Contributors

Bonnie Brown: Q&A with Ole Miss Retiree Dr. Jim Payne

*Editor’s Note: The latest interview in the Ole Miss Retirees features is Dr. Jim Payne. The organization’s mission is to enable all of the university’s faculty and staff retirees to maintain and promote a close association with the university. It is the goal of the Ole Miss Faculty/Staff Retirees Association to maintain communication by providing opportunities to attend and participate in events and presentations.

Whenever you encounter Dr. Jim Payne, you will see a smile and an enthusiastic greeting. He embraces life with optimism and humor. He continues to reinvent himself and he has a terrific story to share.

Brown: Tell us about the town/city where you grew up. What is a special memory of that community?

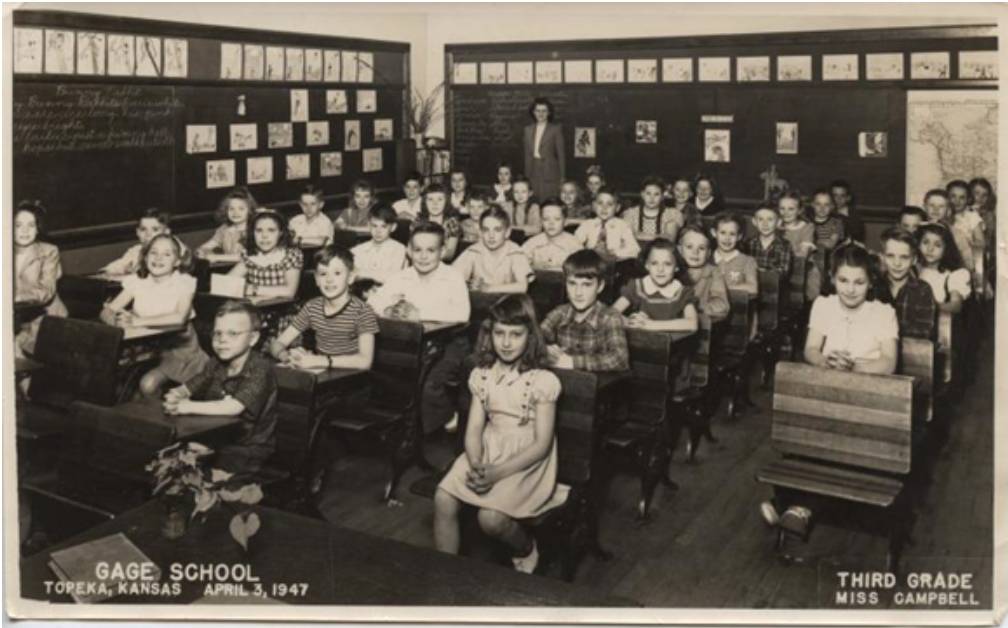

Payne: I was born in Topeka, Kansas, on the east side which was a predominantly Black neighborhood. During my first and second grades, I had tremendous trouble academically. When I finished second grade my parents move to the west side and I went to Gage Elementary School. The thing I remember most is about the grass—the grass on the west side was green where it was brown and patchy green on the east side! We were a half a block from a private tennis club that was palatial, and two blocks from Menninger Clinic, a famed psychiatric clinic for the rich and the famous. I can’t describe the grounds and the buildings and all, they were fabulous. I also remember that on the east side many of the windows on the houses had bars and on the west side they had screens. I was too young at the time to really understand that I was a minority.

Brown: Please talk about your childhood. What is your earliest memory?

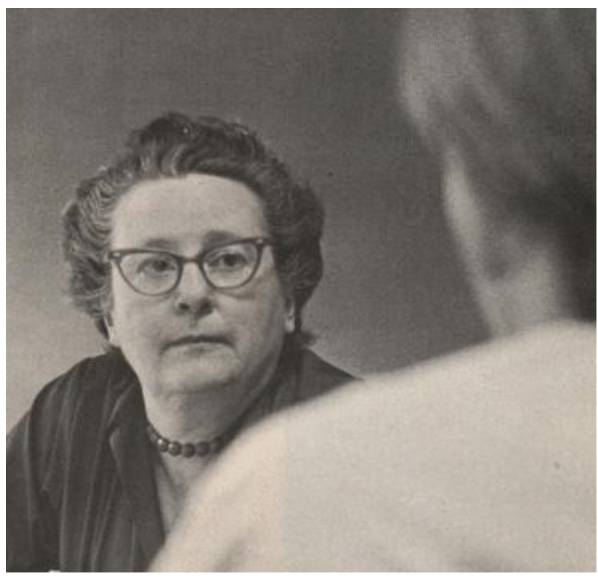

Payne: I had a great childhood, but I really struggled academically in school, always at the bottom—the very bottom—of the class. I remember that after we moved to the west side of town to Gage School, I failed the third grade. At the end of the year, my parents were called into the school and I can remember my third-grade teacher, Ms. Campbell. I can remember her wrinkled face, her rimless eyeglasses, her hair, her stooped shoulders. She wore a “wash woman’s” dress, dressed in flats—I can vividly see her to this day. We go to school and we go down to her room. She’s sitting behind her desk and she doesn’t get up to greet us but points to the chairs in front of her desk. My parents squeeze into the desks which were old wooden student desks that had “ink wells” in the desk (which were before my time). My dad is on the right and my mother is on the left. Ms. Campbell begins to explain that I was going to have to repeat third grade, which we knew. She also explained that I couldn’t read, which we also knew. Then she started saying some things that I did not know and that was that the reason I could not read was my parents’ fault! So, she lashes into my parents saying they’ve got to teach me, they’ve got to help me, they’ve got to work with me after school, they’ve got to do this, they’ve got to do that. And as she is speaking, I realize my parents were slackers! We finish. She thinks we finish, my mom thinks we finish, and before we can get up, my dad leans forward and says, “Ms. Campbell, look I don’t think you understand. We’re parents. And what parents do is they take their kids on picnics, they play catch, they fish, they hunt, they go to the movies, and they go get ice cream together. We’re good parents, we’re loving parents, we’re caring parents and we do those things. But if the student hasn’t learned, the teacher hasn’t taught. So, this next year why don’t we continue to be parents and why don’t you ratchet up your teaching ‘cause I know you don’t want him the third year.” She was stunned! Then my dad gets up, my mom gets up, and I get up, and we walk out of the room and start down the hall. We leave the building, we’re on the sidewalk, I’m holding my parents’ hands—my dad on the right and my mom on the left. I then ask where we’re going now. My dad said, “We’re going to get some ice cream.” And he said it in the tone of voice that I knew it was going to be a double-dip day. I had a strawberry on top, chocolate on the bottom in a cake cone and I savored every lick!

