Contributors

Bonnie Brown: Q&A with Ole Miss Retiree John Robin Bradley

*Editor’s Note: The latest interview in the Ole Miss Retirees features is John Robin Bradley. The organization’s mission is to enable all of the university’s faculty and staff retirees to maintain and promote a close association with the university. It is the goal of the Ole Miss Faculty/Staff Retirees Association to maintain communication by providing opportunities to attend and participate in events and presentations.

John Robin Bradley has had quite a distinguished career and is widely respected as an attorney and faculty member. Professor Bradley brought into the classroom his humor and his vast knowledge of the legal profession. This Delta native has a wonderful story to share.

Brown: You grew up in the Mississippi Delta. Describe your home town and what was special about growing up there.

Bradley: The town of Inverness, population 1,000, had its gravel streets paved when the town was 50 years old, and I was 10. There were two town doctors and many stores. My friends and I had the run of the town on bicycles and foot, and adults, both black and white, helped keep us safe in our heedless innocence. The sense of community was something we took for granted, as everyone knew everyone else, and we spent our lives close to each other–in schools, churches and civic life.

As with other parts of the Delta, cotton was the principal crop. There were three cotton gins in town. Farm mechanization came gradually, culminating with the mechanical cotton picker being in full force by the mid-1950s. My father’s farm still had a few mules by that time, but farming and the local economy changed completely.

Brown: Tell us about your parents and any siblings.

Bradley: My parents both were born and spent practically their entire lives in Inverness, although in different ways. When my father was age 6, his father was shot from ambush and killed, leaving his mother to raise seven children. She moved from farm to town and somehow did what was needed.

My mother’s Jewish father came to this country as a child with his family, doubtless fleeing the east European anti-Semitism of the late 1800s. His family was part of the Jewish migration from New York to the South. My mother’s mother was born in this country of Jewish immigrants from Poland. Both families found success as merchants.

My sister was nearly two when I was born, and we grew up riding ponies and squabbling. She hustled through high school in three years and through college in another three. “Why?.” I asked her years later. “I was in a hurry.” No further explanation. She and my younger sister spent their adult lives in Texas. Neither is living now.

Brown: What’s your earliest memory?

Bradley: Among my indelible early memories are the rationing programs during World War II—sugar and many other food items, shoes, cars, gasoline, and tires. Bubble gum and Hershey bars came available after the war’s end.

Brown: Where did you go to school?

Bradley: My grades 1-12 were in an architect-designed building of white stucco and red-tiled roof with wood floors, large windows, no air conditioning, and no lighted sports fields. All 12 grades were in the same building. The spacious grounds were studded with mature oak trees.

My college years were at Mississippi College and summer schools in Mexico and Austria.

Brown: You were a star athlete in high school. What was your favorite sport and why?

Bradley: In the small-enrollment school, nearly everyone was on a sports team. When I was a 15-year-old eleventh grader, luck made me a star in the first football game of 1953, a fourth-quarter comeback win for our new coach.

Football, basketball, baseball, tennis, and track all were great fun, but I was never much of a basketball player. Team camaraderie was the most important stimulus.

Brown: What subjects were hardest for you in school?

Bradley: None. School came easy.

Brown: How did you respond when someone asked you what you wanted to be when you grew up?

Bradley: I never had any idea of something so remote as becoming a grown-up.

Brown: What was your very first job, perhaps as a teen or earlier. What were your responsibilities/pay?

Bradley: At age 14, I worked in the summer for the town street department at a variety of assigned jobs–digging ditches with a shovel; laying pipes; cutting grass with a sling blade on shoulders of town streets, often leading a small crew of police arrestees who were working off their fines; and operating a gasoline mower to cut grass in a town park. The job was 7 a.m. to 12 and 1 p.m. to 6, 10 hours a day for 5 days a week, and 4 hours on Saturday–54 hours a week at 40 cents an hour.

My job the next summer was at a local grain elevator which paid the federal minimum wage of 75 cents an hour plus half more for hours over 40 a week. My main task was using a device to obtain a sample of each load that a farmer hauled to the elevator and to use another device to determine the per bushel weight of that load of grain. I then prepared a report showing that information and the farm name.

Brown: Who influenced your career choice? How old were you when you decided on your career path?

Bradley: A full scholarship offer from Tulane law school led me to life after college. I knew no lawyers before that.

Brown: Please talk about your career path and your journey to Ole Miss. What was your first job?

Bradley: When I went to Tulane law school, I was in love with Laura. She was on her way to graduate school in history at the University of Mississippi. Her National Defense Education Act (NDEA) scholarship paid more than my full law school scholarship, so I transferred and graduated from the University of Mississippi law school.

Luckily, I was Editor-in-Chief of the Mississippi Law Journal during my third year in school and finished first in my class. So, getting a job was not hard. I decided on a Jackson law firm, then called Wise, Smith & Carter.

Brown: Tell us about your experience working in a private law firm after graduation from Law School.

Bradley: I was fortunate to work in a small law firm whose four partners helped me with the steep learning curve. Everything I did was new to me. It happened that I could do the work and found the challenges satisfying.

