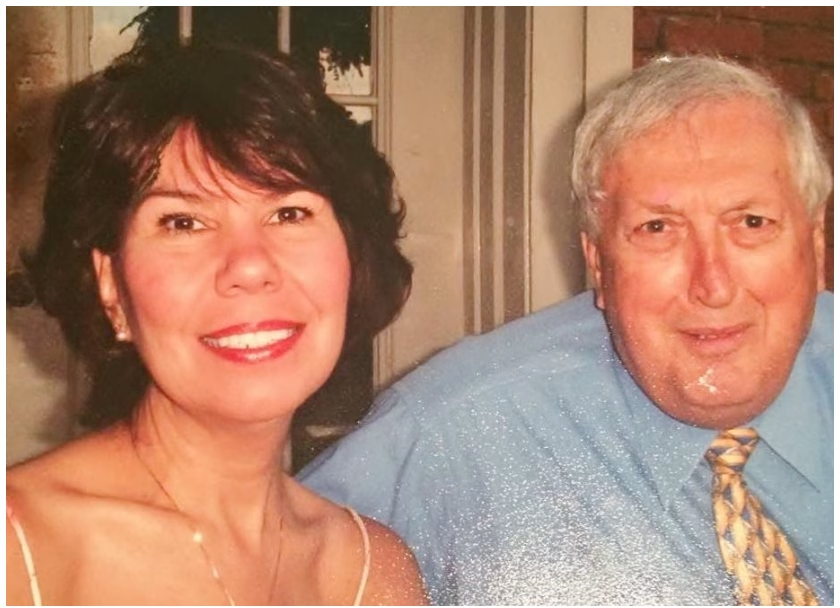

*Editor’s Note: The latest interview in the Ole Miss Retirees features is Deborah Freeland. The organization’s mission is to enable all of the university’s faculty and staff retirees to maintain and promote a close association with the university. It is the goal of the Ole Miss Faculty/Staff Retirees Association to maintain communication by providing opportunities to attend and participate in events and presentations.

Deborah Freeland is a multi-talented artist. Her detailed drawings are amazing, her photography extraordinary, and her documentary about Faulkner and Rowan Oak is in the running for a regional Emmy. Our community is fortunate that this Texas transplant brought her talents and her lovely self to Oxford.

Brown: Where did you grow up? Tell us what was special about your hometown.

Freeland: When I was a child my family lived in Houston, Texas. In the 1950’s -1960’s Houston wasn’t the huge metropolis it is now. It was more of an overgrown town. The cultural environment was artistic, progressive, and optimistic.

The first American astronauts lived in Houston and were often seen on the streets. Every schoolchild knew their names. They were more famous than any movie star. People would gather just to watch John Glenn mow his lawn.

The cuisine of Texas was different than in Mississippi. I think of Tex-Mex food and beef barbecue as home cooking.

Brown: Please talk about your childhood.

Freeland: I was a baby boomer and grew up during the post-WWII American high. We knew our neighbors then and they knew us. I could name the families from one house to the next all the way to the end of the street.

Our busy neighborhood had a comfortable and familiar rhythm. Just like clockwork, the daily newspaper was thrown in the yard by 6 a.m. On weekday mornings men left for work at 6:30 a.m. Glass bottles of milk with cardboard stoppers appeared on the doorstep by 7 a.m. The U.S. mail was delivered twice a day, 8 a.m. and 4 p.m.

The boomers were the largest generation to date and you could see it everywhere. My neighborhood was full of young children. We went through school and played together with my entire childhood. Additions to our numbers grew as the neighborhood expanded. I remember “cry rooms” in theaters, “free to use” baby strollers and “supervised playrooms” in large department stores. These parent-friendly amenities gradually disappeared as the boomers aged.

I was among the very first group of children to get the Salk Polio vaccine. People were terrified of polio. During the hot month’s many public venues, movie theaters, swimming pools, etc. would close. Parents were afraid to send their children to school. My mother knew a doctor who was able to get the vaccine early. One afternoon he called and said, “I got it!” My mother dropped everything and ran with me to his office. The fear was real. The current COVID-19 pandemic reminds me of the polio scare of the early ’50s.

The boomers were the first generation to grow up with TV. I watched as much of it as my parents would allow. My friends and I knew the TV program schedule and could sing all the theme songs. Our first TV was black and white and there were only three channels to choose from. I am still a fan of black and white vintage films including monsters and outer space movies. Years later I discovered that a lot of the movies I saw were actually filmed in color.