I really had a wonderful childhood. But when it came to schooling, it was a struggle. And I loved school, I never played hooky, I went every day, even when I was sick. I was in all the sports both elementary and high school. I had great friends. We played well together. But academically, I struggled.

My dad was a milkman back in the day when they delivered milk to your door. He had a wagon with horses, and he would get up every morning around 5 a.m. and he’d go in and would hitch up the horses and ice the wagon and fill it full of milk. They also had orange juice and grape juice. Then he would head out to deliver the milk. He had a third-grade education and worked as a milkman for 20-25 years. Then when grocery stores started carrying milk, they did away with the milkman. My dad was the last one to have a horse and a wagon, but in the last two years, he had a truck.

Then we moved to Sunflower, Kansas. We lived in Sunflower Village. He was a shift supervisor at a plant that made gun powder. We were there until they closed the plant down. When they closed the plant down, my dad was devastated and having only a third-grade education, he couldn’t get a job. He started drinking heavily and became an alcoholic. Because he couldn’t work, my mom who had been a stay-at-home housewife, who had never driven a car and had a sixth-grade education, went to work as a clerk in a dress shop called College and Career. The owner eventually sold the dress shop after my mother had worked there for three or four years and he bought a greeting card shop and she worked there. She sold cards then until she retired.

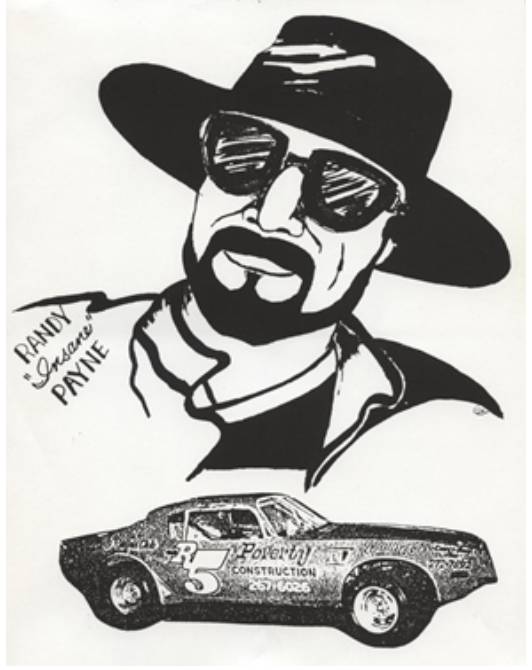

I have two brothers, both younger, with whom I am very close. We stay in touch. My younger brother Randy is very unusual—full of life—and people just love him. As a hobby, he raced cars every Friday night at an old track at Topeka Fairgrounds. He had sort of a fan club of about 25-30 people who would hang out and drink. He had a white jumpsuit and a white helmet. He started every race at the back of the pack. Then he would drive his car up until he got to second or third place. He never ever got to first place. He’d get to second or third place and then the car would blow up, or blow a tire, so he’d have to pull into the center of the track. He’d get out of the car and wave to the crowd. The people in the stands would go crazy. He got a bigger ovation than the winner of the race!

Soon after I came to Ole Miss as the dean, I got a call from my mother and she said you’ve got to get here, Randy’s in a lot of trouble. It was big trouble this time. So, I got in the car and drove to Topeka. He was in jail. I asked what had happened and was told that he had tried to rob the bank. I go to the police station and told them who I was. Everyone knew Randy, he had a long record of speeding tickets, drunk driving. I asked what had happened and was told that he and his buddies were drinking at his house. They were watching TV and there was a cowboy movie on where they robbed a bank. He thought it would be interesting if he went down and robbed the bank. He tried to get his buddies to go with him, but they went home instead. So Randy is at home by himself with his dog named Savage. Randy gets his shotgun and puts a bandana around Savage’s nose, then one around his nose, and drives down to the bank. My brother has long hair and is lanky, and easily identified. He goes into the bank, the dog stays in the car. He walks into the bank and announces that this is a stick-up. The people in the bank all know him and tell him to go home. He declares that this is a real stick-up and fires off a round into the ceiling. When the police are on the way, he hears the siren and jumps into his car with his dog Savage and starts driving. The policemen said they couldn’t catch him, that they had every police car in Topeka, Kansas, trying to catch him, something akin to the O.J. Simpson chase. He was, however, stopped by the tree he hit, resulting in a broken arm and bruises. However, he declared that Savage was unharmed! He went to prison at Leavenworth, then was transferred to Missouri for a year. When he was due to be released, he didn’t want to leave. He liked prison life! When he was released, he purposely neglected to see his parole officer and was sent back to prison. He’s been incarcerated four times. He now lives with his daughter.

Brown: What were you really into when you were a kid?

Payne: I was groomed to be a professional baseball player. When my dad would come home from the milk route, every day we would go down to the ballpark. He’d throw balls and I’d hit them. We had 24 balls. So, I’d hit them, then he’d go out and pick them up and he’d have a bat and hit them back to me, so I’d catch them. We did this every day. I remember that he made a wooden case and painted it red. It held the 24 balls. We hit the balls so much that they would tear along the seam. My dad would sew the balls back up because we couldn’t afford to buy new balls.

In the area where I was, I was always one of the top hitters, ranking in the top 3 or 5 spots, whether it was in high school or college, Elks Club, Legion ball, made no difference, I was always in the top 3 in terms of hitting average. I was six feet tall and weighed 155 pounds but wasn’t very strong. I couldn’t hit the ball far, but I didn’t strikeout.

I had an opportunity to go to a training camp in Florida. When I arrived, I look at these other players and while I thought I was good, their arms were as big as my thighs! They had no necks. When we showered, they had hair on their backs. And I’m not sure if I should say this, but I was standing at the urinal, and a player came up to the urinal next to me and was urinating with such pressure that his urine splashed out on me. At that point, I went over and washed off, packed up my clothes, and came home. I later found out they were going to send me to the Chattanooga Lookouts in Tennessee, but I never went back. I have, however, been truly fortunate to have been supported throughout my life. There has always been someone there that has encouraged me, taught me. It’s meant everything to me. I have been so blessed.