My second law job was as a “house counsel” for a group of companies in a then-growing business—a fast-paced corporate practice that brought me in regular contact with executives, accountants, engineers, salesmen. Again, I learned about a new world.

Brown: Tell us how/when your Ole Miss “story” began? Who hired you? How long did you work at Ole Miss?

Bradley: During my next-to-last semester in law school, Dean Robert J. Farley called me to his office and said, “John, the faculty and I would like for you to stay on next year and teach with us, then go to Yale to study for a year, and then return to our faculty.”

As a young-looking 24 and completely new to the world of law, I thanked him, said I would like to teach, but only after I got some experience as a lawyer. Four years later, Dean Joshua Morse extended an offer to join the faculty. This was based on my law student record and my work, along with other young lawyers, of instructing first-year law students in a short, on-campus course.

After joining the law faculty in June 1966, I retired forty-seven years later in 2013. Two of those years I was on leave-of-absence and taught elsewhere.

Brown: Where did you teach on your leaves of absence and how did you make the choice of where to teach during that period? What was your experience?

Bradley: I liked the students, faculty, school and town when I taught at Florida State University College of Law and also at the University of Richmond School of Law. Both times, I was invited by the school.

Brown: I understand that you chaired the hiring committee in the law school for quite some time and were recognized for your hospitality to potential candidates. Can you tell us about that experience?

Bradley: Law school enrollments grew in the late 1970s and 1980s, and faculty turnover was significant. The school usually had one or more positions to fill each year, and we looked to the national pool for faculty prospects. We were extraordinarily fortunate to interview on campus and to hire outstanding men and women, and it was heartening that so many remained for productive careers here. Having the opportunity to host prospective faculty members and tell them about the town, the university, and the law school also meant getting to know that person. (Later, I learned that my auto tours gave the impression that the town was twice its size and twice as interesting.) Every one of them was a person with an admirable record of accomplishment. That was an enviable experience for me to have such associations.

Brown: John Grisham was one of your students, as was his son. Can you talk about that relationship and experience?

Bradley: John was in a two-semester course with me called Contracts his first year—a class of about 120 students. A number of years later, he introduced himself to me at Square Books as a former student, this just before his first book was published and before he moved to Oxford. We then became friends. I looked in my earlier files for that class. The file showed he never missed class and wrote excellent exam answers. I never miss the opportunity to claim him as a former student. He is one of my few friends who is rich, famous and an all-around admirable human being as is his wife Renee. Many years later their son was my student in that same course. And that was another pleasure for me.

Brown: You are recognized for your expertise in worker’s compensation. Please tell us when and why you became interested in this subject.

Bradley: In my first year on the faculty I was assigned to teach a course called Employees’ Rights. By necessity, I began systematically learning about the statutory regulation of the employment relationship apart from the separate field of labor union organizing.

The bulky part of the topic dealt with the compensation of employment injuries, a subject that was newly dealt in the U. S. in the twentieth century by a combination of federal and state laws. It was an area of active law practice, student interest, and ripe for research and writing. Learning that the subject was an extensive system in itself of both procedural and substantive law, I made it into a separate course and an area of my professional work.

Brown: You were honored as the inaugural Legend Award recipient presented by the chapter of the Black Law Students Association. Talk about what that recognition meant to you.

Bradley: When I joined the law faculty in 1966, it was clear to me that the past practices in the South of racially-segregated public education were wrong-headed and left the area out of the mainstream of American life. The law school, with the help of a new Ford Foundation grant, was beginning to recruit able African-American students. The experience of racially-integrated education was new both to current and new law students.

Fortunately, because of the community where I grew up, being with African-Americans was familiar and comfortable for me, and I was glad to have a role in recruiting and befriending African-American students.

It was not surprising when I saw our law school graduates become professional and community leaders. I was privileged to be part of the change at the law school, and I feel honored to be noted as one who had a role over the years in helping students adjust and learn.

Brown: How did you and your wife Laura meet?

Bradley: We were friends and classmates in college; her parents, both college professors, were my teachers and friends. Our courting days began shortly after college.

Brown: Can you share with us more about Laura and your family/grands?

Bradley: Laura has read more books than anyone I know; was president of the area Girl Scouts Council after being active locally with the Scouts; went on the Trans-Siberian train among her seven trips to Russia; enjoyed her tennis doubles games for many years, often with wives of Ole Miss football coaches; and nourished the lives of our two children. Our son Mark is not living now; his widow Susan and son Sam continue to live in Virginia Beach. Our daughter Claire graduated from Duke, worked in book publishing in New York for over 30 years before moving with her husband and two children to Franklin, Tennessee in 2018. Claire and her family are pictured below. Grandsons Sam and Daniel Robin are college students, and granddaughter Angela is a high schooler.

Brown: You and your wife Laura recently gave additional financial support to the Medgar Evans Scholarship Endowment. Please tell us more about this endowment.