The summers of my childhood smelled of gardenias and freshly mowed grass. Summer didn’t just seem longer then, it was longer. The school year began after Labor Day and ended in May. I had a great deal of freedom just to play. My neighborhood friends and I played outside, mostly unsupervised. We stopped only long enough for lunch or to catch a favorite TV show. Then we hurried back outside again and stayed outside until the evening lights came on. Children playing, unsupervised, outdoors is unheard of now.

Most all of the women in my neighborhood worked in the home and minded the children, my mother included. Household chores began early and ended late.

The amount of “wash” alone was memorable. The neighborhood Maytags agitated and spun family laundry daily. It was then hung on lines strung between poles in the backyard. Every afternoon, assorted underwear, starched shirts, cloth diapers, children’s rompers, towels, bright white bed sheets and other linens dried in the sun—for all to see. You could guess the size of any family on the block by the clothes on the line. Twenty-four diapers a day floated in the breeze on the clothesline next door.

Not everyone had an air-conditioner and for a long time, my grandparents clung to an attic fan. They were not afraid to leave their windows open day or night. Bits of conversations, the clearing of dishes and the sound of a neighbors’ radio or TV could be heard from the sidewalk. I have noticed that neighborhoods today are silent.

There was a thriving Downtown Theater District in Houston. My parents took me to children’s matinee performances at the world-famous “Alley Theater” when it was located in an alley and not world-famous. I was truly amazed to see Mary Martin fly across the stage as “Peter Pan.”

Like Southerners, Texans valued their history and culture. Every year enthusiasts would ride the old “Salt Grass Trail.” The event consisted of a mile-long string of wagons and cowboys on horseback who traveled 103 miles from Cat Spring, Texas to Houston. As a child, I watched the “end of the ride” and many Christmas parades from the 3rd floor of the “Ten-Ten” (Tenneco) building downtown where my dad worked. There were also rodeos with celebrity cowboy guests. I met Roy Rodgers and sang “Happy Trails to you.” I still have a scar where I fell off a saw horse playing “Annie Oakley, Queen of the West.”

I was in grade school, January 1959, when Alaska became the 49th state. On Monday morning the whole school stood and said the Pledge of Allegiance as a 49-star flag was hoisted up the flag pole. Later we colored mimeographed maps of the USA that included Alaska. In music class, we energetically sang patriotic songs. I thought “Deep in the Heart of Texas” was a patriotic song. When school ended for the day all of the children were given little 49-star flags on sticks. We ran out the door singing and waving our little flags. I still have mine. An original 49-star flag is fairly rare because 8 months later there were 50 states.

Brown: Tell us about your parents and siblings.

Freeland: Both my parents were children of the depression and WWII. As adults, they embraced the mid-century modern world of the 1950s and 60s. My Dad was a Texan by birth. After graduating from Rice University he was immediately drafted for Korea. His math skills placed him in a ballistic meteorology unit and kept him out of combat. By profession, he was an actuary but he was also a craftsman and a fine musician. He played trumpet in the style of Al Hirt. I grew up listening to him practice. My Dad always had a project going. He built a stereo system with large speakers on both sides and a turntable that floated out of a cabinet. His father, my grandfather, had been a guitarist and singer in a Texas Swing band during the 1920s-30s. That is how he met my grandmother.

My mother was a homemaker with a sweet singing voice. She was born on a farm the youngest of 8 children. Her mother owned a prosperous little store. Growing up I heard interesting stories about the farm, the store, and her siblings.

I have one younger brother, Brett Thiel, who followed me around for years. In school, he was a math wiz and now he is a financial advisor. At one time he played the drums in a band. That is how he met my sister-in-law.

Everyone in my family was interested in the arts. Paintings, sculptures, guitars, a trumpet, a piano, a drum set, and an organ could be found in our house. My dad actually built the organ my brother and I took lessons on. His attitude was, build it and they will play.

Brown: What is your favorite family memory?

Freeland: My brother and I listening to my dad’s practice. His music and recordings filled the house all of my childhood. I can still hear each clear note.

Brown: Where did you go to school?

Freeland:

Kindergarten- lower grades in Houston, Texas

10, 11, and 12th grades, High School at Richwoods High School in Peoria, Illinois

Undergraduate school, Northern Illinois University (NIU)

Graduate School, The University of Mississippi

Brown: What subject did you enjoy most in school?