Brown: How did you respond when asked as a child what you wanted to be when you grew up?

Payne: I wanted to be a coal man. In those days, the coal man would come in a truck with coal in the back and he’d shovel it into a bucket. He’d bring it in and deposit it into the container or a place outside the house. My mother would ask me often, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” My response was always a coal man. In looking back on it, what thrilled me about being a coalman was when you’re poor, in the winter, heat is important. So, this coal provided heat. I saw the coal man as a person that really had an important job and he delivered coal that was very important to our livelihood. The second thing was that he was dirty. I mean he was covered in black dust and I thought that has to be the greatest job in the world. You provide a great service and you don’t have to take a bath. I had that desire probably up until I went to high school.

Brown: What world events were significant to you growing up?

Payne: I vividly recall when a law was passed integrating the restaurants. At the time, I was managing a restaurant in Topeka, Kansas, called Allen’s Drive-In. All my employees were white. Prior to that, there were signs “colored served in sacks.” I can remember when I went to Dodge City Junior College, there were four of us who had baseball scholarships. We would drive across the state from Topeka to Dodge City about four times a year. I didn’t have a car. Only one of the Black players had a car. When it came time to eat, I would have to go in and get the food and bring it out. We’d eat in the car. It was hard to find a bathroom too. Every trip, we would be stopped, and they would ask who we were, where we were going. To be honest, I’d never really thought about it until we integrated the restaurants. I broke it down into 3 sessions or types of training in my role as manager. 1) Get people served; 2) Get them served civilly; 3) Try to change opinion and embrace diversity. It had a huge impact on my life. I’m somewhat embarrassed. I was born in the Black section of town, moved to the white section, played baseball and every team I played on was mixed. I never really understood the Black issue until the integration of the restaurants.

Brown: What was your very first job? What were your responsibilities and what was your pay?

Payne: When I was a freshman in high school, I was a “soda jerk” at Sunflower Drug Store in Sunflower, Kansas. I think my pay was 20 or 25 cents per hour. My job was to draw drinks, make floats, sundaes, sodas. In those days, Cokes were made with syrup; you put it in a glass and added fizz water and stirred it. Of course, floats, sundaes, and sodas were done the same way. I loved wearing the paper hat that all soda jerks wore. I just loved it! I can remember going to work and putting the hat on when I left the house, and wearing it all the way to work, then during work, and all the way home where I removed it and laid it on my dresser. For some reason, I just loved that hat.

Brown: Talk about your high school experience.

Payne: I continued to struggle academically although I loved high school and went every day. I remained at the bottom of the class academically in every single class. I fell in love in high school and married my high school sweetheart, Ruth Ann, after dating seven or eight years. She also came here to Oxford with me and was the counselor at Oxford High School. Ruth Ann and I were married 36 years and she passed away from cancer. I went through some real depression.

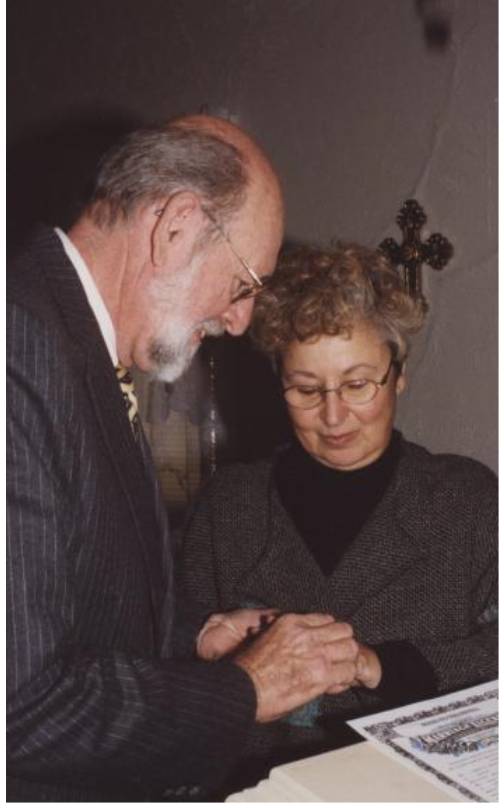

I had no plans to date or remarry but across the hall from me was Esim Erdim (from Turkey) and we married. After the deanship, I got a Fullbright and taught in Turkey for a year. I learned a lot about the culture. I had never really been outside the United States. We’ve been married 19 years. I have been blessed to have two great marriages.

The way I was able to go on to college because there was no ACT or standardized test and if you had a high school diploma, you could go to college. And after high school, you really had only two choices: you went to college or you were drafted. I chose to go to college although I was woefully unequipped to go to college, and of course in college, I just struggled. But I loved high school.

Brown: What was college life like for you?

Payne: Truthfully, I went to college primarily to play baseball and get out of the draft. Remember that I can’t read, not even a newspaper, and still have difficulty reading today. I failed my first year at Washburn University, then I went to Dodge City Junior College. I got a scholarship, oddly enough, even though academically I was terrible. The scholarship paid for my expenses and my room. They allowed me to work at the Lariat Café as a busboy and I got to eat there free. I stayed in the Dodge City Firehouse next to Boot Hill, the famous cemetery and museum, and was so close, I could lean out my window and drop a pebble into the cemetery. I got my Associates’s degree, then I went back for my junior year at Washburn. The thing that changed my life was my English teacher, Ms. Southworth. There were no tests to get you in or out, but they had tracking.

Of course, I was at the bottom of the track. I had tested so low on the English proficiency test that I was in the lowest track. Ms. Southworth came into class and the first thing she announces to the twenty-some students in the class, “I want to make this perfectly clear that this is referred to as ‘bonehead English.’ The reason it’s called ‘bonehead’ is that you’re boneheads. You scored so low on the English test that people have given up on you. They don’t think you’re going to get through it. I’ve got one goal in life and that is to pound enough English into your head, so you’ll pass the English test when you graduate.” That was her introduction. She pounded away! She had a rule that if you had 3-5 misspelled words, you’d get an automatic F. I get halfway through the semester and I’ve got F’s on every project. I go to her office, pound on her door, and she said “It’s unlocked, come on in.” She’s sitting there among these piles of paper. I started to introduce myself, but she interrupted by saying “I know who you are. You’re in my third-hour bonehead English class. What do you want?” I reminded her that she said she was going to pound enough English in our heads that we would pass the English proficiency test when we graduate, and I don’t think I’m going to graduate. I’ve had all F’s. She said “I’ve had my eye on you. You can’t spell. Get a dictionary.” I said “Well, I’ve got a dictionary but how are you going to find the word if you can’t spell?” She said, “Stand up. Turn sideways. Let me see your back.” I did so and she told me that “you are a good looking young man and to go over to the Student Union and walk up and down and find somebody over there, probably a co-ed, that’s got books piled around her. Then you ask to sit down and ask her if you can buy her a Coke. Then run—don’t walk–get the Coke, bring it back and you explain to her that you’re in an English class, that you’re having trouble and you need somebody to proof your papers to help you with the spelling. But don’t use the word bonehead!”

