By Jeff Roberson

Hottytoddy.com contributor

robersonjeff0630@gmail.com

Coolidge Ball remembers the moment his heart believed attending Ole Miss was acceptable.

No African-American man or woman had ever played sports for the University of Mississippi. Ball, an all-star high school basketball player in Mississippi in the late 1960s, was moving through uncharted waters as he moved toward his decision.

“I was a senior in high school, and I remember a recruiting trip to Ole Miss,” the Indianola native said of a February, 1970, Ole Miss men’s basketball game against Kentucky. “(UM assistant coach) ‘Cat’ Robbins came down to see me play a couple of times, and he asked me if I would like to come up for a game. I told him I would.”

So Ball made the drive to Oxford with some family and friends for the big game.

Imagine for a moment that journey. Only eight years before, James Meredith had been admitted to the University as the first African-American student.

History tells us, as do many still in our midst, that it was an era in the South of stress and strife, injury and even death.

For Coolidge Ball and his entourage, they were not on a road less traveled. They were on a road never traveled.

The Crowd Goes Wild

Ole Miss had not been a consistent winner in men’s college basketball. At the time there was even no women’s program, but that was the case at most Division I schools, especially in the South.

The fact is, despite having a lot of talented players through the years, Ole Miss really hadn’t tried to win big at men’s basketball, as hard as that might be for some to believe. All the resources toward winning championships went to football. The same school year Ball made his visit, Ole Miss played in its eighth Sugar Bowl in 18 seasons.

But basketball was Ball’s sport, and Ole Miss wanted him. So he came to the Kentucky game to check things out.

“Back then, they could introduce recruits at halftime,” Ball said.

And not just introduce them but have them stand on the court and recognize them.

Take a moment to absorb that as well.

That meant the name Coolidge Ball would reverberate throughout the Rebels’ basketball home, C.M. “Tad” Smith Coliseum, as fans watched and listened.

How would that historic moment go? What would the reaction be? How would Ball handle whatever might happen?

Ball remembers another factor that added to the suspense.

“(Ole Miss) had also brought in a white kid from Louisiana they were recruiting,” he said. “They had asked me for my stats. I knew what they were going to do.”

Halftime arrived. Ball and the Louisiana kid got up from their seats.

“I walked down onto the court, and it was going to be a moment to see how things would go,” Ball said, recalling it vividly. “I actually wanted to make that comparison. I thought the response would at least tell me something about whether or not I would be accepted by Ole Miss people.”

The comparison would be easy. Two players. Two introductions. One moment.

Ball waited.

“They read the other player’s stats out and called his name,” Ball said.

There was applause and there were cheers. No surprise there. This was a recruit Ole Miss wanted.

Ball was next.

“They read mine. ‘Coolidge Ball from the Magnolia State.’ The crowd just went wild,” he said. “Maybe it was because I was from Mississippi.”

Maybe. But surely it was also because Ball was a standout high school player who could make a difference for a Rebel program that had never been crowned a champion, at least as far back as the founding of the Southeastern Conference in the early 1930s.

Making an Impact

After the game, Ball and his family and friends started the drive back home to Sunflower County, deep in the heart of the Delta.

“I remember going home that night and somebody in the car saying, ‘Coolidge, you got a better ovation than the white kid did.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I noticed that.’”

He didn’t forget it. He also remembered the current Ole Miss players visited with him that night, too. And that was important.

“Freshmen couldn’t play with the varsity back then,” said Ball of a NCAA rule which changed during his time at Ole Miss to allow freshmen to play immediately with the varsity. Schools even had freshmen games for those players before the varsity game to follow.

“I remember Danny Gunn and some of the other freshmen players coming over to talk to me after their game,” Ball said.

Ball felt good about the visit. He wasn’t sure that he would, but he did.

“I felt I could make an impact, and I wanted to go somewhere I could do that,” he said.

But would that be Ole Miss, the flagship institution of his home state?

This wasn’t a unique situation to the University of Mississippi. During this era practically all historically white colleges and universities in the South were changing to include black students and athletes.

Heading West

Sam Lacey was a terrific player for Gentry High School in Indianola in the mid-1960s. Gentry was the African-American school when public schools in Mississippi were segregated. Lacey chose to play college basketball at New Mexico State. Ball and Lacey knew each other from their hometown.