Bradley: In 2008, and asking for no publicity, we made a sizeable gift to establish this endowment. Its purpose was to help fill a need for the law school to continue to attract able students to promote a diverse student population. A few years ago, I pledged another sizeable gift to match dollar-for-dollar a stated goal for the law school to raise from others. That was completed earlier in 2020 thanks to a number of generous donors.

includes (seated, from left) law school Dean Susan Duncan, Laura Bradley, Kye Handy and Jeffrey Graves

and (standing, from left) Warren Cox, John R. Bradley, Corrie Cockrell, Courtney Cockrell and Keveon Taylor

Photo by Joe Ellis/UMMC Public Affairs

Brown: You have won many awards throughout your career. What accomplishment are you most proud of?

Bradley: Being able to think independently.

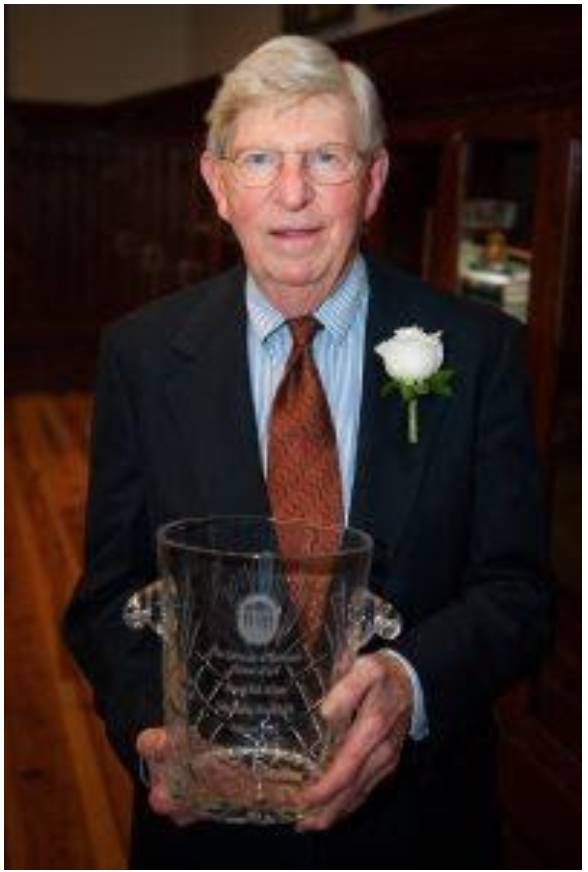

Law Alumni Hall of Fame

Brown: What one question can you ask someone to find out the most about them?

Bradley: “Where did you go to high school?”

Brown: What are the most useful skills you have?

Bradley: To assimilate and organize information in a useful form.

Brown: What are your pet peeves?

Bradley: Unthinking bigots

Brown: What is your creative outlet?

Bradley: Professional writing. My professional writing included a number of articles on a variety of legal topics, most on workers’ compensation law, both for law journals and other publications for lawyers and judges. Also, I co-authored two workers’ compensation books for commercial publication. One is a comprehensive treatise published in 2006 called “Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Law.” A new edition is published each year with revisions and updated material.

Brown: If there was something in your past you were able to go back and do differently, what would that be?

Bradley: Since I could not do anything to grow tall, I would try, despite my tin ear, to learn something about music.

Brown: What is the best part of your day?

Bradley: Being tired enough to go to bed.

Brown: What is the best advice you ever received?

Bradley: “If it is worth doing, it is worth doing right.”

Brown: Talk about something that always cheers you up when you think about it?

Bradley: My hiking trips in the mountains of several countries. Some of the hiking trips in Montana, Wyoming, British Columbia, England, France and Spain, both my wife and I joined other groups or struck out on marked trails. Some in Alaska and Montana I was with a group from the Sierra Club or Nature Conservancy, but my wife chose not to take part.

Brown: To what do you attribute the biggest successes in your life?

Bradley: Luck.

Brown: Tell us something about yourself that not many people may know.

Bradley: In my tennis days, my underspin, backhand down the line was my best shot.

Brown: What are you passionate about?

Bradley: The natural world that we inherited.

Brown: What “old person” things do you do or say?

Bradley: “picture show”

Brown: Do you have hobbies?

Bradley: I am an amateur naturalist, emphasis on amateur. The outdoors was where we small-town youngsters in the 1940s and 1950s spent our lives prowling the bayous, lakes, woods and fields. Frog gigging was only one of our exploits. This was our pre-television world. Much later I began to learn more about the fauna and flora, both locally and in the mountain areas I visited. It was luck that I had good books and good teachers to learn details about birds, trees, and the geologic forces that gave the world around us its shape.

Brown: What has become your routine since retirement?

Bradley: Spending time with family and friends and reading far beyond my professional work.

Brown: To quote Katherine Meadowcroft, Cultural activist and writer, “What one leaves behind is the quality of one’s life, the summation of the choices and actions one makes in this life, our spiritual and moral values.” What is your legacy?

Bradley: I hope: Do justice, love mercy, walk humbly.

Bonnie Brown is a retired staff member of the University of Mississippi. She most recently served as Mentoring Coordinator for the Ole Miss Women’s Council for Philanthropy. For questions or comments, email her at bbrown@olemiss.edu.