A few days later, I went to class. At that time, they didn’t have printers or copy machines, but they had mimeograph machines. Ms. Southworth had re-done my paper and removed my name. She handed it out to every student. She said I want you to read this paper, it’s got something in it that none of the other papers had. I’m thinking oh my gosh! So, finally, the class finished reading it and the guy in the front row raises his hand and says it has more than 5 spelling errors. She said she knew that, but she was talking about something positive. Everybody is looking quizzically and re-reads the paper. Nobody can get what’s positive. Ms. Southworth then tells the class that this paper has style. After you read the first two sentences, you can’t put it down. After you read the first paragraph, you have to get to the second paragraph. This has style! I didn’t even know what “style” was, but I knew I had it. That then changed my life to think that I could write. That, of course, lead to my publishing thirty books, three of which are the largest-selling texts in my field of special education. I’ve had three books presented at BookExpo America. I’ve had a good career in writing—but I still can’t read! I’m very good on style and good on continuity and flow. But academically, Ruth Ann proofed all the papers and now Esim proofs all my papers to this day. It’s been quite an experience.

Brown: Tell us how/when your Ole Miss “story” began? Who hired you? What was the interview process like? How long did you work at Ole Miss?

Payne: I have vivid memories of this because I was at the University of Virginia from 1970-1985. I had written my best-selling books, I was making a lot of money in royalties, I was doing consulting with Fortune 500 companies, and I also had a small consulting firm on the side. I was teaching the largest enrollment course at the University of Virginia. About my fourteenth year after advancing through the ranks of assistant, associate, and full professor, I was thinking about getting out of academia. I’d been offered a couple of jobs in business that would pay considerably more, and it would have been a different career path. Larry Tyler who I graduated with at the University of Kansas in special education came to Ole Miss in 1970 and he told me that there was an opening for the deanship at Ole Miss, and he wanted me to apply. I explained to him that I’d never held a chair’s position or administrative position in the University. But he said that I knew a lot about management, having been Director of Head Start, Director of the Wyandotte County School and Sheltered Workshop, you’ve consulted with Fortune 500 companies, etc. I said that I had but they are going to want someone who’s been a chair and maybe a dean somewhere else. He then suggested that I apply. He called me back again and he said just send me your vita and I’ll write the letter recommending you and you’ll be “in the hopper.” I sent the vita. The next thing I know they had a pool of 15 candidates. I was one of the 15. I came for the interview. At the time I was bald-headed, bearded, and all the administration here looked like they had stepped out of Vogue Magazine. They had suits that fit and shoes that were shined. I came in here and go through the interview process. I have a great time and left and told Ruth Ann that there was no way they are going to hire me. We don’t need to worry. So, I start making plans to leave and get into business and out of academia. Then I get called a second time and the pool had been reduced to 5. After that interview, I’m told by Larry Tyler that they are going to offer me the job. I then met with Chancellor R. Gerald Turner. Of course, you know what he’s dressed like, you know what he looks like, you know what I look like. As it ends up, he hires me, and I was the Dean for 10 years (1985-1995). I stayed another 25 years for a total of 35 years. I was at the University of Virginia for 15 years, so I’ve been a University Professor for 50 years! I still have trouble reading, still have dyslexia, and learning disability.

Brown: What did you know about Ole Miss before you accepted a position here?

Payne: I absolutely knew nothing, and I wasn’t interested in learning about the University. What I knew was that the State of Mississippi had the highest rate of illiteracy in the United States. So, what attracted me to Mississippi was their high rates in illiteracy, teen-aged pregnancies, and obesity. I was fascinated with the State, especially the Delta. I actually came here not because I wanted to be the Dean. I actually came here because I thought I could do something about illiteracy because I had (and still have) reading problems and I knew a lot about reading. I’ve helped a lot of kids learn how to read, I helped a lot of teachers learn how to teach reading, so I believed that when I came here that I could “move the needle” on illiteracy. Sadly, I haven’t moved it one iota. I’ve helped a lot of people, I’ve taught a lot of teachers how to teach reading, but I haven’t moved the needle and that’s been a frustration. I have new ideas that are much different than I think we could revolutionize public school education, which would make it more powerful and more effective in teaching children how to read, do math and science and the fine arts. While I have the ideas, I don’t think I’m going to get in a position to communicate those ideas. Although, I haven’t completely folded up yet.

Brown: What were some of your responsibilities?

Payne: I was not a good Dean. I didn’t know what deans did and I didn’t know what deans were supposed to do. I couldn’t have survived without Marjorie Douglass. She ran the School of Education and kept me on track, guided me, supported me. She was my Assistant and had been here with Syl Moorhead. She was really good. When I came to campus in 1985, the roof on the School of Education (the former high school) leaked, we couldn’t control the temperature, we didn’t have any audio-visual equipment that worked. We didn’t have an overhead projector that worked. We didn’t have a TV that worked. We had one computer, a Radio Shack, and it was in Marjorie’s office. I came on July 1, we started school in August. When we get to October, we ran out of paper. We did not have one ream of paper in the building and we had no money to buy paper. In November, they came in and took all the phones out of the School of Education, except one which was on Marjorie’s desk. If we had to make a call, we had to go to Marjorie’s office. We couldn’t pay the bill.

