Featured

Oxford Pride Series: Igniting a Queer Liberation in the Deep South

By Talbert Toole

Lifestyles Editor

talbert.toole@hottytoddy.com

Fifty years ago in 1969, the riots at The Stonewall Inn would challenge societal norms, the marginalization of people who identified as LGBTQ and strike a fire in liberationists to demand civil rights throughout the country.

As the LOU community celebrates its fourth Oxford Pride this week, this year’s theme pays homage to the trailblazers of the Stonewall Riots who parted the waters for diversity and inclusivity.

Although the riots at the famous Inn—located in New York City—are mostly credited with sparking the movement for LGBTQ acceptance, what tends to be overlooked is the bountiful activists who created spaces for LGBTQ people, specifically in the South, during that time period.

In part two of the “Oxford Pride Series,” Hottytoddy.com continues to explore the lost voices Hooper Schultz unearthed in his thesis that looks into the lives of queer activists in the South.

Schultz, University of Mississippi graduate student, recently defended his thesis that explores the history of gay liberation movements in the Southeast. Hottytoddy.com spoke with two activists in the South that Schultz’s interviewed for his thesis: Dan Leonard and Dave Hayward.

Hayward, an Atlanta, Georgia resident, began his journey of gay activism in the South in Washington, D.C.; however, after a post-graduation trip to “The City Too Busy to Hate,” Hayward was not only a witness to the first Atlanta Pride parade but an organizer of the event, as well.

Igniting a Queer Liberation in the Deep South

The New York City Police raided The Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969, known as a place for members of the LGBTQ community to gather, dance and immerse in a shared experience.

As bricks and Molotov cocktails were thrown in an uproar, the police flooded the bar on grounds of immorality. This time, those in the bar fought back. The riots garnered national attention and eventually lit a fire underneath several other LGBTQ communities, including one in Atlanta, to organize movements which would become known as Gay Liberation Fronts (GLF).

Hayward, originally from New Hampshire, moved to Washington, D.C. in 1967 shortly after the Stonewall Riots to attend Geroge Washington University.

While attending the university, Hayward had the realization it was time to immerse himself in the queer community and come out as gay.

Having knowledge of Mattachine Societies—founded in 1950, the society was one of the earliest LGBT (gay rights) organizations in the United States—Hayward contacted the D.C. chapter that leader Frank Kameny spearheaded.

Kameny became a widely known gay activist and forefront runner of the LGBTQ Rights Movement after being fired from his government job in 1957. After his firing, Kameny appealed to the court system. His case would move to the highest of the land, the Supreme Court; however, the court refused to hear his case. But the LGBTQ community dubbed him an activist for fighting for equality, the most revered title one could have.

When Hayward contacted Kameny, he confessed being a homosexual made him feel bad.

Kamey asked Hayward a question many in the LGBTQ community are forced to answer directly, “Why?”

“For a minute, I was speechless because I understood what he was saying,” Hayward said.

Hayward said Kamey gave him the answer he sought: “You do not need to feel bad about being a homosexual, you just are.”

Dave Hayward, on the right, moved to Washington, D.C. to attend George Washington University in 1967. Photo courtesy of “Touching Up Our Roots.”

That moment became the real turning point in Hayward’s life, he said.

Prior to the Stonewall Riots, a plethora of demonstrations filled the streets of Washington. From Civil Rights to the Vietnam War, protestors gathered in front of the White House to demonstrate their opposition on several issues. Though all represented positive change, from his viewpoint, none represented the gay rights movement until the riots at the Inn.

Slowly, a movement known as Gay Liberation Fronts began to spread throughout different cities in the U.S.

“The main thing about Stonewall (riots) is that it created all kinds of groups,” he said.

In January of 1970, Hayward among others formed a GLF in Washington. One of the major successes of the Washington GLF was the creation of small groups where members could discuss a variety of topics. The discussions would now be considered ‘queer theory,’ according to Hayward.

As Hayward continued his work with the GLF, he said one of his first major gay activist moments was actually working for Kamney. In 1971, Congress decided it would have a representative from the District of Columbia in the House of Representatives. Kamey decided to run for that office. Approximately fourteen candidates ran for the position, including Kamey, an openly gay man.

Although Kamey lost, he came in fourth for the office.

Continuing to Fight the Fight

After graduating from college, Hayward moved to Atlanta, Georgia in October 1971 where he would continue his work in GLF. Hayward’s first meeting with the GGLF took place in a bookstore what was once known as the Midtown area of Atlanta. When he walked into the meeting he was shocked; the group was less diverse than the Washington front.

As he joined the meeting, a man dressed in a three-piece charcoal suit by the name of Bill Smith chaired the meeting. Another member helped chair the meeting by the name of Severin (also known as Paul Dolan), a gender fluid member, who Hayward considers the first transgender leader of the GGLF.

The front took on several issues head on through the early seventies including a gay educational committee at the University of Georgia. Hayward recalled his time visiting Athens, Georiga, the home of UGA, where several protests took place in opposition of the educational committee that continues today.

“That was some of our biggest efforts,” Hayward said.

Shortly after the Stonewall Riots, a similar event would spark the creation of the Georgia Gay Liberation Front—a movement to include all LGBTQ in the Peach State.

