*Editor’s Note: Lovejoy Boteler, author of “Crooked Snake: The Life and Crimes of Albert Lepard,” will read and sign copies of his book on Thursday, March 21, at 6 p.m., at Off-Square Books, in conjunction with a broadcast on Thacker Mountain Radio.

If you enjoyed “Cool Hand Luke” and “O Brother Where Art Thou” – if your vision of the South includes a deputy sheriff whistling cheerfully to his trusty bloodhound – then you are primed to appreciate Lovejoy Boteler’s true-crime book “Crooked Snake: The Life and Crimes of Albert Lepard.”

“Crooked Snake” is an unusual study, part biography and part memoir. Albert Lepard was born in 1934 and shot dead in early 1974, fifteen years after being sent to Parchman, an institution from which he escaped six times. Lovejoy Boteler acknowledges his peculiarly personal connection to his subject:

“I don’t know how many people were kidnapped in Mississippi in 1968” he observes, “but I was one of them. I was taken from my family farm that June by two escaped convicts from Parchman Penitentiary – John Parker, convicted of armed robbery, and Albert Lepard, sentenced to life for murder.”

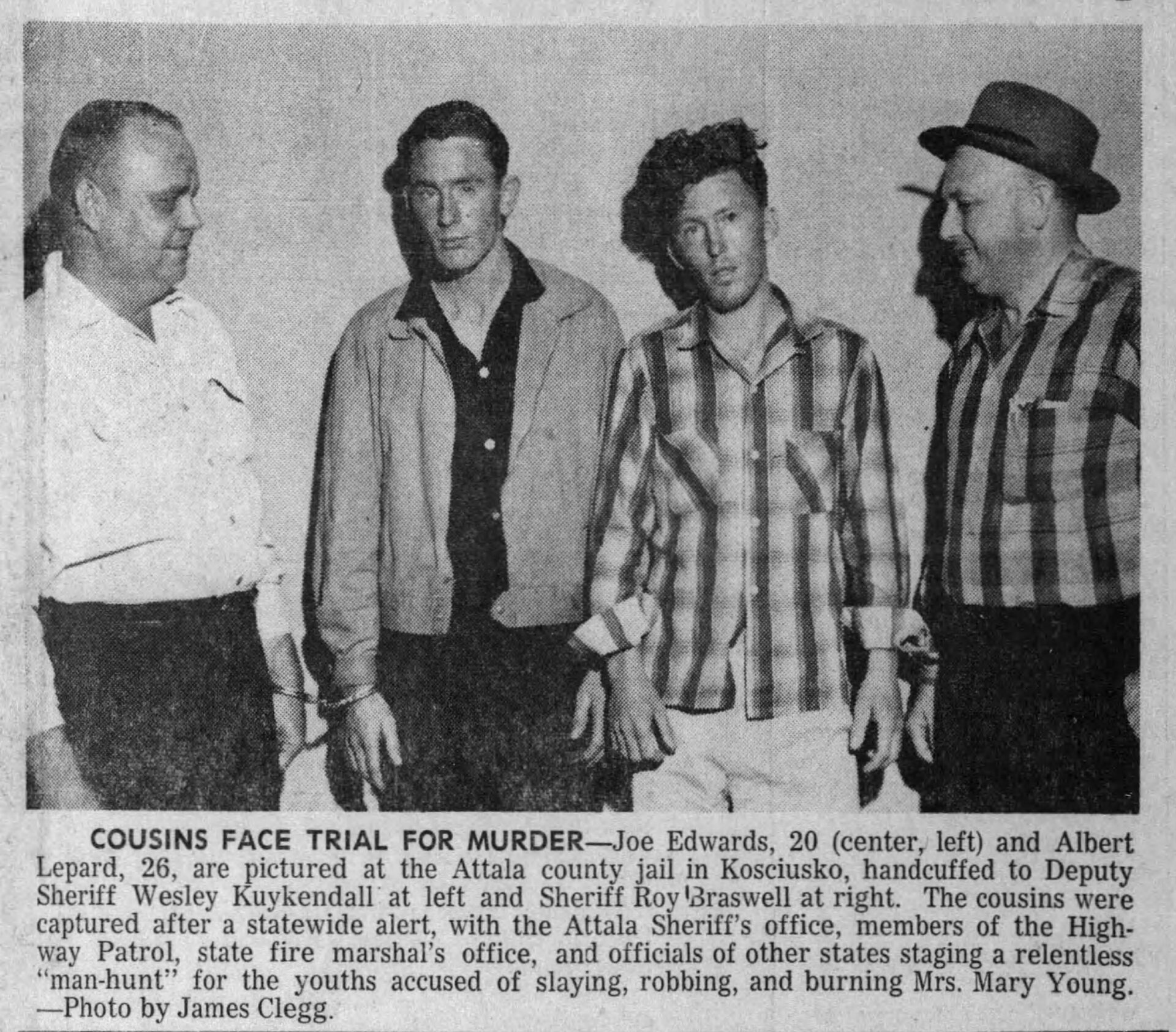

Albert Lepard was reared on the hardscrabble side of Attala County, on Seneasha Creek. (Seneasha descends from the Choctaw word meaning “crooked snake.”) He was sentenced to life in prison in 1959. He and a cousin pistol-whipped and robbed an elderly lady, his mother’s aunt, then burned down her house around her. Lepard spent the rest of his short, hot-headed life at Parchman – whenever he was not on outside it, on the run.

In early 1961, after returning from a Christmas furlough, Lepard made his first escape, a headlong dash down the freezing Sunflower River. He reached his brother-in-law’s farm at Zumbro Plantation. His relatives took him in, then called prison officials. They captured Lepard asleep in a hay barn.

In late 1963, during his most spectacular escape, Lepard and a fellow inmate drove around the country for four months: to Florida, Virginia, Michigan, Kansas and California. By Christmas Eve, Lepard was home in Attala County. His uncle called the sheriff, a highway patrolman set up a roadblock, and Lepard was back in Parchman by Christmas morning. Breakfast was scrambled eggs with blackstrap molasses.

In the summer of 1964, Lepard was again at large. This escape ended with little fanfare. With race riots in eastern cities, civil rights workers killed in Neshoba County, and American troops arriving in Vietnam, little coverage was given to a local news item, “the story of a wild shootout in the Mississippi Delta at Hopson Plantation between a Parchman posse and four escaped convicts. Two were killed.”