The big thing that happened that I won’t forget is Paul Hale (Director of the Physical Plant Department) called a meeting of all the building mayors who were responsible for the general maintenance of the various buildings to the Physical Plant Department boiler room. I didn’t know that the other deans had delegated the responsibilities of mayors to somebody else, so I was the Dean and the mayor. We met in the boiler room and it’s got three or four huge boilers/tanks, and the floor is cement and it’s dirty. There are cobwebs everywhere. All the mayors (and I’m the only dean there) sat in wooden, folding chairs and Paul Hale addresses us from a lectern that they must have gotten in a garage sale. It was pitiful. He begins to explain that if we have a severe winter, we will not have enough money for fuel to heat the buildings, so we need to come up with a contingency plan. Then he said that the boilers/furnace were purchased during the Civil War—then he hesitated, before saying “used!” I was shocked. I can’t remember what the contingency plan was. I walked out of there wondering what I had gotten myself involved in. We were poor as church mice in the School of Education, but I had such talented and dedicated faculty. What happened during the time that I was the Dean really didn’t have anything to do with me, but more with the faculty that kept rising to the occasion. They did phenomenal things. Jim Nichols, Director of Institutional Research, had developed a teaching faculty evaluation instrument (SPOT). He provided the results to all the deans, and the School of Education had the lowest ratings of all the schools. I took that information back to the faculty, not to be derogatory but just as information that had been provided at the meeting. They all said we could do better than that. They started focusing on teaching. Within three years, the faculty who had been at the very bottom were at the very top and stayed there until my tenure as dean ended. We did this in a variety of ways. One thing we found out was that a lot of the low-scoring evaluations were taught by graduate assistants. We didn’t teach the graduate assistants how to teach, we just threw them in the classroom and had them teach. I remember we had Human Growth and Development where we had 6 or 8 sessions every semester and the evaluations were at the very, very bottom. This was done in the Counseling Department. When Phil Cooker saw that, he said that he could take over that class, teach them in the auditorium all at once so we won’t have multiple sections and we’ll have 6 or 8 graduate assistants to assist other faculty. He took over and he is a tremendously gifted teacher. In one semester, we went from 6 or 8 classes receiving the very lowest evaluations, to one large class being the very highest. At the time, faculty were teaching 3 or 4 courses a semester. I came from Virginia where they were teaching 1 or 2 courses per semester. I looked at student enrollment here which was half what it was at Virginia, and the number of faculty we had here was half of what it was at Virginia. But the number of course offerings in the School of Education was twice what they had at Virginia. So, we were offering a lot of courses and requiring students to do a lot of stuff. What we did within one year, we got the faculty load down to 2 classes a semester which then gave them time to focus on the teaching and of course do scholarship, writing, and research. By my seventh year, a guy by the name of Rick Ittenbach did a study of the faculty and one-fourth of the School of Education faculty had written major books as well as 1.8 articles in refereed journals per faculty member per year. When I came here, only one person had written a book and that was Jean Shaw. One thing that I was asked most about was about diversity. We started with one Black faculty member, Dorothy Henderson. At the end of my tenth year, 18 percent of the faculty were Black. I would like to think that I helped but it was really done predominantly by the faculty themselves touting the opportunities here. I was really proud of that.

Back row, Joe Blackbourn, Jim Payne, and Dudley Sykes

One of our Black faculty, Dr. Theopolis “T. P.” Vinson, got his master’s degree here and was attending a social at the Chancellor’s residence. I met him and was so impressed with him as an individual that I asked for his name and number and told him that when we get an opening, I’m going to give you a call. He was from Birmingham, Alabama. I took the piece of paper with his contact information on it and kept it on my desk. When we had an opening two or three years later, I called. His grandmother answered the phone. I said I’d like to speak to T. P. Vinson. She responded that he was down at the Haberdashery. I didn’t know what the Haberdashery was so I said when he gets in will you have him call me. I got off the phone and got the dictionary and looked up Haberdashery. When he called, I told him I’d met him two or three years ago at the Chancellor’s reception. We have an opening and I want you to come. I told him we were going to put him in a doctoral program and will hire you as a faculty member. He came and he was successful, becoming Assistant Dean and he was a spectacular teacher. As I mentioned, I came from very modest means and one day, he came into my office and said “Dean, I want to talk to you about the way you dress. You never button the second button above the sleeve on your shirts. Intelligent people button that button. I’d like to see you button that button.” From that point on, I have always buttoned that button. Regrettably, he passed away at a young age.

June 26, 1959 – March 15, 2003

Brown: Did you have a mentor who influenced your career choice?