Freeland: During all of my school years I loved art, music, literature, and history classes. In grade school, I would rather decorate the bulletin boards than go out on the playground. I was honored with the “Most Talented” award in my high school graduating class.

Brown: What was your major in college?

Freeland: I was an art major, studying illustration, photography, design, and art history. The B.F.A. program at Northern Illinois University (NIU) was rigorous and intense. In addition to the general requirements for graduation, I spent double the hours in-studio classes.

We had a female or male model every day of class. My final exam was to produce in class a figure drawing from a live model. Then we taped a layer of onion skin paper over the completed figure drawing to draw and label the major bones. The second layer of onion skin was taped over that to draw and label the major muscles.

I completed my Master’s Degree in Art at Ole Miss. It was nice to be on a small friendly campus. I graduated a semester behind Bill Beckwith and Glennray Tutor. We all knew each other than and are still friends.

Brown: I read that you attended ballet school. Please talk about that.

Freeland: I was a serious student of ballet starting at age six and continued as a young adult. I was in the feeder group for the Houston Ballet. In class, we learned the choreography accompanied by a pianist and not pre-recorded music. Our pianist could pick up the pace or slow it down depending on what the instructor needed. An orchestra played during stage rehearsals and performances.

A true ballet production isn’t just about dance. It is the merging of choreography, costume design, makeup, lights, sets and music. There is a great deal of excitement backstage and worry about ribbons or elastic that might break. My costumes were muslin lined to prevent sweating through to the taffeta or silk. The bodice had “stays” that were sewn in front and back so that it “stayed” sleek and smooth. Tiny hook and eye closures were used to attach the many yards of netting that made up the skirt. At one time I thought about being a costume designer. The best way to know what costume works on stage is to have worn one.

Toe shoes are prettier on the outside than they are on the inside. The points are hard and we used sheepskin pads over our toes. Reinforced arches hold the shape. Ribbons are crossed and wrap the ankle for extra support.

It was fun. It was beautiful. But it was also a lot of hard work and very competitive. There were many other hopeful ballerinas waiting in the wings to pirouette on stage. I had boys in my classes. They were strong and agile. Some were gymnasts but others were aspiring actors. A performer who could dance, sing, and an act was a “triple threat” when it came to getting jobs.

Brown: When you were a child, how did you respond when someone asked you what you wanted to be when you grew up?

Freeland: This question made me smile. Like many little girls, I said I wanted to be a ballerina. For a time I was a ballerina. There is a coming of age moment when you pull up on your first toe shoes. I clearly remember being fitted with my point shoes.

I danced in several professional ballet performances including, Swan Lake,Fire Bird, Pandora, and Prince Igor (better known as Kismet). I have multiple broken toes to prove it.

Brown: Who influenced you in your early life?

Freeland: Definitely my artistic parents. My parents gave me a lot of art supplies and my own Kodak Brownie camera. At age seven, I was taking little black and white photographs. They were printed by Kodak on shiny paper with scalloped edges. I have had a camera ever since.

Brown: What world events, if any, impact your life growing up?

Freeland: In the late 1960s, when I was in high school, my family moved to Illinois. I kept up with many friends in Texas through visits to my grandparents. As children, we thought the world was inherently a good place. It was early in the Vietnam War when the reality of what was happening hit home.

In 1967 two men in pristine uniforms arrived at Mc Neal’s house next door.

“The Navy Department exceedingly regrets to advise you that… your son…” “Torpedo-man Second Class USN… missing in action in the (Gulf of Tonkin) since 29 July… He may be a prisoner of war… Sincere sympathy…”

My mother paid a respectful, heartfelt visit to Mrs. Mc Neal. “We are so sorry about Skipper, so very sorry. Is there anything we can do?”

Less than eight months later the same men would knock on the door of my childhood friend Christina and her 4-month-old baby.

“While performing his duty in the service of his country, February 2, 1968. (The Tet Offensive) Your husband is reported as killed in action … Sincere sympathy…”

This was only a preview of what was to come. By the time I was in college, everyone knew someone who was killed or missing in “Nam.”

During my undergraduate years, there was a lot of activism on the NIU campus. Boys I knew had an “X” or their lottery number printed on the back of their T-shirts. Nickel-plated bracelets engraved with names of POWs or MIAs were worn by girls.

