Arts & Entertainment

Allen Boyer: Review of “Fortunate Son: The Story of Baby Boy Francis,” by Brooks Eason

Fifteen years ago, Paul Brooks Eason fielded a telephone call out of the blue. Reared in Tupelo, practicing law in Jackson, he had long known he was adopted – but he had no reason to suspect that a court in New Orleans might order a nationwide search for him.

Eason sums up the story with a lawyer’s matter-of-fact tone.

Brooks Eason, author of “Fortunate Son: The Story of Baby Boy Francis.” Photo provided.

“Two wills, one executed by a rich man and the other by his granddaughter, are central to the story. The first, signed in 1962, contained a clause that was likely an afterthought, was never intended to take effect, and never did. And yet, more than four decades later, the clause almost made me a wealthy man, a result that the man who signed the will never could have foreseen . . . . Nor did his granddaughter intend to make me an heir. To the contrary, she sought to disinherit me. But, as fate would have it, she nearly achieved the opposite.”

The calmness of this meditation is deceptive. Its loose, knowing phrases sum up the chances and ironies that the history of a family involves. And this is a book about the care taken by lawyers and the pulse of family life.

“Fortunate Son” winds together the two strands of Eason’s family history. On one side, he descends from small-town bankers, aldermen, and church-going Methodists. (Readers in Tupelo will recognize many faces here.) The other side of his lineage traces back to a family that prospered on Oklahoma oil. Unusually, the unwed mother at the center of this story was wealthier than the parents who adopted her child.

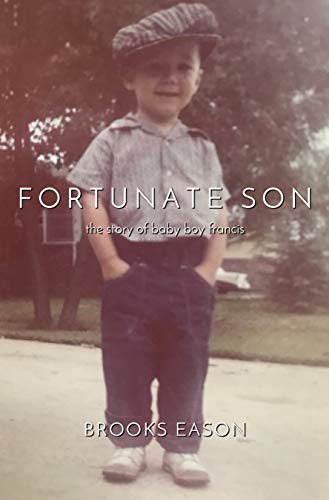

Cover of “Fortunate Son.” Photo provided.

Julie Francis was the teenage girl who gave birth to Eason. She had dropped out of Washington University in her freshman year, to spend months in New Orleans’ Methodist Home Hospital, a facility for unwed mothers. Eason was glad to hear that Julie could be exuberant and loyal to close friends. He does not conceal that she suffered two failed marriages, drank too much and knew that she drank too much, and died, aged 47, from cirrhosis of the liver.

Julie’s last will and testament left one single token dollar to an unnamed person. “In July 1957, in New Orleans, Louisiana, I gave birth, out-of-wedlock, to a male child who was subsequently adopted by a person or persons unknown to me,” she tersely provided. But Julie was the beneficiary of a family trust, and thereby hangs the tale. The family lawyers who prepared her grandfather’s will did not provide that Julie’s interest, when she died, would go “to her estate” or “to the beneficiaries of her will.” Instead, they used a close synonym, “to her issue.” That particular phrase made it essential that her unknown son be identified.

“Fortunate Son” is distinguished by its clear-eyed awareness of how familiar themes recur across generations. (Julie’s out-of-wedlock pregnancy is not the last unplanned pregnancy in the family, and the author’s male forebears are often drawn equally to respectability and recklessness.) Eason also ponders, without sentimentality, how a single life may be a study in irony. If a prodigal child remakes a career, which matters more: that a respected Methodist minister had once served three years in prison, or that a high-living young man learned a lesson and left a crooked past behind?

This is a memoir, Eason warns his readers. And his narrative is packed with the stuff of genealogy, dates and locations and occupations and family gossip. But if this book is fond and loving, it is also warts-and-all.

“Fortunate Son: The Story of Baby Boy Francis.” By Brooks Eason. WordCrafts Press. 254 pages. $29.99 hardback, $15.95 trade paper.

Allen Boyer is Book Editor for Hottytoddy.com.