By Jerry Mitchell

Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting

The pandemic started far from our nation, but the disease soon struck our shores.

Our leaders downplayed the possible harm, and before long, Americans began to be infected at an alarming rate.

This pandemic struck us long ago, long before COVID-19 came to the fore, infecting our hearts with a disease known as hate.

The roots of racism can be found in this hate, a toxic mix of fear and prejudice.

And when we down this deadly drink, we begin to dehumanize, giving ourselves permission to treat others as less than human, or even to destroy them.

It is what we saw in the police officers in Minneapolis, one of whom kept his knee on the neck of George Floyd until he was motionless. He refused to listen to Floyd’s pleas that he couldn’t breathe or the crowd’s cries to get off him.

It is what we saw in Georgia when white men who suspected Ahmaud Arbery of burglary, chased him down and shot him three times with a shotgun, the killer saying he had shot a “f—ing n—-.”

It is what we saw in Mississippi in 1964 when Klansmen, assisted by law enforcement, killed three young men involved in the civil rights movement and buried their bodies in an earthen dam. After gunning down James Chaney, an African-American activist from nearby Meridian, a Klansman declared, “You didn’t leave me anything but a n—–, but at least I shot me a n—–.”

So how long has this pandemic of hate been going on in the U.S.? Since we arrived on these shores hundreds of years ago, referring to the more than 5 million Native Americans who already lived here as “savages.” By the 1900s, not even 238,000 were left.

Similarly, up to 2 million Africans died on slave ships headed for the New World before becoming victims of violence in their new land. Between Reconstruction and World War II, there were more than 4,400 racial terror lynchings in the United States during the period, according to the Equal Justice Initiative.

These days, a young black man in America has a better chance of getting killed by police than he does of dying of diabetes.

The book I wrote, Race Against Time, tells the story of KKK murders that went unpunished during the Civil Rights Movement until prosecutions took place decades later. That work by families, authorities, journalists and others was indeed a pursuit of justice, but it was also a pursuit of truth because without truth, there is no justice.

Through their reign of terror from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement, the Klan sought to send a warped message throughout the nation — about who holds power, about who must live in fear, about who gets to set the final record.

Their world was one where a man like KKK leader Sam Bowers, whose Mississippi Klansmen carried out at least 10 killings, could be remembered as a small-town pinball operator rather than a terrorist. Their world was one where African Americans could be called “enemies” in their own nation, the country their ancestors had helped build, shape and improve for centuries.

The work of reinvestigating the KKK’s crimes in Mississippi has long been the work of correcting the record, of reclaiming memory about these Klansmen and their sympathizers in the halls of power.

In the cases where I’ve succeeded and those where I’ve failed, my aim has been to ensure that the truth was what wound up on the record. Only then could justice be done. Only then could the Klan’s false narrative be righted. Only then could hate be exposed for what it is.

And this is what we must do today in this new race against time, to decide if we will let hate threaten our survival, or we will finally fight this pandemic.

“Are we going to destroy this world with hate before this generation comes up?” Myrlie Evers, the 87-year-old widow of slain NAACP leader Medgar Evers, asked me. “I do ask for healing for all of us, including those whose souls are ill with hatred and bitterness. At times like this, when I feel I cannot pray, my prayer becomes one word, ‘Help.’ That is all I can do.”

On Saturday, there were signs of change in the unlikeliest of places — Mississippi, where Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton by a whopping 17% margin in 2016.

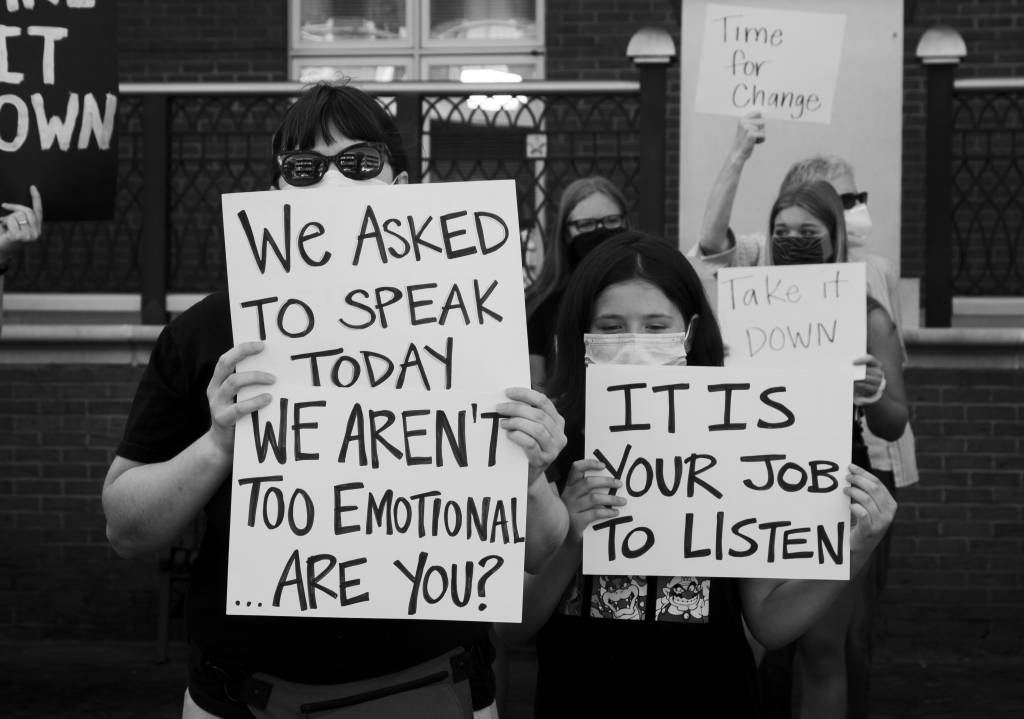

In eight different cities across the state — six of which Trump won handily — thousands poured out into the streets to protest the May 25 death of George Floyd.

One of them took place in the town of Petal, where the white mayor discounted the reason for Floyd’s death, saying, “If you can talk, you can breathe.” Despite his apology, he has received continued calls to step down, including from his own aldermen.

Lorraine Bates, a 70-year-old African-American woman, spends more than four hours a day protesting outside the mayor’s office, playing the speeches of Martin Luther King Jr. on a boombox.

The city of Starkville, where only 25,000 live, saw more than 2,000 march in the streets, carrying signs that said “Black Lives Matter,” “White Silence Is Compliance” and “Make Racism Bad Again.”

The vast majority were white.

Jackson saw more than 3,000 gather outside the governor’s mansion in their march against police brutality, perhaps the biggest protest in the capital city since the Civil Rights Movement.

“When Mississippi changes, America changes,” organizer Calvert White told those gathered. “When America changes, the world changes.”

Jerry Mitchell is an investigative reporter for the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that is exposing wrongdoing, educating and empowering Mississippians, and raising up the next generation of investigative reporters. Sign up for MCIR’s newsletters here.

Jerry Mitchell is an investigative reporter for the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization that is exposing wrongdoing, educating and empowering Mississippians, and raising up the next generation of investigative reporters. Sign up for MCIR’s newsletters here.