Contributors

Bonnie Brown: Q&A with Ole Miss Retiree Dr. Andy Mullins

*Editor’s Note: The latest interview in the Ole Miss Retirees features is Andy Mullins. The organization’s mission is to enable all of the university’s faculty and staff retirees to maintain and promote a close association with the university. It is the goal of the Ole Miss Faculty/Staff Retirees Association to maintain communication by providing opportunities to attend and participate in events and presentations.

Everyone knows Andy Mullins. He’s a friendly, kind gentleman. He has a great sense of humor. He doesn’t take himself seriously, but he is very serious and passionate about education, Ole Miss sports, and his family.

Brown: I know you grew up in Macon, Mississippi. What is special about the place you grew up?

Mullins: It was a farming community in the lower part of the Black Prairie or Rolling Prairie of east Mississippi. Beautiful farm country which had rich black soil on a limestone base and went from just south of Macon up to just south of Tupelo. Cotton was king when I was growing up in Noxubee, Lowndes, Oktibbeha, Chickasaw, Monroe, and part of Lee counties. A small town in which you knew most everybody. My house where I grew up was built by my grandfather in 1920 when he moved into town and sold his farming place in northeast Noxubee Co. He bought a hardware store on main street which was called Mullins Hardware that my father worked in and ran for 50 years. It was an idyllic place to grow up in the 1950s and half of the 1960s. My house was right on highway 45 which ran through Macon and went from Mobile, Ala. to Chicago, Ill. A boy could get on his bike in the summer and be gone from home all day, exploring in Cedar Creek looking for sharks’ teeth which were plentiful in the limestone banks, going to the American Legion swimming pool, going to the Little League baseball field, making up fun games with friends, etc Just had to be home for supper at 6 p.m.

Brown: What are some of the differences between present-day Macon and the Macon of your childhood?

Mullins: Noxubee Co. and Macon the county seat have shrunk in population from about 18,000 in the county to 11,000. Macon has many fewer people also. Mechanization in farming replaced jobs for the unskilled and many African Americans left for jobs in the north, and many young people who went away to college never came back due to more opportunities elsewhere. Like so many of the small towns in rural America, Macon is “drying up.”

Brown: Please talk about your parents, siblings and any crazy aunts and uncles.

Mullins: My father was Andrew Poindexter Mullins, Sr. better known by his nickname of ‘Ike’ which he got while a student at Ole Miss. Everybody knew him as Ike and not Andrew. He never remembered where that nickname came from. Andrew came from my grandmother’s friendship with the president of Mississippi Industrial College for Women at Columbus. Andrew Kincannon, who later became Chancellor of the University of Mississippi (UM), was a good friend of my grandparents. So my grandmother named my father Andrew after her friend. My Dad’s father built the house on the main street, bought the hardware store and another farm, then died at age 39 of a ruptured appendix. My grandmother who was the most incredible person I have ever known raised three boys ran the hardware store and the farm and taught a Sunday school class at the First Methodist Church in Macon for 42 years. She was the first female elected in Noxubee County to the county school board, was the first female head of the Chamber of Commerce, and was an early women’s libber. She never remarried and died at age 83. She lived there with us in the big house. She set an example of hard work, education, and Christian discipleship for the entire family. My father graduated from Ole Miss in 1929 at age 20. My mother was from West Point and was a graduate of Mississippi State College for Women (MSCW) as it was called when she was there. My sister was seven years older than me and graduated from the University of North Carolina. Education was stressed to us by my parents and grandmother. There was never a question of what you would do after graduating high school. I had a great uncle, my grandmother’s brother, whose name was O. Q. Poindexter and a real eccentric.

Brown: What’s the most important lesson you learned from your parents?

Mullins: I worked in Mullins Hardware from the time I was six years old through and after college before I moved to Jackson. It was the old-fashioned hardware in a farming community. I learned so many lessons about people working there. My father taught me to always trust a person’s word as sacrosanct until there was a reason not to. A handshake was trusted enough in most cases. My mother was the kind who would push you to achieve but in a kind and gentle way. However, you could always tell when she was disappointed in your effort. She was a force in my decision to go to Millsaps College rather than Ole Miss although it was clear my father was disappointed. I am so sorry that my father died the year I started working at Ole Miss. He would have been proud beyond words if he could have visited me in my office in the Lyceum.

Brown: When you were a kid and someone asked you what you wanted to be when you grew up, what was your response?

Mullins: I idolized a first cousin of mine who was 10 years older. When he was at Millsaps, he majored in geology so I wanted to be a geologist even though I had no idea what that meant—it just sounded impressive, then when he went to UM Law School, I wanted to go to law school. When I was real little, I told people I wanted to be a fireman. Don’t ask me why. I guess I liked the shiny firetruck.

Brown: Where did you go to school?

Mullins: Macon elementary, then Noxubee County High School, then Millsaps College for a BA in History. While teaching high school history and coaching football and tennis at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School in Jackson, I finished a master of education in history at Mississippi College in Clinton, then spent 1979-80 as a graduate assistant for Jean Jones in the Counseling Center at Ole Miss and began my doctorate in higher education.

Brown: Talk about your high school experience. Did you play sports, join clubs?

Mullins: Noxubee County High School was a big rural school in Macon on the site of where a great-great-grandfather of mine, W. R. Poindexter, was the founder and proprietor of the Calhoun Institute which was a finishing school for young ladies. The Institute started back after the war ended and closed in the 1880s. Noxubee County High School had a lot of poor white kids in the period of 1962 to when I graduated in 1966. I graduated from a segregated school and did not have a class with a black student until my first year at Millsaps College. I was an all Choctaw Conference athlete in football and in baseball at Noxubee County. I was in the regular clubs—Beta Club, Letterman’s Club, Student Council, etc. It was not the best educational experience in preparing a student to go to a challenging liberal arts college like Millsaps College. I really had to hustle academically during my freshman year at Millsaps. However, there was a great BIG incentive to pass—you were drafted and sent to Vietnam if you flunked out.

Brown: Did you have a curfew?

Mullins: Not really but when I came in regardless of the time I had to tell my mother goodnight with a kiss on her cheek which she could use to tell if you had been drinking beer which I did not do in high school. If you came in much later than midnight, you were asked many questions at breakfast by my mother. I remember once she was really drilling me because I had been around 2 a.m. getting in. My father said, “If you want him to lie, then just keep asking questions.” He had once been a teenage boy.

Brown: What was your first job and what were your responsibilities?

Mullins: At age 7 or 8 I would run errands from the hardware store, take the bank deposits across the street to the bank, carry things out to the cars for the women, and help unload trucks when they delivered merchandise in the back of the store.