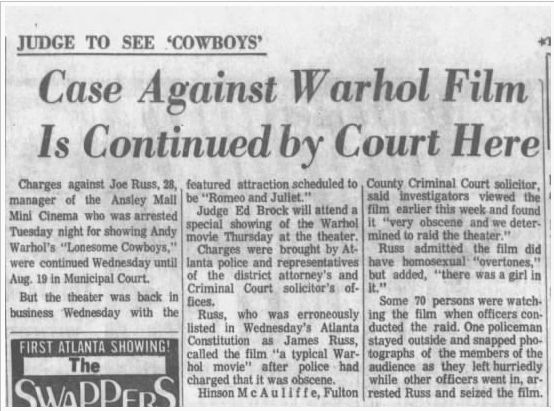

What was known as the Ansley Mall Mini Cinema in Atlanta, showed an Andy Warhol movie “Lonesome Cowboys” August 5, 1969. The film had a particular long sex scene which exposed two men and a woman. The Atlanta Police Department raided the theatre due to the exposure and what was deemed queer content.

Hayward had two friends in attendance of the film during the night of the raid. Approximately 70 patrons of the theatre were interrogated and photographed by the APD. The raid was considered the Stonewall of Atlanta and ignited liberationists to create the GGLF, according to Hayward.

The raid became the catalyst for the GGLF to form, Smith later told Hayward.

The raid was a catalyst for the GGLF to form, Smith later told Hayward.

Paperclipping courtesy of Newspapers.com.

In 1971, the GGLF decided to organize the first gay pride of Atlanta. Smith, who straddled two different worlds because of his connection with the GGLF and having a job at City Hall, was denied the permit to march the streets of the city. However, the organization persisted.

The group marched without the permit, according to Hayward. Those who joined forces could only march on the sidewalks and had to stop at each stoplight.

The following year, the GGLF again began organizing another pride march. However, even the known gay clubs resisted giving the group support, especially two well-known clubs: Sweet Gum Head and The Cove.

After being denied to advocate for the march at SGH, the group moved onto The Cove. Hayward said he remembered the club being more hostile than the other, so he decided to place leaflets on car windshields while his friends entered the bar.

As he stood in the parking lot, Hayward said he remembered seeing his friend tossed out through the saloon-like doors of The Cove for attempting to advocate club attendees to join the movement.

Charlie St. John, a member of the GGLB who Hayward described as fierce, was the member to march down to City Hall for the permit.

The group faced resistance even from their own community, but it still rose to the occasion. Over 500 allies and community members marched through the streets of Atlanta chanting “What do we want? Gay rights! When do we want them? Now!”

As a result of a successful gay pride march, the Atlanta mayor at the time, Sam Massell, appointed an openly gay person to the Atlanta Community Relations Commission: Charlie St. John.

St. John was a member that helped lead the organization to the forefront. However, due to his continuous activism, he also faced severe backlash from the police. As someone who was completely against the use of contraband, according to Hayward, St. John would have never had drugs in his apartment. Still, the police department raided his apartment for drugs which eventually led to his landlord ousting St. John from his apartment in the Virginia Highlands neighborhood.

The End of an Era

Through backlash, hostility and much success, the Georgia Gay Liberation Front came to a close in 1973.

During a meeting after a successful pride in ’72, Smith and Severin clashed in how the group would advocate for the LGBTQ community. Smith was someone who would be than willing to attend City Hall meetings in order to move forward with equality, according to Hayward; however, Severin saw a different way to approach the situation. Severin was a person who would rather perform demonstrations and protests in order to spread the message the organization sought to convey, Hayward said.

Members who agreed with Severin departed while those who agreed with Smith remained.

Being friends with both Smith and Severin, Hayward decided to still be apart of the organization, but it still fell apart.

“The organization never really quite recovered [from the fight],” Hayward said.

Although the organization had faced a crossroads, it had enough members and energy to form one more pride march in ’73 before dissolving.

Liberation in the Face of the Enemy

It has been nearly 50 years since Hayward and his brothers joined forces and struck a chord with the LGBTQ community in the bustling city of Atlanta. From raids to protests and marches, the GGLF faced many oppositions to defy the impossible in order to create a queer place for all.

Hayward continues his liberation efforts through “Touching Up Our Roots“— a grassroots community effort to preserve Atlanta’s LGBTQ history. He serves as the coordinator of the non-profit. Touching Up Our Roots is an incorporated non-profit in the state of Georgia registered with the Georgia Secretary of State.

However, Hayward said there is a new enemy the LGBTQ community faces in the attempt to continue the journey he helped organize so many years ago.

President Donald Trump.

“What [the LGBTQ community] have in common is an enemy,” Hayward said. “The Trump administration.”

Although the Trump presidency has squandered several civil rights, such as soldiers who identify as transgender from serving in their respective branches of the military, Hayward said he does find it heartening that the LGBTQ community does in fact still have many of its basic rights in today’s day and age.

“We have more than one foot in the door,” Hayward said. “In terms of having everything taken away, that is not going to happen.”

Hayward said the community must continue to band together and protect one another, especially the community’s transgender members.

“It’s really important we stay vigilant,” Hayward said. “Keep on keepin’ on.”