and subsequent enrollment at the University, we resumed our residence in Oxford.

When Kellie graduated with honors in English from Ole Miss, I was honored to present her undergraduate diploma to her. Taking the alternate educational route, she also earned a master’s in education through the Mississippi Teacher Corps. At Kellie’s graduation ceremonies Susan had the honor of handing her master’s diploma to her. Kellie has also become an English educator, beginning her fourth year as a dedicated public-school teacher in Mississippi.

Brown: Tell us about your “lifesaving Labradors” and your affiliation with Wildrose Kennels. What has been your routine since retirement? Do you have any hobbies?

McClelland: Wildrose Kennels is a premier breeder and trainer of British Labradors. I became affiliated with Mike and Cathy Stewart’s thriving business operation in 2011 as I apprenticed as a gundog trainer. During my year there and a couple of subsequent years, I also became associated with the Service Dog Program, through which families of Type 1 Diabetics acquired Wildrose Labradors to assist in managing the sudden and sometimes very dangerous shifts of sugar in the diabetic’s blood. Because of their exceptionally keen olfactory senses, the dogs can be trained to sense sugar level changes in the blood. Even though computer sensors can be used for this function, the dogs reliably alert to changes as much as twenty minutes before a monitor registers them. This permits caretakers to make sooner interventions. Many of the families called their dogs “lifesavers” because they literally helped the families’ diabetics avert disastrous blood sugar level drops—often waking them during the night when everyone was sleeping. This medical service work is not without serious challenges, however, usually requiring significant dedication to dog training and obedience, as well as continuously guarding against human interference with the dogs’ work.

My relationship with Wildrose Kennels led to a hobby of raising and training British Labradors for upland and waterfowl retrieving. Over the last nine years I have raised and trained four labs from the age of seven weeks. In my retirement this hobby morphed into a fulltime avocation. My wife and I now have a kennel—dubbed Hopewell Kennels—with five Wildrose Labs, three females and two males, ranging in age from 12 to 1 ½ years old. Their roles range from mating, to field and water retrieving, and to serving as a Therapy Dog.

Brown: Do you have a favorite quote? What is it and why is it your favorite?

McClelland: I have a number of favorite quotes. Here are a couple of them:

“What, after all, is history if not the words handed down through remembrance and kindred blood?” Willie Morris, Homecomings.

This is the headnote for my family memoir, which I wrote using the stories handed down to me by my forbears.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun.

For me this succinct bit of wisdom encapsulates the complex interweaving and intersecting of the past in our present lives—something that I experience every day.

Brown: What’s your favorite way to waste time?

McClelland: Not fond of wasting time, I busy myself daily with ambitious “to-do” lists.

Brown: Where’s your favorite vacation destination and why is it your favorite?

McClelland: For seventeen summers (from the late seventies to the early nineties) our family spent our Julys on Martha’s Vineyard, where I taught new writing pedagogy to teachers. The “Vinyud” offers so many varied opportunities—biking, sunbathing and walking beaches, sightseeing, fishing and boating. Great small towns from upscale to down home dot the island. It features restaurants galore and a great farmer’s market. Our family enjoyed hanging out on the spacious deck of our secluded house and spending fun hours on the beach. During breaks from our body surfing and swimming in the cold Atlantic waters we lunched and snacked from our picnic basket and cooler. The Vineyard Haven Street Fair was always a highlight. We strolled through town with the festive crowd, chowing down on lobster rolls and finishing the day with tall cones of Mad Martha’s ice cream. We enjoyed spotting celebrities, such as Carly Simon and Jackie Onassis. We even made acquaintances with William Styron, Richard Dreyfuss and Art Buchwald.

Brown: What are some things that you have marked off your bucket list?

McClelland: Two travel adventures: My wife and I took a marvelous, two-week cruise with friends, touring the Greek Isles, Baltic capitals, and St. Petersburg, Russia. Our family also took a leisurely summer road trip to the American West—with mother-in-law, daughter, and grandkids all aboard. On that trip the journey was as much fun as the destination, as we toured quintessentially American sights en route, including the Black Hills, Mount Rushmore, Wall Drugs, the Crazy Horse Memorial, Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, and Yellowstone National Park.

Other family projects that we have launched during my retirement:

In the early spring of 2020, Susan and I set up two, raised-bed gardens in our backyard. We planted tomatoes, peppers, green beans, okra, basil, and cilantro. Now we’re enjoying the fruits of our labor. Also, in June we started a backyard chicken flock. We purchased a variety of eight, day-old chicks and raised them in a homemade brooder inside our garage for six weeks. We also built a henhouse and a wire-covered run next to our dog kennel. When the chicks were six weeks old, we moved them to their outdoor quarters. Some months hence we’ll be collecting eggs. For now, we are entertained watching their antics. Yes, we named them. They’re family, after all—outdoor family, that is.

Brown: What three words best describe you?

McClelland: Self-starter, humorous, reflective

Brown: To quote Katherine Meadowcroft, Cultural activist and writer, “What one leaves behind is the quality of one’s life, the summation of the choices and actions one makes in this life, our spiritual and moral values.” What is your legacy?

McClelland: My legacy lives in the students that I have empowered to become self-aware critical thinkers and effective writers, to become learners and innovators, and members of a compassionate human community.

Bonnie Brown is a retired staff member of the University of Mississippi. She most recently served as Mentoring Coordinator for the Ole Miss Women’s Council for Philanthropy. For questions or comments, email her at bbrown@olemiss.edu.