Brown: What advice would you give to your 20-year-old self?

Mullins: Don’t worry so much about what people think of you and stop worrying so much about the future and just enjoy being 20 years old.

Brown: Did you have a mentor who influenced your career choice?

Mullins: Not really because I have always loved history and I knew that was what I wanted to major in at Millsaps from the freshman year. My history professor did help me make a decision to teach history when I was offered the job at St. Andrew’s. I had taken no education classes and was doubting whether I should teach rather than enter law school, and he said why don’t you try it for a year and if you don’t like it you can always go to law school. From the minute I walked into my first class at St. Andrew’s, I was hooked on education.

Brown: Tell us how/when your Ole Miss “story” began? Who hired you? How long did you work at Ole Miss?

Mullins: I met Robert Khayat when he came down to the Governor’s Mansion for dinner when I was working with Governor Winter who was going out of office in January of 1984. Robert Khayat wanted Governor Winter to apply for the chancellorship of the University of Mississippi. Governor Winter turned down the IHL Board’s offer to be the chancellor (I had planned to come to Ole Miss with him and was surprised when he turned it down), and I went to work as a Special Assistant to the State Superintendent of Education, Dick Boyd, and the newly-appointed State Board of Education chaired by Jack Reed of Tupelo. I became dear friends with both Dick Boyd and Jack Reed. I had staffed Governor Winter’s Blue Ribbon Committee on School Finance in 1980 and Jack was the Chairman of that Committee. Under Governor Winter I was his Special Assistant for Education and worked on every aspect of the 1982 Education Reform Act (ERA). Therefore, Jack Reed told Dick Boyd who did not know me to hire me as a Special Assistant to help implement all 17 programs in the Education Reform Act. I handled every education bill for the State Board of Education for three superintendents of education over a 10-year period.

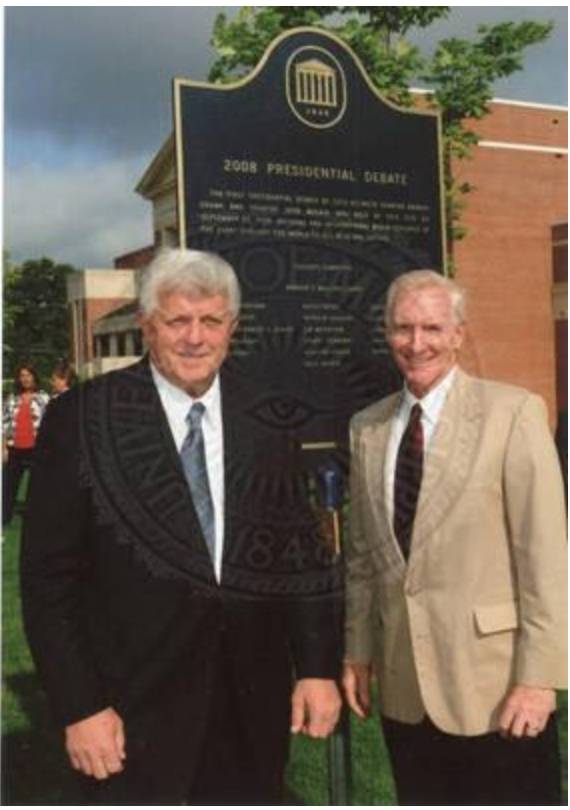

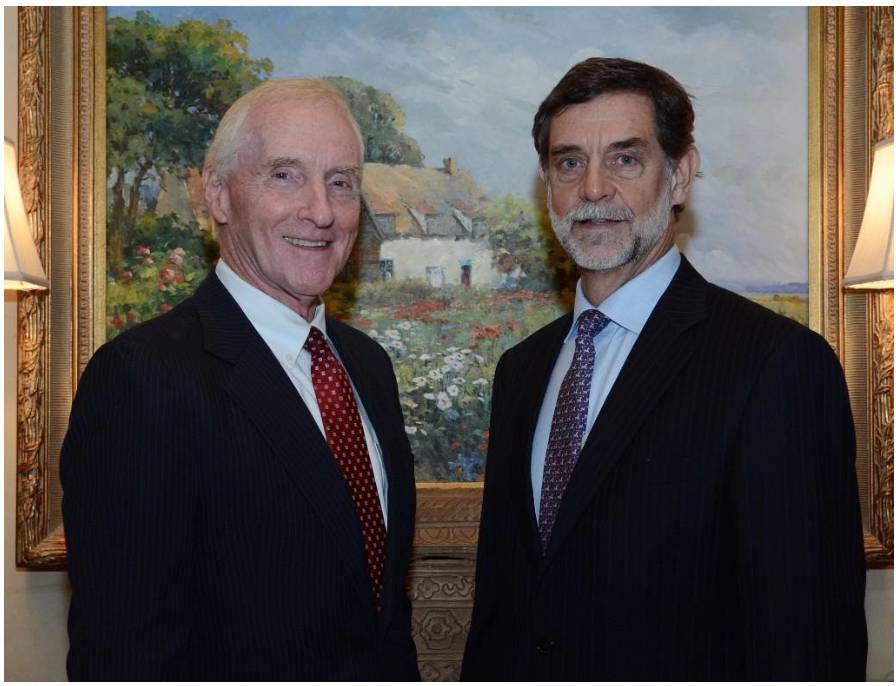

Gerald Turner had been appointed Chancellor in 1984 after Winter refused to accept it. I got to know Gerald when I would see him and Les Wyatt when they came to lobby the legislature. Also, I had been involved in creating the Mississippi Teacher Corps (MTC) in 1989, and it was placed at Ole Miss in the School of Education. Gerald started recruiting me to come to Ole Miss as his assistant when Les wanted to move into another position. My wife, Lisa, had been teaching inner-city Jackson in some of the toughest schools in the public system for 13 years, and she needed a change. Therefore, after about three years of being recruited by Gerald, we decided to move to Oxford. I went to work with Chancellor Turner and in the School of Education teaching in the Mississippi Teacher Corps. That move was in August of 1994. Gerald moved to SMU in 1995, and Robert Khayat hired me as his Special Assistant in 1995. I did many things for Chancellor Khayat over the 14 years of his tenure as chancellor—governmental relations with the city, county, and state with some federal work, served as the liaison to the public schools, the community colleges, worked with the IHL Board and the other university governmental representatives, served as the chairman of the Presidential Debate Committee which included being the contact person for the Presidential Debate Commission during the Debate in 2008, served as chairman of the Football Game Day Preparations Committee for 18 seasons, and taught in and co-directed the Mississippi Teacher Corps. Then when Chancellor Khayat retired, I served as Chief of Staff to Chancellor Dan Jones for four years with most of the same duties and responsibilities. I then retired from the administration in 2013 but continued to teach and administer in the Mississippi Teacher Corps until July of 2019. Then I retired from all duties at least the ones I got paid to do. Therefore, I worked at UM for 25 years.

