Headlines

Letter to the Editor: Your Southern Pride is Oppression

Contributed by Alysia Burton Steele

School of Journalism and New Media Assistant Professor

alysia@go.olemiss.edu

The story is about me, my paternal grandparents, and the emotions that swooped in as I thought about how my life could have been drastically different if we were in the wrong place at the wrong time in rural Pennsylvania in 1988. And, all I could do was cry as I shared details about a painful memory with my husband; something I haven’t talked about or processed in 31 years.

Alysia (middle) with Pop-Pop and Grandma at her high school graduation in 1988. Contributed photo.

In a time when our country is divisive about race, class, gender, labor, truth, accountability, and freedom of expression, I hope something shared here today will help advance the narrative about the powers of Confederate statues on college campuses, the messages they send and the people who feel protected enough to cause emotional terror on a college campus supporting them.

This week, my husband and I watched the hour-long documentary “The Green Book: Guide to Freedom” on the Smithsonian Channel. It’s not about the Oscar-winning movie, but the actual book, and how it came to be. I wasn’t in the mood to watch something heavy. I preferred to zone out watching one of our favorite shows. I’d had a long day of grading photojournalism assignments and meeting with my history professor, as I’m also taking my first doctoral history class at the University of Mississippi, a school also known as Ole Miss.

My professor and I met at a local coffee shop to go over ideas about a discussion I’m to lead next week in our women’s and gender history class. I was still processing what we’d discussed earlier when my husband and I arrived home and sat down to watch TV.

A woman, who was interviewed in the documentary, talked about her father getting out of a car to make sure it was safe to stop somewhere, as a black person, during the Jim Crow era. I burst into tears.

Wait…I remembered something.

My husband looks concerned as he watches my facial expression shift, and tears swell in my eyes.

“Pause the movie, please,” I asked.

I’d forgotten that as a high school senior in 1988, my grandparents, who were raising me, drove me to Indiana University of Pennsylvania for orientation. It was the college I’d decided to attend, and it’s about an hour outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and three hours from my hometown of Harrisburg – the state’s capital.

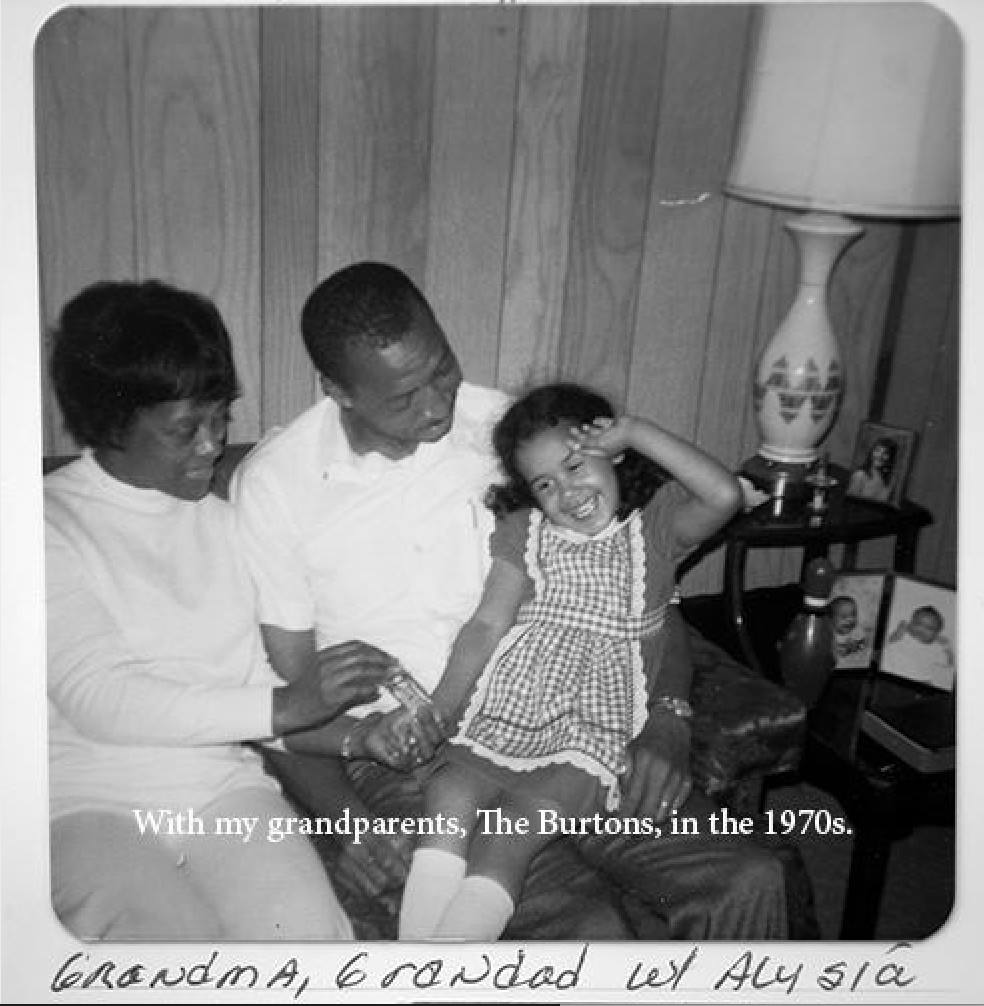

Alysia with grandma and Pop-Pop in the 1970s around the time they gained custody of her. Contributed photo.