Following the shootings, at Kent State, the unrest at NIU intensified. On May 5, 1970, a student protest that began on campus migrated to the town. Buildings and vehicles were damaged, the State police were called and students were arrested. The next night another rally estimated at over 5,000 (some estimated 8,000) took place and the police presence increased. More unrest happened on May 18th when an antiwar march protesting ROTC on campus rallied on the bridge to town. The next night when students headed to the bridge again the hawks turned on the doves.

The window of my dorm room faced the main street on campus and I had a clear view of what was happening. The situation quickly turned violent. I watched as the police dressed in riot gear formed a “V” and moved down the street. They began striking protesters with nightsticks and forcing them into buses. There were a lot of screaming and confusion in the dark. In an effort to stop the police, the crowd blocked the street by turning over four state vehicles and setting them on fire. One of these blazing vehicles lay upside down in front of my dormitory. My boyfriend at the time led me out the back way through the boys’ dorm and into a waiting car. When violence broke out again on May 20th, the University closed.

Years later during a trip to D.C., I would trace over-familiar names etched on the Vietnam Memorial Wall. I had known these boys. We had danced at parties and kissed in the shadows. Their average age was 21.

Ron Borne told me that he visited the memorial on a day when there was a lot of condensation on the wall. As water dripped down a little girl standing near him said, “Look mom the wall is crying too.” I found a kindred spirit in the multi-talented Ron Borne. He was a scientist who loved art and literature. He is missed by me and many others.

Brown: Did you have a mentor who influenced your career choice?

Freeland: I really didn’t have a mentor as a student at Ole Miss but Jere Allen helped me improve my portraits and figure drawing. He pointed out subtle changes that define form. It made a big difference.

My main undergraduate teacher at NIU was Richard Beard who had been a student of Thomas Hart Benton. He tried to send me to Disney. It was a road not taken.

Brown: You are a videographer, photographer, illustrator, documentary filmmaker, graphic designer, and artist. Describe which role(s) or talent is primary/dominant?

Freeland: I have lived the life of an artist. At different times I have worked in different mediums but they are all tied together. Currently, I lean toward filmmaking and photography.

When I was growing up there were no women filmmakers and very few women photographers. I didn’t think working in a film was possible for me. When I was in school there were jobs for illustrators so I tried my hand at illustration. Now women filmmakers and photographers are in demand. I have lived the change. Today there is very little need for hand-drawn illustration – everything is digital. But, I am glad that I can work by hand and in the digital world. It is visual art no matter what medium you use.

Brown: I read that you were once a meteorologist. Please tell us about that job.

Freeland: A newspaper caption under a photo of me said “Meteorologist.” Even though I did learn to read some of the instruments, I didn’t study meteorology. I had a good speaking voice and it is accurate to say that I read the weather.

Brown: What are your strengths and how have they helped or hindered your success?

Freeland: I don’t remember a time when I couldn’t draw. From early childhood, I had the ability to put down on paper what I see around me.

Brown: Tell us how/when your Ole Miss “story” began? Who hired you? How long did you work at Ole Miss?

Freeland: I worked for Ole Miss a total of 25 years but they were not consecutive years.

In 1976 when I was a graduate student at Ole Miss, I was hired by the UM Archives and Special Collections to process photographic collections. After I graduated I became a staff member and continued in the same job. I identified, cataloged, and printed many images from the Edward Boyton Collection of 1860 glass plate negatives. Because I had an interest in history and a background in photography this was a good job for me. Identifying glass plate negatives was like looking through a window into the past. The 1860 photographs were published in a catalog “The University of Mississippi: The Formative Years 1848-1906.” I am credited as a Designer and Editor of Photography in the publication. I left the Archives in 1981 to raise a family and run my own studio

Brown: Tell us about your children.

Freeland: I have two children who grew up with the arts. When they were little they played in my studio so I could work and keep an eye on them at the same time. They were both musically talented but choose different careers. My daughter, Sarah Freeland-Simonson, is an architect with Trapolin-Peer in New Orleans. My son, Thomas Freeland, is a chef at Gianna in New Orleans.

Brown: With the various positions you’ve held, describe your most memorable days at work.

Freeland: I returned to work for the University of Mississippi in 1997. There were so many memorable days at work on Campus. It is hard to narrow it down to a few standouts.