Brown: What did you know about Ole Miss before you accepted a position here?

Mullins: I had several good friends whom I had gotten to know when I was a graduate student and worked in the Counseling Center in 1979-80. I received my doctorate at Ole Miss in 1992 and several of my professors were still there. I had worked with the Mississippi Teacher Corps since 1989 when it had been placed at UM. I did not teach in it until 1994 but I placed every one of the teachers in it in school districts since the beginning of the Corps. The first class was in 1990 so I had to make several trips from the State Department of Education to the School of Education to speak to the classes and talk to them about their placements. I knew quite a bit about UM.

Brown: You wore many hats during your years at Ole Miss. What was the most rewarding/most challenging of your responsibilities?

Mullins: Governmental relations are very challenging at any level. It was a challenge at Ole Miss, but it was not as difficult as it had been at the State Department of Education because I did not have to handle as much legislation as I did working for all of K-12 education.

The most rewarding and challenging responsibility was working with the Presidential Debate Committee (PDC) during the three-year process of preparing for the 2008 Debate. It was right down my alley and included all the things I like—governmental relations, history, politics, education, leadership, and the inner workings of big organizations. It was hard work. But I got so much satisfaction working with the UM professors, staff, and administrators all who pulled together to make it happen. The Presidential Debate Commission staff included the most professional people with whom I have ever worked. I continued to consult with other universities on behalf of the PDC over the next two debates.

Managing game day was fun at times but hard work with many complaints to handle which I really got tired of doing.

Brown: I know that you chaired the Football Game Day Preparations Committee. Please share with us a favorite story about a football game day that stands out in your memory.

Mullins: One time I was sitting on the steps of the Lyceum waiting on someone to meet me to pick up their tickets when two young female students pulled their car right up on the sidewalk directly across the street from the front of the Lyceum. They parked it there completely blocking the sidewalk. I said, “excuse me ladies but you cannot park there.” I never had any kind of official shirt on to signify I was an official of the university. They both gave me a “go to hell” look and one said, “Mind your own damn business!” as they walked away. I said OK, I will do just that as they left, I assumed to meet someone. So, I minded my own “damn business” as instructed by calling the wrecker which had the car towed in 10 minutes. I waited until after it was towed really hoping they would come back, but they did not. Their “advice” to me cost them $100.

There are many more stories but too many to tell.

Brown: You and a Harvard journalism student, Amy Gutman, established the Mississippi Teacher Corp (MTC), an alternate-route teaching program. Tell us about this program and its impact on our state and why it was important to you personally.

Mullins: The Mississippi Teacher Corps was made possible by the creation of an alternative route for teacher certification or licensure. In Mississippi, there had been no alternate route for those who wanted to be licensed teachers but wanted a way to get licensed other than the traditional major in education.

In 1970 when I graduated from Millsaps with a major in history, there was no alternate route. I got a job teaching at St. Andrew’s Episcopal High School although I had no courses in education while an undergraduate. St. Andrew’s required its teachers to be licensed by the state of Mississippi. The only way I could start teaching immediately was to apply for a teacher permit from the State Department of Education. This permit required the license applicant to take six hours of pedagogy a year while teaching. This requirement was the minimum to get the permit renewed. A total of thirty-six hours was mandated along with the successful passage of the National Teacher Exam in order to get a license issued by the State. I took the full six years to complete the thirty-six hours. For several of these courses, I questioned the value added to my ability to teach history.

Therefore, when I started working as a Special Assistant for Governor William Winter in 1980, the opportunity came to make changes in the entire education system of public education. As one of the 17 programs in the Education Reform Act of 1982, the redesign of the Certification Commission gave those of us working on the Act just what was needed. Because of my personal experience in getting certified, I was determined to get those changes written into the new law governing teacher licensure.

Because of the new law, the State Board of Education approved procedures necessary for an alternative license for grades 7-12 teachers in the late 1980s. This alternate route was not viewed as needed by many of the deans of schools of education in the universities and private colleges in the state. In fact, it received outright hostile disapproval with many of them openly opposing it. The only dean who supported it as a way to get more teachers in many of the school districts having problems finding teachers was the UM Dean of Education, Jim Payne. He felt schools of education needed to create ways to remain relevant to the education changes that were occurring in many states due to comprehensive reform such as Mississippi had passed. The Institutions of Higher Learning Commissioner, Ray Cleere, was also a supporter of the alternate route and was a good friend of Dean Payne’s.

In the late 1980s, I was a Special Assistant to the first appointed State Superintendent of Education, Richard Boyd. There were many local superintendents in the Mississippi Delta who began asking me for assistance in locating teachers especially in mathematics and the sciences. At that time the State Department of Education did not have a Teacher Center to aid in placing needed teachers. Therefore, my secretary and I created an ad hoc center in my office to locate possible teachers for those districts in high need. The teacher shortage had begun and was rapidly increasing. I personally knew a large number of these local superintendents and had been in their districts many times while working on the ERA of 1982.

Meanwhile, the state legislature had recently passed a concurrent resolution calling on the State Board of Education which governed K-12 and the Institutions of Higher Learning—the College Board—which governed the eight universities to cooperate on some issue or project. There had been little contact between the two education boards. I was looking for something that would be a jump-start project to meet this mandate.

In 1988, Harvard journalism major, Amy Gutman, was interning at a newspaper in the Delta. She was in my office in the State Superintendent’s suite interviewing me about the imminent teacher shortage in the Delta. We were interrupted several times by my phone ringing due to calls from desperate district superintendents looking for teachers. Gutman said now that you have the alternate route, the recruiting of “idealistic” liberal arts majors from the Ivy League universities—much like the Peace Corps had done in the 1960s—should be tried. Her idea immediately struck me as a potential project to meet the legislative mandate for the two boards to work together on a project. The State Board of Education licensed teachers by the alternate route which required twelve hours of education courses which were taken at the universities governed by the College Board. I felt she had a great idea.

From there she visited with IHL Commissioner Cleere who endorsed her idea, and we discussed how it should be implemented. Richard Boyd endorsed it as well. Cleere got a grant from the Phil Hardin Foundation to support it for the first three years. It was initially housed administratively at the IHL Board Office. Because Dean Payne was the only dean in support of an alternative route, the training program was located at UM. Because I had been involved with the law establishing the alternate route and knew the local superintendents, I was asked to place the new Mississippi Teacher Corps applicants in the districts. Amy Gutman worked with the Commissioner’s Office for one year in the initial design of the program which included recruiting from the various universities. Then she returned to Harvard.