In June 1968, a stolen pickup truck carried Lepard and inmate John Parker to Riverdale Farms, just outside Grenada. They walked up to a field where eighteen-year-old Lovejoy Boteler was working. They begged a drink of water, badgered him into giving them a lift, stuck a pistol in his ribs, and took him along as they drove to Memphis. Then they turned Boteler loose, and, enigmatically, gave him money as they parted: a handful of dollar bills, and two silver dollars hidden in the pickup truck’s glove compartment.

Lepard was known for his crazy shock of red hair. “Pound for pound, Albert was about the toughest guy I ever seen,” a prison guard remembered. He sent one inmate to the hospital because the man had cussed him out; he tried to stab another inmate because he thought the man had slighted Loretta Lynn. Lepard was illiterate, until the prison camp intellectual, Ku Klux Klan bomber Tommy Tarrants, taught him to write his name. Tarrants also tried to coach Lepard for parole hearings. That never worked. “After one particular hearing, Lepard was returned to Maximum Security in the back of a truck, chained to the roll bar.”

Another convict remembered, “I feel like he was asking to be killed. I really do. He just kept escaping and escaping and I knew he wasn’t gon’ get away. I told him, ‘You know they’re gon’ kill you.’”

This is a sharp, unsentimental book, and it deserves a good audience. Boteler has interviewed dozens of witnesses and dug through newspaper morgues in Mississippi and Tennessee. “Why you chasin’ a ghost?” one interviewee asked him. “Sometimes you have to catch a memory to let it go,” he replied.

People in the Delta will recall Lepard; so will people in Attala County, and Scott County. It was in a country store north of Forrest that Lepard died, very much as he had lived, yelling and cursing and pointing his pistol at a storekeeper who already had him covered with a shotgun. Mississippi lawyers – generations of them – will also remember Lepard. When charged with murder in 1959, Lepard was defended by a novice attorney from Kosciuscko. New to criminal law, but able and quick-witted, he weighed the odds and talked Lepard into pleading guilty. That young lawyer, who went on to discuss his first case across decades of law school classes, was Ole Miss law professor Aaron Condon.

“Crooked Snake: The Life and Crimes of Albert Lepard.” By Lovejoy Boteler. University Press of Mississippi. 224 pages. $25

Allen Boyer is the Book Editor of HottyToddy.com. A native of Oxford, he worked twenty-four years for the New York Stock Exchange Division of Enforcement.