In 2001 while working for the University Museum and Historic Houses, I had the privilege of curating the “WWII Memories” project. I knew about WWII from an early age. My mother’s first cousin was/is MIA aboard Oklahoma lost during the attack on Pearl Harbor. My interest in history and background in photography helped me assemble the exhibition. Almost every day a new WWII artifact, photograph, or story was put in my hands. As word spread among the Veterans, the WWII Memories exhibition grew beyond expectations. The history collected for the exhibition was—and remains—unforgettable. Many of their stories were published in a catalog of “WWII Memories.” The exhibition and catalog received national recognition. Over the years I have received numerous awards but the one from the American Society for the Preservation of State History is the one I am most proud of. My student intern at the museum was Anna Sayre, currently a senior designer for the UM Division of Outreach.

When the exhibition closed, the WWII Memories collected found a permanent home in the University Archives and Special Collections. While working on this project I came to personally know men and women who came of age in the 1940s. I understand why they are often described as “The Greatest Generation.” In 2004 I privately produced a 410-page book, Til’ Then… WWII love letters. Theater Oxford produced a play based on the book. The letters were converted into a script by Alice Walker. Copies of both are in the UM Archives.

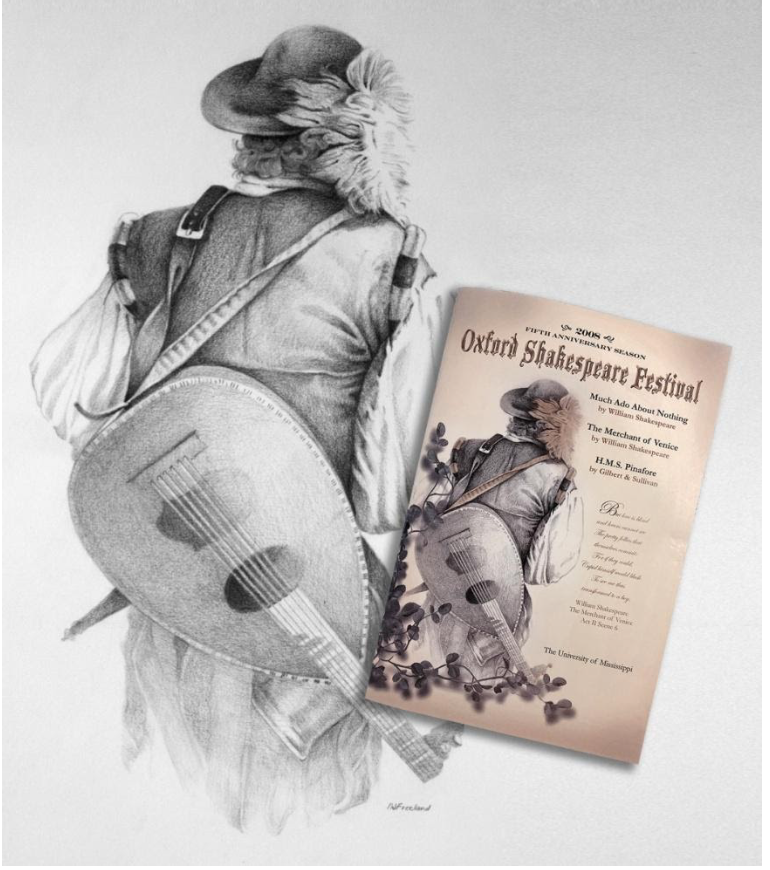

I began working as a Graphic Designer and Videographer for the Marketing Department in the UM Division of Outreach. I couldn’t have asked for a better working environment. I was assigned a number of great projects and given the freedom to be creative. Of the dozens of projects, I worked on two standouts.

I directed and edited “The Road to San Mateo,” a documentary about building a road on the Island of Ambergris, Belize. The project took on a life of its own. The road began as a UM student service-learning project under Dr. Kim Shackelford. It culminated in bringing together a community to build a much-needed road. A workday for me on this project consisted of filming interviews, collecting photographs, and documenting the roadwork in progress. It was anything but typical. Filming in Belize was an amazing experience. Morgan Freeman generously lent his rich voice as the documentary narrator.

While working for Outreach, I created illustrations, graphics and promotional videos for the Oxford Shakespeare Festival. The Festival brought a large group of artists, actors, set designers, costume designers, swordsmen, musicians, dancers, filmmakers, and photographers all under the direction of Joe Cantu. It was exciting to work with so much talent.

Back row: Vanessa Cook, Anna Sayre, Larry Agostinelli, Pam Starling

Front row: Kris Zediker, Deborah Freeland, Janey Ginn

Brown: In your opinion, what attributes/traits predict success in life?