The initial training at UM was directed by an education professor, Dr. Peggy Emerson. It was a one-year program with no graduate program attached. This first-class entered UM and began their teaching assignments as licensed alternate route teachers in 1990.

The next two classes, 1991, and 1992 remained one-year programs. In the spring of 1992, Commissioner Cleere, informed me that the start-up grant which was funding the MTC was ending, and there were no more resources to support it. He also said he had heard complaints that were negative about the training program. The critics claimed it was not adequately preparing the teachers for the classroom. These teachers knew their subject matter but needed skills on how to deliver it to their students. Many of these students came to these schools badly damaged by generational poverty and lacked basic reading skills. Cleere made it clear that the program would not survive without a funding source and a change in the training procedures. Two things then happened which were essential to the continuation of the fledgling MTC.

Since I was working directly with the state legislature for the State Board of Education and the State Superintendent, I began to advocate with the education committee chairs and the appropriation committee chairs the establishment of a line-item appropriation in the IHL budget specifically to support MTC. This attempt was successful. The initial appropriation was for $200,000 as an identified expenditure which would have to be renewed each year in the IHL budget. It specifically stated that the line item appropriation was for the Mississippi Teacher Corps. Therefore each year, if it was renewed, the IHL Board would send the money to UM specifically for the MTC which was housed in the School of Education.

The second occurrence which was equally essential to the continuation of the program was the decision to make the MTC a two-year program with a “free” master’s degree awarded to those teachers who completed two years of teaching and the necessary coursework. The Associate Dean of Education, Jim Chambless, was in charge of restructuring the program to make it more successful in the basic teaching skills which were lacking in the original one-year training program. At this point, the MTC’s overall governance moved completely from the IHL Office where Amy Gutman and Whitney Thompson had guided it to the School of Education at UM. Jim Chambless became the Director.

In 1994, I left the State Superintendent of Education’s office to become a Special Assistant to UM Chancellor Gerald Turner. I was asked to continue to place the MTC teachers as I had from the State Department of Education and to teach two classes in the master’s program. Therefore since 1989, I have been associated with the MTC as a co-founder, co-director, assistant director, and associate professor while being a Special Assistant to three State Superintendents of Education and Special Assistant/Chief of Staff to three University of Mississippi Chancellors.

There have been 30 classes that have included the 750 applicants who have been accepted into the program. I have placed all 750 in the school districts where they were assigned to teach. Of the 750 who started the program, 618 have completed the program. This number does not include the 25 who entered the program as the 30th class. They have a year to go. These 750 teachers have come to the University of Mississippi for their training and coursework from 246 colleges and universities in the US and Canada.

Being able to help the high poverty school districts find well-trained teachers has brought me much satisfaction and so has to see this program continue into its 31st year. Governor Winter gave me the greatest gift you can give someone—the opportunity to make a difference in the lives of others. I have satisfaction knowing that I have given this same opportunity to hundreds of teachers through the Mississippi Teacher Corps.

Brown: Talk about the Principal Corps, a full-time graduate program, where classroom teachers learn the skills to become K-12 leaders and principals.

Mullins: The Mississippi Principal Corps came directly out of the Mississippi Teacher Corps as far as the idea for it. There are three chronic complaints from MTC teachers over the last 30 years. The one that gave me the idea for the Principal Corps was the complaint that the principals these teachers found in the schools they were assigned to were stressed out, poorly trained as building-level administrators, and overworked. So as this complaint was repeated year to year, there was a well-known educator, Art Levine, Dean of Teachers College at Columbia University, who wrote a scathing report on the way principals were being trained at the schools of education all across the US. At the time I had been appointed to the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) by Governor Ronnie Musgrove. At an SREB meeting in Atlanta, I heard Dr. Levine address a room full of deans of education from the various colleges and universities across the sixteen member states that belonged to the SREB. It was one of the most intense meetings I have attended in my many years in education. Levine told them his comprehensive study showed that school principals were being trained to run the K-12 schools of the 1970s, and they needed to change the training program from top to bottom. He said principals should be trained as the instructional leaders of the schools and not just the “keys carriers.” They should be trained in how to evaluate good teaching, inculcate technology into the curriculum, build consensus, and be the leaders of instruction at every level. They should be transformational leaders and no longer just trained to run the busses on time, organize the school day, be head of the discipline, and open and close the buildings thus the “keys carriers.” Principals could hire assistants to do these duties. The most important task of these transformational new principals was to be the instructional leaders and concentrate on coordinating instruction within the assessment system.

Then he told them that a doctorate was not needed for building level principals. A good master’s program that emphasized these new skills was needed to run today’s schools, and the current masters and doctorate programs, the way they were taught, were obsolete and no longer effective for principals. When he finished, there were small pockets of applause but mostly the deans were stunned. I came home with a copy of his report and went directly to Dean Tom Burnham with whom I had worked when he was State Superintendent of Education. I had contacted him to recruit him to apply for the deanship when it came open. He had retired from Mississippi at the time and was a local superintendent in North Carolina. He agreed to come home and apply for the Dean of Education at UM. Tom was chosen Dean in 2004. He liked what Art Levine said immensely. I then went to Chancellor Robert Khayat with my idea based on the way the Mississippi Teacher Corps was designed. Chancellor Khayat liked the idea and said for me to take it to the legislature. He must have seen the disappointment on my face when I said that would not work, and we would get some watered-down version of what I had in mind. Then he said, “Well let’s go see our old friend, Jim Barksdale.” Chancellor Khayat, Dean Burnham, and I went to Barksdale’s home in Jackson to talk to him about it. I knew Jim had been very disappointed in the caliber of the principals he had found in the Barksdale Reading Program schools. So I called his brother Claiborne to get his ideas on this project and to find out the best way to approach Jim for funding my idea. The meeting with Jim lasted about an hour, and I presented my idea with the backing of Dean Burnham. He agreed to fund it for the first five years, then it was up to the university to find the funding to continue.

Barksdale also paid for Art Levine to come to UM to advise us on a good model, and there were other experts as well who came primarily to meet with Dean Burnham who was leading the design team to put the final structure in place before we selected the first class. We were off and running. We hired Dr. Susan McClelland, a principal in New Albany and an adjunct professor in the School of Education, as the first Director. The experienced teachers who wanted to train as building-level principals were the applicants. They would be trained in districts that supported them or alternatively, some were not tied to any particular district but assigned to follow and work beside a good principal for two semesters. They would come back to campus one week a month for classes, thereby combining theory with practical practices of on the job experience.