“Sam Lacey, my home boy, had finished high school in 1966 when I was entering high school,” Ball said. “He was a 6’11” guy. His senior year at New Mexico State they were like third in the country behind UCLA and St. Bonaventure. I came along and Rob Evans recruited me for New Mexico State when I was in high school.”

Evans, an African-American, was an assistant coach at NMSU and had played basketball there.

Ironically, in the 1990s, Evans became the head coach at Ole Miss.

Rather than going to Ole Miss for college, Ball chose New Mexico State, just like Sam Lacey had done. But he left the door open to return.

“I told my mom that if I didn’t like it, I definitely would be coming home,” Ball said.

He stayed in Las Cruces, New Mexico, for a few weeks in the summer of 1970. But he wasn’t comfortable.

“It was a different world out there in the desert. I had signed a scholarship paper, but I hadn’t signed a national letter of intent.”

That was very important. It meant he could leave and play right away at another college.

His hometown newspaper in Indianola, the Enterprise-Tocsin, wrote a story about Coolidge Ball, his talents, and his decision to head West.

“Another Sam Lacey,” the story said.

Ball wasn’t all that pleased with a headline like that.

“I wanted to be my own guy.”

A Better Fit

In July, 1970, Ball made a phone call.

“I called Coach Robbins. He was at a camp over at Northeast (Mississippi Community College). I asked him if (Ole Miss) had a scholarship left, and he said ‘Yes.’ I told him I didn’t think I was going to stay at New Mexico State. He asked me if I had signed a national letter of intent. I told him I had only signed a scholarship paper, not a national letter.”

Ball decided to play basketball for the Ole Miss Rebels.

“Some people thought it might be better to go to New Mexico State because of what Sam had done there,” he said. “He was (a first round) pick in the NBA draft. But I always kept Ole Miss in the back of my mind, because I felt like Ole Miss would be a good fit for me, and I could make an impact on the program here at Ole Miss.”

In August, 1970, Ball returned to Mississippi. He enrolled at Ole Miss, just like all other student-athletes had done before him who played for the Rebels.

But there was one difference. He was black.

Ball knew he was blazing a trail. He knew the story of James Meredith and the door that had been opened by him.

“This was only eight years removed from James Meredith enrolling to me enrolling,” Ball said. “My decision was pretty much based on the ovation, the applause, and the support I got out there that night when Ole Miss played Kentucky on my recruiting visit. If you have your coaches, teammates, and fans supporting you, I wasn’t worried about anything else.”

Ball quickly admits his time at Ole Miss was good and that there were no problems with anything concerning his race.

“I got treated just like any other 18-year-old freshman on campus,” he said. “It was just a great fit for me.”

‘In My Mind it was Ole Miss’

In January, 2016, the fabulous new Pavilion at Ole Miss opened. Only a few thousand seats short of being the equivalent of most NBA arenas, it has all the amenities and glitz of those spectacular buildings.

Soon after its opening, an honor was bestowed upon a Rebel who had lifted his teams at the old coliseum not all that far away on campus.

Coolidge Ball was honored with his own plaque at the entrance to the Pavilion. Fans will always be reminded that once upon a time Ball had done what no man of his race had ever done.

He had heard 50 years earlier from a lot of skeptics.

“Some people found out I was coming back home to go to school at Ole Miss, and they’d say, ‘Are you nuts?’”

Ball laughed at that. He told them then what many hear today.

“I’d say ‘Have you been to Ole Miss?’ and they’d say, ‘I haven’t but I’ve heard.’ And I would tell them they needed to visit to find out for themselves.

“And I asked God to direct me where I needed to go. In my mind it was Ole Miss. He was leading me. I chose Ole Miss. And it was good for me to go out to New Mexico State first, because that clearly made up my mind to come back home and go to Ole Miss.”

‘That Was Me’

Ball was later joined by black student-athletes Dean Hudson and Walter Actwood on the Ole Miss basketball team. In football, Ben Williams and James Reed soon chose Ole Miss to become members of that storied program.

But it was Coolidge Ball who was first.