Payne: I had been running Allen’s Drive-In there in Topeka. A Vocational-Rehabilitation (Voc-Rehab) person came in asking us if we would hire persons from the Kansas Neurological Institute, an institution which at that time was called mental retardation. This was during the Kennedy Administration during which time they tried to get employers to hire the mentally handicapped/mentally retarded. At that time, I was the general manager and I trained everybody. I hired the first person as a dishwasher and he was very successful, so I moved him to the fountain and hired another dishwasher, then moved him to the fountain, then to the garnish, etc. Pretty soon about half of the employees were from the Institution, none of whom were literate. Many couldn’t sign their name and it took a while to train them but once trained they did the job, showed up every day, and didn’t quit. Restaurants have a terrible turnover. However, I didn’t have any turnover. They were so good and so loyal that Corporate said: “Look, instead of you managing, we’re going to send you around to the drive-ins to increase market share profitability and to establish crews that are from institutions.” So, the next thing, they sent me to Fairway in Kansas City, Kansas. I went to Fairway, did the same thing there, brought people in from the institution, trained them, got everything done, then they put me over on State Street and I did the same thing there. Then, they moved me to Lawrence, Kansas. That changed my life. I went to Lawrence which is where the University of Kansas is. I did the same thing there. All of a sudden, I decided I wanted to know something about mental retardation. I got a catalog, looked under education trying to find a course that had the name “mental retardation” in it. I found the course “Teaching Parents How to Teach the Mentally Retarded” taught by Dr. Norris Haring. I didn’t know Dr. Haring was internationally famous in emotional disturbance. He was teaching the course and I enrolled in the course. The first thing Dr. Haring does is to have everyone in the class tell why they are taking the class. Everybody’s taking the course to get master’s degrees, and they are all practicing teachers and counselors and I’m a manager of Allen’s Drive-In at the bottom of the hill. When I told him this, he stopped and said “What? I think you’re in the wrong class, stay after class.” So, after class, I go up and I talk with him and explained to him what I was doing. He asked why I was there, and I told him I wanted to know something about mental retardation. It was in the title of the course. He asked what I wanted to know. I explained to him that over half the people I’ve hired are from the institutions and they’ve been diagnosed as mentally retarded and I’d like to know a little more about it. From that point on, after every class period, he had me stay after class. After four or five classes, I could see he was curious and invited him to come down to see what we’re doing and he responded, “I thought you’d never ask!” The next morning he showed up at 8. We didn’t serve breakfast, but we were busy setting up for lunch. I introduced him to the entire crew, whether they were from the institution or whether they weren’t. They all told him who they were and what they did. Then we sat at the booth at the back. Allen’s Drive-In was like two Sonics hooked together along with a Shoney’s. It was big. We were famous in the mid-west. It was soon approaching 11 a.m. and I told Dr. Haring that we’re going to get smothered in here in just a few minutes. We have one of the largest lunch breaks in the chain and I’m going to have to go up and help a little bit. Things started happening and cars were pouring in. The crew just went to work. Norris Haring gets up out of the booth and sits at the counter where he can see all the employees. They were a fine-oiled machine, knocking orders out. We finish the entire lunch hour, people start cleaning up, and I go back to the back booth. He starts asking me how did I train them so I explained how I trained them using pennies as reinforcement and they could exchange it for chocolate mints, then candy bars, to cigarettes (at that time you could sell cigarettes). He was amazed. He told me I was way ahead of my time. After the next class period, he pulled me aside and said they were going to get me out of the restaurant business. He said I’m going to get you a job as a Voc-Rehab Counselor. You’re going to work here for six months and come to work for me with a Federal grant called the Special Education Vocational Rehabilitation Cooperative Grant, the only one in the United States. He said Voc-Rehab and Special Ed don’t like one another. We’re going to combine the two and you’re going to be a Placement Counselor. It’s going to get national recognition. I went for six months there, then worked for him for three years as a Rehab Counselor. Then after being the Rehab Counselor they named me Director of the Wyandotte County School and Sheltered Workshop for a year and then I was moved to be the first Director of Head Start. I did that for three years, then went to the University of Virginia. From then on, I was a professor. Norris Haring didn’t ask me, he merely said we’re going to get you out of the business, you’re going to be a counselor, you’re going to work for me. He worked with me all the way through my professional career. He passed away about four months ago. I never got a chance to go back and thank him although I did call him and was able to tell him the impact he had on my life. He did this for others including Larry Tyler, Jim Kauffman, and Don Ball. We all graduated at the same time from the University of Kansas.

Brown: What skill would you like to master?

Payne: This may sound strange, but I want to be a stand-up comic. I’ve been fascinated with stand-up probably ever since high school. When I filled out the papers to retire, I told my wife I’d like to try a second career in stand-up. I wrote up a plan for stand-up and then a couple of days later, I called the owners of Rafters on the Square. I knew that on Sunday, they had brunch with a band. I told them on the phone that I wanted to try to be a stand-up comic, that I was retiring from the University and that I was 83 years old. I just like talking. They invited me to come to the Annex on Wednesday (underneath Rafters). I met with the two owners and they listened and asked about my routine. They didn’t want it to be dirty or offensive. So, I did a little audition then. After a few minutes, they invited me to do my routine during the break. I showed up on Sunday, did my routine, then the band resumed playing. My wife Esim and I reviewed the performance and talked about what needed improvement. We both felt positive (as did the sound man there). I was asked to perform at all three of their venues—Rafters on the Square, Rafters on the Water, and The Annex. I went back on Sunday to perform but COVID-19 came along, so there were no customers, no band, therefore no performance. However, we have remained in touch and I am hopeful to return and perform when the restaurants reopen. The virus has derailed my new career.

Brown: What were some of the turning points in your life?

Payne: I haven’t had many but the big turning points in my life were my decision not to be a professional baseball player, coming back from Florida to Topeka was huge. Getting married to my high school sweetheart Ruth Ann and having children was certainly a turning point. I was blessed to have a wonderful marriage for over 30 years. Her death brought me to my knees. Then meeting and marrying Esim was a turning point at which I inherited two stepsons. Probably, I’d have to say Norris Haring taking me out of the drive-in business and putting me into academia, to a more professional type of life was also a turning point.

Brown: If someone narrated your life, who would you want to be the narrator?

Payne: That would have to be George Allen, Jr., former Governor and Senator of Virginia. He took my very large lecture class when I was teaching at the University of Virginia. He’s been a dear friend and we have stayed in touch. He even endorsed one of my books. He introduced me to his father, George Allen, who was the General Manager and Coach of the Washington Redskins. Through that, I became a “coach”/advisor/consultant to Coach Allen. I believe that former Chancellor Robert Khayat left the Redskins as a kicker the year before I became an advisor to George Allen. The reason I would have George Allen, Jr. narrate my life is that he knows a lot about me, and he was my lawyer. He graduated, got a law degree, then I hired him when I got into some scrapes that he got me out of. The thing that George Allen remembers about me is I got a speeding ticket. I didn’t think I was speeding and didn’t deserve the ticket. I wanted to take it to court. I was so upset about it, I had my speedometer checked and I was certain that I had not been speeding. I was doing some consulting with an automobile dealership in Savannah, Georgia, and the owner was friends with a very famous polygrapher. I flew to Savannah and took a polygraph. The polygrapher said I don’t know if you were speeding or not, but you certainly don’t think you were speeding. We took the polygraph to the judge and pled not guilty. My attorney approached the bench and explained the issue. The opposing attorney said the polygraph could not be used. The judge stated he had never seen a polygraph, but he declared me guilty. I told George Allen we were going to appeal to a higher court. He asked if I was certain because it’s going to get expensive. I was adamant. The jury trial was going to be in a town, a couple of hours from Charlottesville. We were traveling in George’s truck. He was chewing tobacco as he was driving and had a spittoon on the dash. We’re talking and driving to this town, smaller than Oxford—why I do not know this town was chosen—and there are police cars everywhere! George said, “Gosh, they must have a murder case or something here. I’ve never seen so many police cars.” We discovered they were there for me! Apparently in Florida, they had overturned radar detectors because someone had tracked a tree going 50 miles an hour. So, they were on the alert.