When Tom Burnham completed a second five-year term as the State Superintendent of Education, he was hired as the Director of the Mississippi Principal Corps when Dr. McClelland moved into various positions within the School of Education, but she continued teaching in the MPC.

This Program is built on developing transformational leaders for Mississippi’s public schools and these well-trained administrators are sought after as school leaders. Jim Barksdale was so proud of the MPC after the first five years that he recommitted for 20 more years to help with the funding. Other funding comes from school districts which are sponsoring a participant, and from some funding from the State Department of Education. The 2020 class will be the 12th class, and the MPC has graduated 133 thus far with a master’s in school administration. Dr. Tom Burnham is starting his 9th year as the Director.

Brown: As I understand it, this program requires that candidates receive the endorsement of their superintendent. Has this program been widely accepted by the superintendents?

Mullins: The applicants do not have to have the endorsement of their superintendents. However, because the trainees get the salaries they made their last year of teaching, it definitely helps to have assistance paying their salaries and benefits during this one year of training. There are a few salaries and benefits paid by the assistance from the Mississippi Department of Education depending on its appropriation from the state legislature each year. Jim Barksdale’s contribution also plays a big part but mostly they receive their salaries from a combination of sources. The number each year who are admitted into the program is largely determined by the amount of money available for that fiscal year. Like the Mississippi Teacher Corps, the Mississippi Principal Corps is a program that has done well and grown in reputation and status.

Brown: You were named Millsaps’ Alumnus of the Year in 2014. What did that recognition mean to you?

Mullins: This honor really meant a lot to me. I love Millsaps College. My four developmental years there literally changed my life, and I got to tell my story of how that happened when I was asked to be the keynote speaker to the Founders Day Luncheon in 2015. I was asked because I was the 2014 Alumnus of the Year. I have been active in many things at Millsaps and the current president, Rob Pearigen, is a good friend. He asked me to serve as his unpaid advisor primarily on his administration design and as a head hunter for some of his administrative positions. He had come to Millsaps as a professor of political science and Dean of Students at the University of the South or Sewanee. He had not been in a position as president nor had he worked directly under a president, so he asked for my assistance with an administrative line-up. He appointed me as chair of the Millsaps Board of Visitors which is a board of alumni from various years. We look at every aspect of the College once a year in detail and then make recommendations to the President and the Governing Board of Directors. I have chaired this Board for seven years, and many of our recommendations have been implemented in landscaping, in athletics, in fundraising, in academics, in student life, in the physical plant, and in new construction. It has been my pleasure to try to make a difference for my alma mater.

Brown: How did you and your wife Lisa meet? Tell us about your children and family.

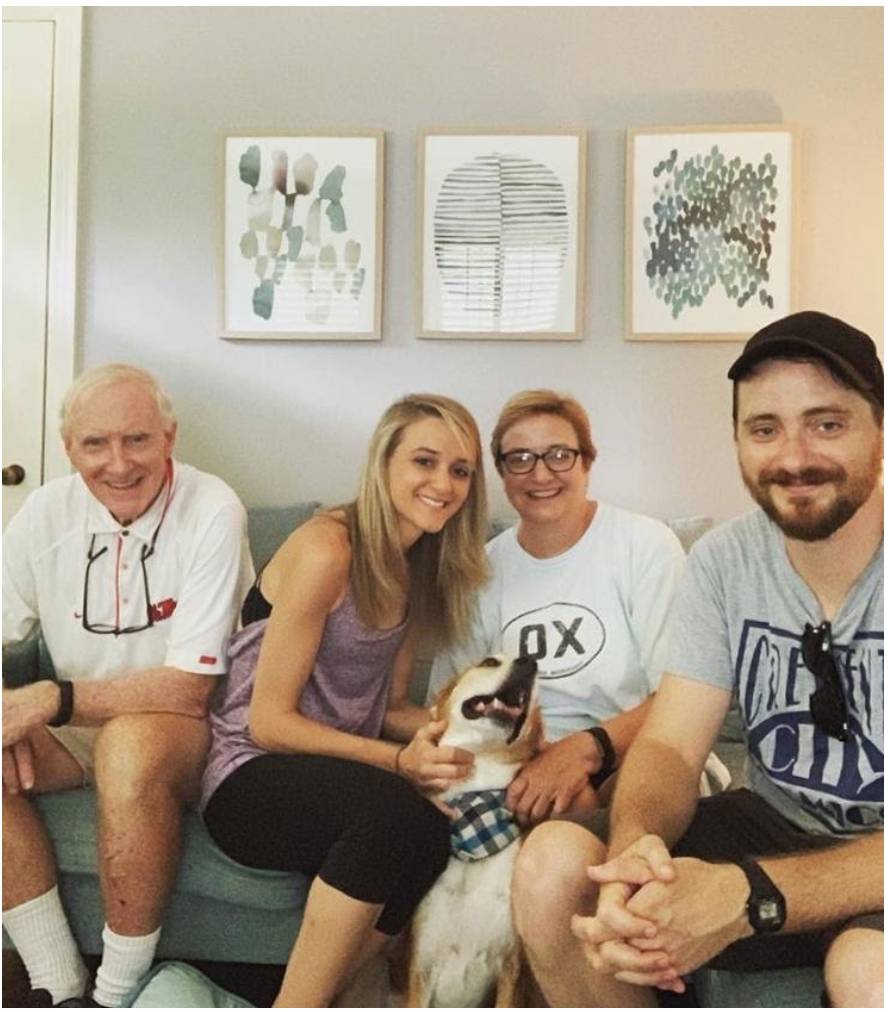

Mullins: My wife of 35 years and I met in the fall of 1982 in a restaurant/bar right across the street from Millsaps College called “CS’s”. It has been a Millsaps hangout for students for 60 years of more. I was working for Governor Winter and a former high school student of mine, and a Millsaps friend of Lisa’s told me there was a friend of hers she wanted me to meet. I was 34 and had never been married but too busy working on the Education Reform Act of 1982 to be looking very hard. Lisa was a public school teacher in Jackson and was 24, 10 years younger than I. We met in CS’s and hit it off. We still eat at that table when we go there for lunch if the table is available. One of the co-owners knows what table it was because she was a waitress there 35 years ago. We dated for two years and a half and got married in August of 1985. She was the middle child of five children of Clay and Dot Lee. Clay was the pastor of Galloway Methodist Church in Jackson at the time and that is where we got married by him and my Methodist preacher brother-in-law. Clay became Bishop of the Holston Conference which covers east Tennessee and southwestern Virginia in 1988 and served for eight years. Clay and Dot moved to Knoxville during this time. Lisa continued teaching and when Winter went out of office, I went to work in the State Superintendent of Education’s Office. We had our first child, Andrew III, in January of 1987 and Katie in 1990. In 1994, we moved to Oxford. Lisa took Lib Sansing’s (David’s wife) first-grade teaching position when she retired. Lisa taught at Bramlett Elementary for 17 years. She retired after thirty years of teaching in Jackson and Oxford and still substitutes sometimes. Andrew graduated from Oxford High School and entered Ole Miss in 2005. I will admit that Lisa, class of 1980, and I, class of 1970, at Millsaps College tried to talk both of our children to go to Millsaps. Neither would have any part of it.