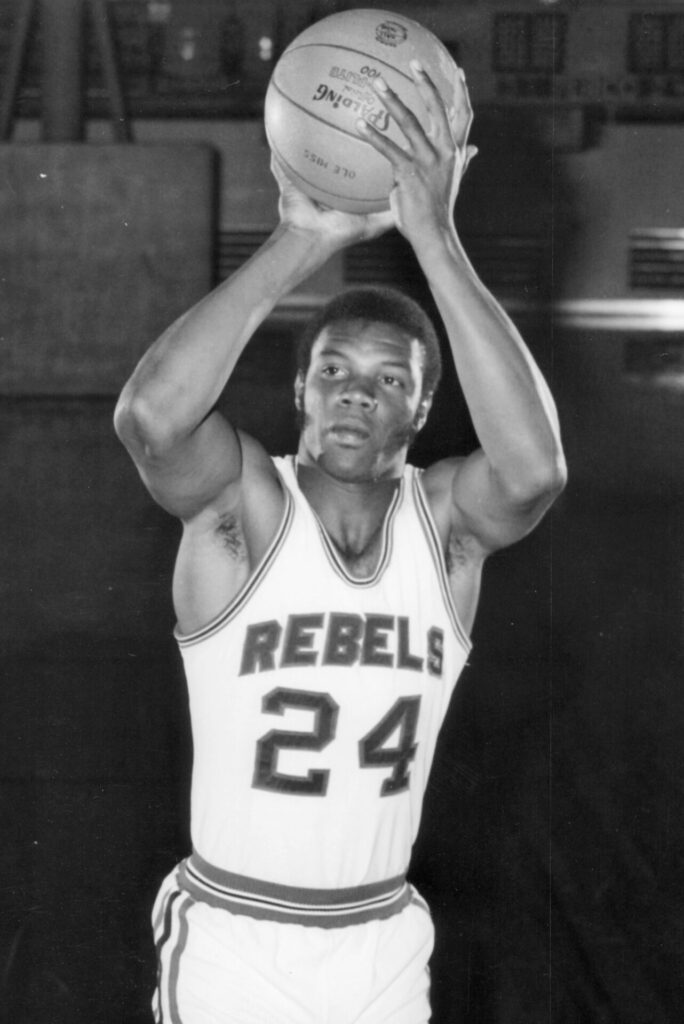

He scored 1,072 points during his three varsity years, the Rebels had three consecutive winning seasons for the first time in more than 30 years, and he was named team captain and most valuable player.

“After I finished at Ole Miss, I went to Hamilton, Ohio, to play for a year in what they called the International Basketball Association. The IBA. I stayed up there a season. In March that year, I came home to Mississippi. I finished school that summer, which was in 1975. I got my degree in recreation leadership and a minor in art.”

Today Ball continues his work as an artist, a sign painter, and a graphics expert. He travels to arts and crafts shows as well as other events to sell his products.

Sometimes he’s even recognized as a former Southeastern Conference basketball player, since many of his travels are in the South. Normally he’s kept that to himself.

“I remember one time in Decatur, Ala., at a horse show, I told them I would not be there on Saturday but would be there on Sunday,” he said.

The people in Decatur found out Ball was being honored at his alma mater that Saturday with induction into the Ole Miss Athletics Hall of Fame. The following day Decatur honored him, too.

“They called me down to the middle of the arena at the show and introduced me, and they read the information on me from the brochure,” he said. “People were coming up and saying things like, ‘Coolidge, I’ve been knowing you all these years and I didn’t know you were a college basketball player at Ole Miss. You didn’t even tell us.’ I’d say, ‘Yes, that was me.”

Coolidge Ball still lives in Oxford with his wife, Ruth, and they enjoy it when their children, Anthony and Telitha, visit them. Anthony lives in Arkansas. Telitha lives in Desoto County. Anthony has two sons, Mason and Marion.

Ball remains quite proud of the plaque on the wall of the Pavilion porch.

“I’m thankful for it. I took my grandkids by there and showed it to them. They’re excited about it. It’s a warm honor, a great feeling, to have something like that. And I thank Ole Miss for it.”

Those thanks, both for the trailblazer from Indianola and for his University, obviously go in both directions.