Freeland: Resilience.

Brown: What do you like to do for fun?

Freeland: Host dinner parties for my friends consisting of good food, good wine, and good conversation.

Brown: What is your favorite quote or expression?

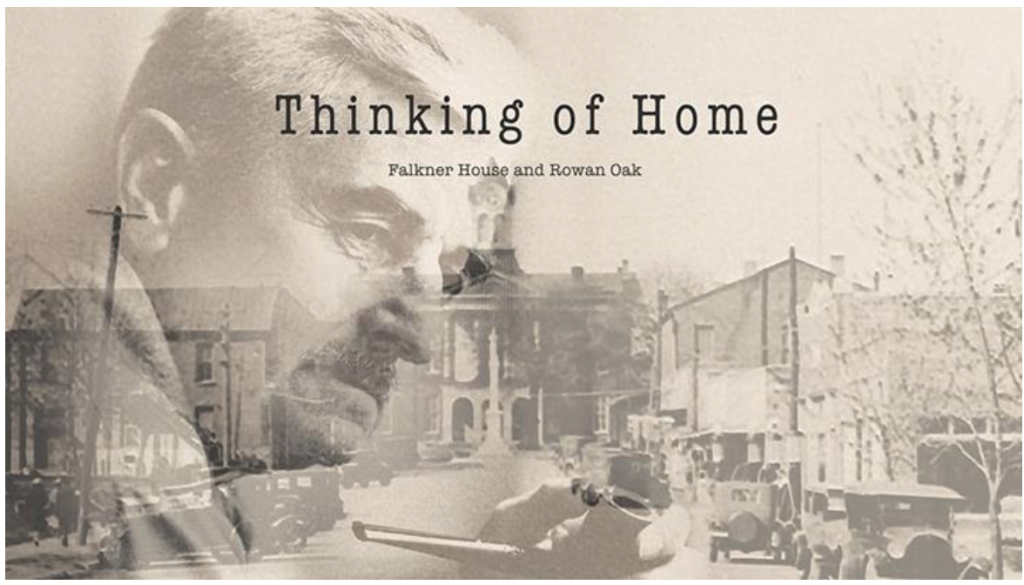

Freeland: “Between grief and nothing, I will take grief.”- William Faulkner

At my age, I think I understand what Faulkner meant.

Brown: If there was something in your past you were able to go back and do differently, what would that be?

Freeland: Finish a Ph.D.

Brown: What do you do when you’re feeling stressed?

Freeland: Play my baby grand piano.

Brown: Tell us something about yourself that not many people may know.

Freeland: My Dad was attending a conference in Dallas on November 22, 1963. On this rare occasion, he had taken the family with him. In the morning he told me that when his meeting broke for lunch he would take me to see the President. I was a child in a crowd waiting to wave at Kennedy when he was assassinated.

I have cousins that were performance artists in very different ways–Molly O’Day and Blaze Starr. Ha!

Brown: What are you most grateful for in life?

Freeland: Good health. If you have good health you can figure out the other stuff.

Brown: What has become your routine since you retired? Do you have hobbies?

Freeland: I am no longer working at the university but I don’t feel like I have retired. I am always looking for the next project to put down on paper or story to capture on film. I have finished two portraits and created graphics and dust jackets for a set of oral history books – recently gone to press.

John Cofield was kind enough to ask me to sign books with him at Southside Gallery in conjunction with an exhibition of my Vintage Oxford photographs.

Last year I had the pleasure of working as director/editor on a documentary film “Thinking of Home, Falkner House and Rowan Oak.” It screened on PBS and WKNO last November. I am excited that the film is in the running for a regional Emmy.

Brown: To quote Katherine Meadowcroft, Cultural activist and writer, “What one leaves behind is the quality of one’s life, the summation of the choices and actions one makes in this life, our spiritual and moral values.” What is your legacy?

Freeland: I like the Meadowcroft quote. There is truth in it.

A career legacy is something you don’t really know but I hope I have added to the regional arts and to the preservation of southern history.

Bonnie Brown is a retired staff member of the University of Mississippi. She most recently served as Mentoring Coordinator for the Ole Miss Women’s Council for Philanthropy. For questions or comments, email her at bbrown@olemiss.edu.

Sign up to receive Hottytoddy.com morning and evening headline emails HERE!

Follow HottyToddy.com on Facebook (If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…), Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat (@hottytoddynews).