Andrew began working at Square Books while in high school, and he wanted to continue while at Ole Miss. He graduated in Southern Studies and in English. He got a wonderful education at Ole Miss and a great experience working at Square Books. One of his best friends today is Richard and Lisa Howorth’s son, Beckett, who currently works there. After he graduated from Ole Miss, Andrew remained in Oxford for a year working in the Athletic Department tutoring students on how to write effectively. The next year he got a graduate fellowship to the University of Massachusetts at Boston, and over the next two years, he got a master’s in American Studies while teaching some adults who were first-year college students. The summer between the two years there, he worked as an intern at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. This experience sparked an interest in archives and special collections.

After earning his master’s, he went to New Orleans because he had been dating a young lady, also a Millsaps graduate, who was teaching there. They married in 2015. She is a teacher in the New Orleans public schools, and he got a job at Tulane University in the Southern Historical Collection as a library technician. He completed his library science degree at LSU online and currently is a librarian/archivist for the New Orleans Collection in the main public library in downtown New Orleans. He also writes pieces for various blogs and publications on a variety of topics.

Katie graduated from Oxford High School a year early and enrolled at Birmingham Southern College but transferred to Ole Miss during the semester. She graduated from Ole Miss in Elementary Education and taught preschool in Madison County at Flora Elementary for two years then moved to Nashville and taught for five more in kindergarten. She moved back to Oxford in 2019 with an assistantship in Early Childhood at the UM School of Education. She finished her master’s this spring and has accepted a teaching position as a kindergarten teacher at Bramlett School where she had gone to school and where her mother had taught.

Brown: What three words best describe you?

Mullins: I asked my wife and daughter because I don’t know. They agreed on kindhearted, strong-willed, and competitive.

Brown: If you could go back and change one decision in your life, what would it be?

Mullins: I have been incredibly lucky starting with my parents. We don’t get to choose our parents and those who are gifted with good ones are fortunate and privileged. Therefore, I don’t strongly regret any decision I have ever made. I have been so very fortunate to have had the bosses I have had and don’t regret choosing to work with any of them. I have agonized over many decisions and written the plusses and minuses down for each choice, but once made I would not change a single one.

Brown: What makes you angry?

Mullins: Bullies. I cannot stand bullies who pick on vulnerable people and on animals. Nothing makes me madder than to see a child abused in public. I have almost been assaulted several times after telling somebody to stop hitting a child or abusing an animal. Cruelty to animals really gets my anger up quickly. Hearing people brag about what they have achieved and looking down their noses at those who are struggling due to having a stressful childhood also makes me angry. I have been so fortunate in so many ways not because of what I have done but just pure chance or luck. And that applies to so many people. Those who don’t recognize that fact of luck but take credit in a boastful and ungracious manner for their good fortune, really make me angry. I have to hold my tongue and be nice, but I am angry.

Brown: What makes you happy?

Mullins: Seeing acts of kindness. Helping the underdog. Helping teachers who are in the greatest profession there is. Seeing the light come on in the eyes of a student when they understand something. Getting notes from former students who thank me for changing their lives. Being around grateful and giving people.

Brown: What accomplishment are you most proud of to date?

Mullins: Not any one thing. Just being in a position to help others, especially fellow educators. Being a good father and husband and friend—at least I think I am.

Brown: How do you “re-charge?”

Mullins: I have a lot of interests—hiking up mountains—I have climbed on hiking trails to the summits of most of the high points in the USA—Mt. Whitney, Mt. Rainier, Mt. Hood, Mt. Washington (where I had hyperthermia), Mt. Mitchell, Mt. Katahdin, Cloud’s Rest, and Half Dome in Yosemite and to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and back out, and the highest mountain in the British Isles—Ben Nevis. Andrew and I climbed Ben Nevis together as well as Clingmans’s Dome and Frozen Head Mt. in Tennessee. So, I recharge by hiking on mountain trails all over the USA.

I love to visit historic sites like battlefields. I enjoy reading about the Civil War and the American Revolution battles and then walking the sites of the battles to study the strategies and decisions that affected the outcome. I love reading history and recharge from books that fellow members of the Dick Boyd Book Club read and discuss. We have read fiction and nonfiction books in the last several years that the men’s club has met, and at last count, we are near 80 books.

I love to study Mississippi history and visit places I have not been in the state.