The only defense we had was that I didn’t think I was speeding. The jury is there, the judge is there, and before we begin, the judge calls George in and says that he’s heard about the polygraph and warns that it is not to be mentioned. George relays the message to me. The police officers are there all decked out in their uniforms and they looked impressive. They present all kinds of evidence and devices for more than an hour, then it is my turn to testify. George asks me what transpired, and I responded that I came over the hill, I glanced down at my speedometer, I was on cruise control, and didn’t brake at all. They arrested me and said I was speeding. I said I wasn’t speeding. I had my speedometer checked and I’m not accusing anybody of wrongdoing, but something is wrong because I wasn’t speeding. That was it. The judge listened and then asked to see George Allen in his chambers. George returns and tells me that they want me to plead guilty of having faulty equipment. It won’t go on your record, there’s no violation. They merely want you to plead guilty to having faulty equipment. I told George that the equipment wasn’t defective and I’m not going to lie. He returns to the judge’s chambers asking that the jury make the determination. The judge is furious and instructs the jury, then dismisses the jury who deliberated for over an hour. George said that he thought something funny was going on since he believed that there would be at least one person who believes you. If it goes another thirty minutes, we’re going to win this case, or they’ll have a hung jury. Within five minutes, the jury comes in and they find me guilty. I’m about to leave and I see about four policemen involved in the arrest who came up to me and they said we’ve never seen anyone to hold to their principles like you. We know that you believe you weren’t speeding, but we also know that you were speeding. And I don’t want to disclose how much this appeal to this ticket cost me!

Brown: What’s the best vacation you’ve ever taken, and why was it the best?

Payne: The best vacation ever was to King’s Dominion in Richmond, Virginia. My two girls (Janet was about 8 and Kim was in high school), Ruth Ann, and I loved going to King’s Dominion to ride the flume. The flume is the ride where you go down and the water splashes on you. We would come up to the top and it would stop, then there’s a guy there who would release it before it goes down into the water, and we would all yell out “Is this the way to King’s Dominion!” We’d get back in line and do it repeatedly. We just loved it!

Brown: I know you are an avid golfer and have written a book about golf along with producing some YouTube videos. How did you get interested in golf and why does it keep your interest?

Payne: In the work that I had done as a Rehabilitation Counselor, I had developed a theory on how to persuade employers to hire the handicapped. The theory was eventually adopted by not only Kansas but also Virginia and Pennsylvania. I trained every placement counselor in the State of Pennsylvania and over half the counselors in Virginia. When I was recruited to Virginia, they wanted a person that had a background in Voc-Rehab and had a doctorate in special education. After accepting the job, I discovered I was the only applicant. I was there to teach a course called Rehabilitation Techniques. I taught the course using my theory and within a matter of just a few years, I was teaching the largest enrollment course at the University of Virginia. I was teaching two sections of 500 students back to back. Sometimes, they would give me a room that would hold 1,000. There was a waiting list to get into the class. The class was very, very popular. I taught this theory. Later the theory developed into what my own theory called PeopleWise –a wise way of dealing with self and others. I have trademarked the word. A person in the class, like George Allen, was Otis Fulton. He was a center for the University of Virginia basketball team. Two years after he graduated, he came to my house—no call, no appointment—and knocks on the door. He told me he had figured out how to take my theory and make it improve a physical skill. He said he was the center for the basketball team but a very poor free-throw shooter. I took your theory, applied it, and now I’m an excellent free-throw shooter. Next thing I know, we’re down on the playground a block away. He’s shooting free-throws, I’m rebounding. He makes 25 or more in a row and we go back to the house, and while sitting at the kitchen table, he teaches me my own theory. At that point, I’m getting ready to move to Mississippi and Coach Hunt was the basketball coach here. The second-year I was here, I went to visit Coach Hunt to tell him about this theory about free-throw shooting. He was interested. I worked up psychological profiles on all the players, I physically went on the floor, and divided them into groups based on their learning ability, showed them the technique for improving the mental approach—how to improve confidence and focus—and eventually get “into the zone” on demand. Bruce Trambarker and Rod Barnes are two that stand out in my mind. After learning how to do it, Bruce made 100 free-throws in a row. Then, 110 and 112, then he turned to Coach Hunt and he asked when he could go into the shower. The Coach told him he could go in when he missed. Bruce threw the ball against the backboard and went in to take a shower. I also taught Rod Barnes who was a player, and who later became the Ole Miss basketball coach. He made 3, 4, 5 free throws in a row and broke into a big grin. Then he made another 5 in a row and declared that he “got it” and would never be the same. From that point on, he shot over 90 percent in practice and in games. I also went to the high school to talk with Coach Sherman. I worked with that team which went on to become state champions.

Somehow, Larry Wagster who was the former golf coach at Ole Miss heard about this and got in touch with me. He said I think we can convert this into putting a golf ball. He took me under his wing, and he taught me how to putt. I had played golf before, but I hadn’t really taken it seriously. He showed me the physical part of putting which is set-up and stroke. I was dealing with the mental part. He and I wrote the book PEOPLEWISE Putting: Get Your Brain in the Game. The book did not sell well; however, it did get into the hands of some people at the Green to Tee Academy in Chicago which was well known. I got invited to feature the book at the PGA Expo in Orlando. They sponsored a booth for me. They had seen me at the book expo at Washington DC where I was presenting the book there. I never got to work with any of the professionals.

I wrote another couple of books but have since moved on to how to teach anybody how to get into the zone on demand. That’s how I got into golf. I have developed a putter with my grandson, a senior in high school, that I have patented and tested at the Ole Miss Golf Course. It is statistically superior. I tested it with 100 walk-ons. I have designed the putter around an educational model and psychological model as to how the brain works. The way I did this was in the books that I had written, I said it’s not the putter, it’s the person holding the putter. After about my third book, Larry Wagster told me that some putters are superior to others. I asked him what he meant, and he began to share with me about balance and feel. I started studying how putters were made—the engineering part—and I started studying the history of putters. None of them approached the psychological. Once you learn the principles of putting, the rest is all mental—mental toughness. It’s concentration, focus, “zoneness”, and flow. I took that information and designed this putter which is an odd-looking putter but it’s legal. We have a certificate from the USGA stating that it’s legal, thanks to my grandson’s initiative to get that certification. We own the patent, we own the trademark. It’s called the “Paynedini Magical Putter.” “Paynedini” comes from when I was in high school and on to college to earn money, I traveled as a magician, and that was my stage name. I am trying to get enough money to produce the putter.

Brown: What life skills are rarely taught but extremely useful?