My grandfather made a wrong turn and we ended up in a very rural part of the state. I don’t remember where we ended up, but it looked like the typical landscape of farming country in Pennsylvania. Blues skies turned dark, and seen from the middle of a densely wooded area up a small hill was the sign ‘OPEN’ in bright lights. Pop drove our Buick LeSabre up the unpaved road. I was in the back seat, my grandmother on the passenger side up front. As an 18-year old, I cried for Pop-Pop not to get out of the car and walk inside to ask for directions.

I remember saying, “What if something happens to you?”

With tears in my eyes, I opened my car door to follow him. I wanted to protect him. He was 6’2” with a lean body. He worked as a mail carrier, often times coming home with swollen ankles. You see, he was a Korean War veteran with tiny shrapnel pieces still peppered in both ankles after being shot. He walked with a slight limp, never complaining. At one point after military service, he worked three jobs. My aunt Marie, his youngest child, woke him when it was time to head to the vacuum cleaner repair shop.

She didn’t remember how old she was, but said he taught her how to tell time by, “When the big hand is on 12, and the little one on three, wake Daddy…”

One day when I nagged him to tell me about the war, he sucked his teeth and said as a black man he wasn’t supposed to walk through the bus station with his white counterparts but walk around the building. With his blues eyes, back erect, he walked through the station daring anyone to make him walk around the building, for he’d just served over nine years in the Army and was a sergeant. He came home wounded but able to walk.

Pointing his finger at me, he yelled, “Get. Back. In. The. Car!”

I want you to process that for a minute.

My family didn’t talk about ‘Sundown Towns’ or how they couldn’t shop somewhere. I don’t remember it, anyway. But as an 18-year old, I knew that there was a chance it wasn’t safe for him, for us. What if something had happened? There were no cell phones back then. Somehow, I forced that memory from my mind until this week, and cried as I told my husband about the memory – one so painful, that at age 49, I finally shared. That was 31 years ago, and here I am crying from watching a documentary.

And right now, I’m sad. The idea that something could have happened—his life, my Gram’s and mine—could have been changed forever. And who would have known?

So when people want to talk about how kneeling is disrespectful, I think about this country’s history when it was disrespectful to humanity when people couldn’t walk without chains, learn to read or write, dance to the beat of their native music, get legally married, eat where they wanted to eat, own a home, earn fair wage for their labor, try on clothes in a store, walk down a certain street because it was quicker, and couldn’t have their lights on after dark for white supremacy was afraid that they were planning a civil rights meeting. I think about how disrespectful all of that was to humanity. The laws have changed, but attitudes haven’t.

Oppression was so dominant that human beings were called “beasts and monsters.” And here we are in 2019, discussing basic civil rights. But we don’t want to talk about that. Instead, we want to push it under a rug because the past is ugly, and it’s best to leave it be.

Well, we can’t leave it be when we have people on our campus who won’t let it be. They want to celebrate a flag and statue that represent so much more than “their heritage.” There isn’t white heritage. There’s Italian heritage, Irish heritage, English heritage, etc. This southern history, where black women were worked like dogs on the chain-gangs for talking back, or the only employment black women could get after Emancipation was subservient jobs as domestic workers. Where grown men were called boys in public, or even “house boys” when working at sorority homes, or brutally beaten for not stepping off the sidewalk when a white person approached their direction.

If people read history books written with facts and honesty in all its ugliness, maybe the world would be a better place. No one is asking anyone to apologize for what they haven’t done, but how do you move on if you can’t even face it and talk about it? And if people want to talk about southern pride – they should know the facts about southern pride and all that comes with it. It’s that simple. You don’t get to be selective.

And now we have students, of all races and ethnicities, who were afraid—some terrorized—by people coming to our campus on Saturday, Feb. 23, 2019, threatening to wear guns and personally calling out student leaders’ names (a video since removed from social media), who counter-protested their Neo-Confederate demonstration in support of the contextualized Confederate statue on campus.

I want all parents to think about their precious children, going to this campus and wanting them to just get an education and hopefully turn out to be even better human beings than we expect. We want them to understand a world that is much bigger than them, than all of us. We want them to learn how to have conversations and respect differences with people who look different from them. And we all deserve the right to feel safe walking on our campus.

And I thank those brave young Ole Miss basketball players who kneeled, because they were tired of having their campus assaulted with yet another protest that represents hate on a campus where they work hard to dream of a better life, even through sports. Yes, they are benefitting from playing. And they are providing a lot of money through their labor to this university, where for years people had the audacity to wave Confederate flags while they played and represented this institution. Where black students in the band were disgusted while playing Dixie but had to because they had scholarships. What nerve.

The players have a right to kneel.

No athlete has said they kneel to disrespect military service or veterans. And for those who want them to “just shut up and play” and say “the court or field is not a place for politics,” I say sports is the epitome of politics. Let’s call that for what it is, too.

And for those who want it the way it was, that war was lost almost 155 years ago. And like most things in life, change is inevitable. We deal with it and adapt.

It is a heavy burden for us to ask those young people to be the face of saying no to hate when I think university administrators, not just coaches, should be audacious and responsible enough to do it.

Be on the right side of history and human decency.

The silence is deafening. We hear you. Some say they want this university to be what it was – Dixie and Confederate flags. But they want the players to give their physical and emotional labor. That’s interesting you benefit from their labor then oppress them. For people cannot tell others to get over slavery and all the ugliness that comes with systemic oppression and then talk about southern pride. To do so is irresponsible.