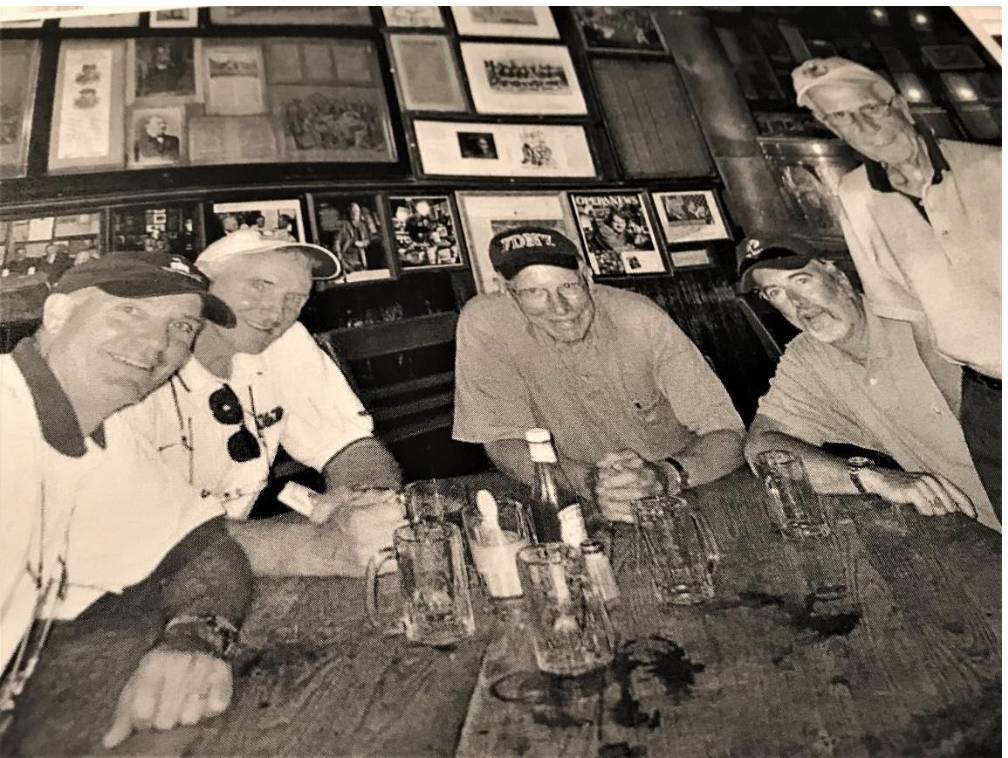

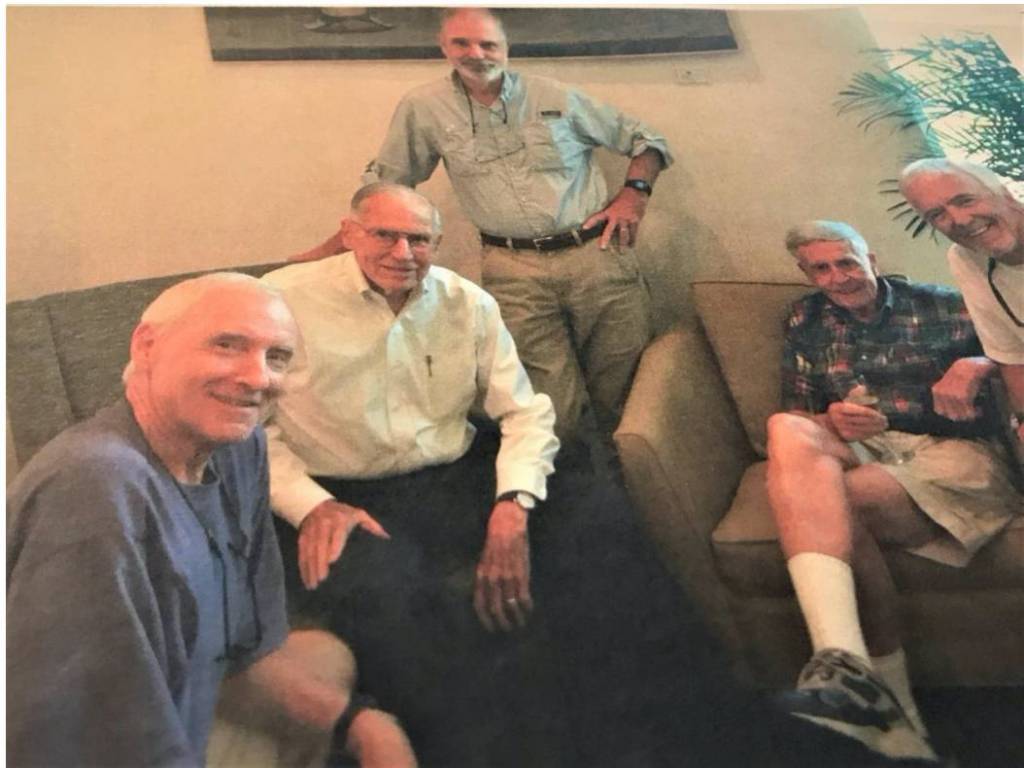

I am a sports fan. I love Ole Miss football, baseball, basketball and tennis. I go to all home football, baseball and basketball games. Lisa only goes to the basketball games which she enjoys. Governor Winter and I along with three others have gone to every (30) major league baseball park in the USA over the last 33 years. The Governor and I are the only ones of the five who have been to them all. We see three games, visit historic sites in the area, meet with interesting people and dine in mainly famous restaurants which are not fancy like historic taverns or famous sports watering holes.

I generally take the group on tours of battlefields in the area such as Gettysburg, Antietam, Bunker Hill, Lexington Green, and Concord Mass. We have had personal meetings with the following: Walter Mondale in his law office in downtown Minneapolis, Mayor Jerry Brown before he was governor of California but the mayor of Oakland at the time, Mike Dukakis, who fixed breakfast for us at his modest home in Boston, toured the territory in south-central Los Angeles, led by three gang negotiators where the riots occurred—one of the most fascinating events of my life. I have been the chronicler of these trips and have enjoyed it immensely. We started over but Governor Winter was only able to make two of the three start-overs so we haven’t gone to any the last two years. We have finished our run, but what a run it has been. Great experience with great friends!

Brown: Do you have a favorite quote? What is it and why is it your favorite?

Mullins: I have kept a book of quotes from books I have read since 1966. And who said or wrote them. So, it is ironic that one of my favorites is by someone that I can’t identify. I don’t know who said it, but here it is:

“A nation should be judged by the laughter and the smiles of its children. Not by the GNP nor military might but by the happiness of its children.”

Brown: If your life were a book, what would the title be?

Mullins: “A Lucky Man and How He Tried to Help Others Be Lucky Too”

Brown: What’s your favorite way to waste time?

Mullins: I generally don’t waste time because I have so many interests. I collect old pocket knives that are made in the USA which are like the ones we sold at Mullins Hardware. I guess I waste time looking at these and keeping them well oiled and sharpened. I have a very big book collection, and I like to work with these. Many of them are first editions and signed. A lot of them are about Mississippi, plus there are many popular historians’ books. I can’t just sit down and watch an entire series on Netflix or Prime, but I can watch these and documentaries only about two hours once a day.

I guess my friends would tell you I waste time by playing golf because I have been playing for about 20 years and have not gotten much better. I played fairly good tennis for 40 years at a competitive level for my age group. I also coached tennis at St. Andrew’s for eight years. But various injuries caused me to quit playing about five years ago, and now I only play golf and walk.

Brown: If a genie granted you three wishes right now, what would you wish for?

Mullins: I wish for a cure for chronic clinical depression which my daughter Katie has suffered from since she was a teenager. So many people suffer from this disease, and it can be debilitating at times. She is one of the bravest people I know because she will just get up and count her steps and go teach even when she just feels like sleeping all day or is very anxious and does not know why. Doctors predict as science knows more and more about the brain that many mental illnesses like depression will be healed. Modern medicine has come a long way in mitigating the symptoms, but no cure is available today.

2nd wish—I would wish for Ole Miss to win the SEC in football before I die.