Payne: In high schools and colleges, they teach a consumer science class where you learn the price of things and expand your knowledge about buying things. You might get a little money management, but I feel that the skills I have developed would be useful if every high school kid was taught about money management and understanding compound interest, saving. I didn’t know any of that. But what I’ve really gotten into is the psychology of selling. I think that everybody ought to learn about the psychology of selling. If you don’t know the psychology of selling, you might be sold something you don’t need, you can’t use, or can’t afford. For instance, when Ruth Ann and I got married, we bought a trailer, a 10 x 55 foot Van Dyke trailer and we weren’t in the trailer but a week or two, and a person knocked on our door selling encyclopedias. The next thing we know, we’re the proud owner of a set of encyclopedias that we didn’t want, didn’t need, or could afford. We sat down afterwards and wondered how could this person come into our home and sell us a set of encyclopedias that we didn’t want, need, or could afford and I have a degree in psychology. What I did was to get a part-time job selling encyclopedias. I learned the tricks of selling encyclopedias which has a lot to do with stress and emotion. Of course, you establish rapport, then you insert psychological stress. When people are under stress, they don’t think clearly. That’s why lawyers try to stress expert witnesses because they don’t want the person to think clearly. This happens in other professions but in selling it’s a systemized system. I learned a great deal about how people think in one or two months of selling encyclopedias than I did in four years getting a degree in psychology. I’ve become rather well known in the country on how to teach people how to sell, even writing a book called PeopleWise Selling: The Art of Selling Brain to Brain. It sold pretty well. I got a call recently to do a presentation for a group of real estate agents. I now think of selling as artistic where I used to think of it as unethical. People go to car dealerships and are often sold a car that maybe they might want, they might use, and maybe can afford but they didn’t buy the car—they were sold the car. I believe people should buy rather than be sold.

Brown: What makes you roll your eyes every time you see/hear it?

Payne: Government over-reach. It kills me when I hear someone say that’s an overreach of the government. For instance, today we have masks. People will say I have individual rights, it’s an overreach of the government to make me wear a mask. The same was true of seatbelts when people complained about having to wear a seatbelt. The same can be said about wearing helmets when riding motorcycles and bicycles. Sometimes, for me, the government knows what it’s doing. I think during this Coronavirus, the government understands, but we won’t do it, we won’t stay six feet apart. Instead of coming out and mandating it as they did with seatbelts and helmets, they won’t mandate masks.

Brown: What brings you great joy?

Payne: Kids, grandchildren. All I have to do is see them. Makes no difference what we’re doing. They give me great joy. Also being in special education, every time I see a kid or an adult when they master something, this could be taking their first step or being able to read their first word or recognize their first letter. The joy that they feel of this accomplishment fills my heart. The joy spills over into me. I find it so gratifying. I think that what we need to do is provide opportunities, especially for kids or adults, to succeed and excel.

Brown: It is said that we learn something every day. What is something new that you’ve learned recently?

Payne: What I’m learning is about stand-up. I’m learning about pace, flow, audience, and receptiveness. I’m learning about silence. You have to be able to know when to pause. This has been a lesson for me. I watch comedians on YouTube. My daughters have given me a thing called “master class” of magicians and comedians, I study it and I consider it to be a craft. I’m trying to master the craft. I want to give it a shot. I really don’t care if I’m successful, I just want to see what it’s like. It’s similar to when I ran for political office a few years ago. I was running for the experience. I think I could have done a good job but I’m really more interested in the experience than success. I’d like to know what it would be like to travel around, stay in hotels, and perform.

Brown: What habit do you have now that you wish you started much earlier?

Payne: I was fascinated by Larry Wagster who taught me the physical parts of putting and then about muscle memory. In reading about muscle memory, it sets in after 20,000 repetitions, according to the experts. So, if I’m going to putt a golf ball for muscle memory to come in, swing without thinking, worrying where my hands are and all that, I must achieve 20,000 repetitions. I’m into my 18,000 repetitions. I’ve moved from 50 percent to 75 percent accuracy. Supposedly when I get to 20,000, I’ll be above 80-85 percent. I do it every day. I putt every day if the weather allows.

Brown: What life lesson(s) would you like to pass along?

Payne: People who have learning disabilities or have dyslexia, that it’s not the end of the world. If I could just communicate this to the parents or to the individuals themselves, to just keep moving forward, do what’s right, and everything’s going to be fine. Along that same line, because of my dyslexia, I would like for people to understand that those individuals who struggle with reading are not dumb or stupid. It’s not because they are not motivated or because they are not interested. They just have problems. Of the individuals who have problems with reading is about 10 percent. Of that 10 percent, 90 percent of them can learn how to read with good instruction. The remaining 1 percent, which is the one I’m in. I’ve tried every trick in the book. I know how to do it, I understand it, but I still have difficulty and today at 83 years of age, I read at about the sixth-grade level. Yet, I’ve written over 30 books, 3 of which were the largest selling in the field.

Brown: What’s your biggest day-to-day challenge?

Payne: I had heart surgery about a year ago that took nearly eight hours. It was quite serious. I didn’t realize until after I recovered, that there was less than a 50-50 chance I’d survive. But I survived and got through the therapy. It was agonizing. Today I get around fine. Of course, with this corona virus, I don’t get to go too far. If you were to see me, I have no joint pain, no headaches. I’m in as good a shape as I was five years ago. But I’m not as strong and I don’t have endurance. When I go out to get the mail, it’s up a hill and when I go out and get back, I’m huffing and puffing.

Brown: What has been your routine since retirement? Do you have any hobbies?

Payne: I get up and work on the treadmill for 30 minutes, then the stationary bike for 30 minutes, then I shower. After I eat breakfast, I’ll go somewhere and putt it for a while. Then I go to lunch. After lunch, if I don’t take a nap, Esim and I do something together. She’s an exceptionally good ping pong player and we’ll play ping pong at home. Or we might just talk, have a drink. I might rehearse my stand-up routine. She listens and is a real patient. She gives me feedback. Then there’s dinner. We have been bingeing Netflix, then to bed around 11.

Brown: What remains on your bucket list?

Payne: My bucket list is just to get an agent to become a stand-up comic. I want to get an agent. I have a literary agent, but I have to find someone to represent me and help me get auditions. I’m 83 and I plan to do that.

Bonnie Brown is a retired staff member of the University of Mississippi. She most recently served as Mentoring Coordinator for the Ole Miss Women’s Council for Philanthropy. For questions or comments, email her at bbrown@olemiss.edu.