3rd wish—that more progress would be made in eradicating child abuse and neglect in America.

Brown: Where’s your favorite vacation destination and why is it your favorite?

Mullins: I don’t really have a favorite but anywhere in the mountains with family and friends. Lisa prefers the beach but with my skin I can’t just sit or lie out in the sun. I would love to spend more time in Scotland which is my favorite foreign country to visit. My mother’s family came from Scotland, and I have done a roots expedition to Perth, Scotland. I love to go back for a month. I love the scenery, the people, and its history.

Brown: What’s your favorite family tradition?

Mullins: Gather around the Christmas tree with family and let the youngest child, Katie, bring each person one present at a time to be opened before anyone else opens theirs which allows the entire family to see what each person got without jumping ahead and opening theirs.

Brown: What has been your routine since retirement? Do you have any hobbies?

Mullins: Get up at the same time as when I was working. Ride a stationary bike while reading for 30 minutes, let the dog out, call my three pet crows and feed them—crows are so smart, I like to watch their behavior, let the dog in, then eat a small breakfast, check emails and messages, then take an hour or more walk in the neighborhood, around the University or around the Square including whistling through the graveyard and back to my truck usually parked at the OPC Howell Center. I try to walk 25-32 miles a week. I was a competitive runner in my age group for 30 years but again various injuries shut down the running game so I just walk at an 18 minute a mile clip. The COVID-19 has altered all our daily routines such as going to the various Bible study classes at St. Peter’s during the week, coffee club meetings every Tuesday morning at upstairs Square Books and going to Men’s Book Club meeting once a month. Also, I was speaking to various classes in MTC and MPC when needed at the School of Education.

I have too many hobbies so I really don’t ever get bored.

Brown: What’s a project you plan to do “when you have the time?”

Mullins: I have the time now to build a woodpile and have about completed that from trees that fell in the neighborhood during the spring storms. I also go down to the cemetery in Macon to the family plots and make sure they are kept clean and kill the fire ants and their mounds around the tombstones. I need to make my twice-annual trips to take care of this. While there I play golf with my best friend of 66 years who still lives in Macon. We play on the same golf course that my father was a charter member of and played there twice a week for 40 plus years.

Brown: Is there a story of yours that you don’t get to tell often enough that causes your family to roll their eyes? You can tell us.

Mullins: I asked my family but could not get an agreement, but one they have heard over and over when we are with friends and family is this one:

When Ike, my father, was in his 80’s he started having some dementia problems. He and my mother had left Macon and moved into the Orchard Retirement Center in Ridgeland to be close to us when we lived in Jackson. One day several of the family members were sitting around, and I started to ask Ike some questions. If you did not talk to him and engage him in whatever the activity was, he would tend to withdraw. Therefore, I would try to talk to him and ask questions about the old times even though he repeated things often. He had gone to Ole Miss and loved Ole Miss very much. Living in Macon he was in the vast minority of Ole Miss supporters because Macon is thirty miles from Mississippi State. Most citizens of Macon are State supporters. He and a couple of others really were teased and caught much ribbing when State beat Ole Miss in anything. Therefore, he had a deep dislike for State. So while family members were just sitting around listening to the TV or idle conversation, I asked Ike this question:

“Daddy where did you go to college? He said, “I just don’t remember, maybe if I think on it a while it might come to me, but I just can’t say.” So I asked another question. “Was it LSU?” He pondered a moment then shaking his head he said, “That does not sound right but not sure, don’t think so.” I followed with, “Was it MSCW?” (where Mom went, and his mother had gone). Again he paused, tilted his head and looked around and said, “Don’t think so, that does not sound right, but I don’t think that is it either.” I then said, “Was it Mississippi State?” Everybody was listening at this point, and I expected the same answer as the other two. But he poked out his chest and sat up proudly and stated with a resounding “HELL NO!” The entire room exploded in laughter and he looked around and joined in the laughter.

Brown: What are some things that you have marked off your bucket list?

Mullins: Bucket list— I have gone to Italy—Florence and small cities in Tuscany, Rome, Siena, Perugia, Orvieto

Other places I had on my bucket list that I have visited: Pro Football Hall of Fame, President Garfield’s home and farm National park in Medina, Ohio, Charleston, S.C.—Fort Sumter, The Citadel, Emanuel A.M.E. Church in Charleston.

Battlefields—Stones River National Battlefield in Tennessee; Bennett House in Durham North Carolina; Brices Cross Roads in Baldwyn, Mississippi; San Jacinto Battlefield in Texas; Milledgeville, Georgia; Raymond Battlefield in Mississippi; Home of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain in Brunswick, Maine; Jesse James Northfield Minnesota site of the Raid; Five Forks National Battlefield in Petersburg, Virginia; Gaines Mills Battlefield in Virginia; Grant’s Headquarters at City Point, Virginia; Cold Harbor Battlefield in Virginia; and Bunker Hill Battlefield in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

Hikes in Yosemite, the bottom of the Grand Canyon and back out by the Bright Angel Trail, Jerome Arizona, Campobello Island-Roosevelt Home, Abbey of Gethsemani near Bardstown Kentucky, and Subiaco Abbey in Subiaco, Arkansas, and Ephesus, Turkey.

What is left on the bucket list? A mile-long list of places such as New Zealand, Argentina, Chile, British Columbia, Ireland, Cooperstown New York, Normandy Beaches and Cemetery, hike on the Santiago de Compostelo in Spain, Walk across England on historic trails, Israel, Aldo Leopold’s farm in Wisconsin, Quebec, and Durango, Colorado. There are dozens of other places in the USA, overseas and right here in Mississippi that I would like to visit. I have been in 46 states and would like to make it 50.

My bucket list has been drastically reduced in the last 10 years. A lot of places were checked off when we went there on the baseball trips.

Brown: What do you want your legacy to be?

Mullins: My legacy—just an educator who tried to improve education in my home state. I am satisfied that I have given the wonderful gift of providing an opportunity to improve the lives of others to many in my career. That is the gift that Governor Winter gave to me. I am thankful I have had the opportunity to spread that gift that keeps on giving.

If I died tomorrow, I would have no regrets whatsoever. I would like to live a little longer just to see how things come out, but I have lived a very fortunate life, and I am truly thankful for it.

As that great philosopher, Winnie the Pooh, said, “How lucky I am to have something that makes saying goodbye so hard.” That sums up my career and in a way my entire life.

Bonnie Brown is a retired staff member of the University of Mississippi. She most recently served as Mentoring Coordinator for the Ole Miss Women’s Council for Philanthropy. For questions or comments, email her at bbrown@olemiss.edu.