Featured

From Segregation to Success: Teacher Uses Past as a Change Agent to Help Underachieving Children

By Maddie Medina

mrmedina@go.olemiss.edu

*Editor’s Note: This story was originally posted on Oxford Stories

Janice Carr explained the slave trade by using one of the murals at the school. Photo by Maddie Medina.

Janice Faye Carr overcame a challenging past filled with segregation and division and now uses it as an agent to build a successful program to help underachieving children.

“I would see the condition that black people were in, and I would say, ‘There must be a better way,’” Carr said.

Carr is the executive director of the Gordon Community and Cultural Center—an organization that turned an old segregated schoolhouse into a renovated, functioning center that hosts summer programs for children who are struggling in school to reach their full potential.

Carr’s life has not always been easy. Growing up in Clay County, Mississippi, she changed schools in the 6th grade, when schools integrated, from segregated South Side Elementary to West Point Junior High School and eventually graduated from West Point High School.

At a time when the state of Mississippi was still showing resistance to the integration of schools, Carr was given a choice of which school to attend through the Freedom of Choice Program where students could attend either white or black schools.

“In the black schools, we would get the books from the white schools, and the books would be torn up, the pages torn out of them, but that’s all that we had to use,” Carr said.

Wanting a new book, she decided to attend the ‘white schools.’ After convincing her father, who was illiterate, to sign her slip to change schools, Carr made the transition.

Carr recalled a vivid day in 1968, following the death of Martin Luther King Jr. “When we came to school the next morning, all the [white] kids were pointing and laughing about it,” Carr said.

After several fights broke out, resulting in the expulsion of black students, Carr was told by her mother to stick it out and stay at the school despite the fact that she was one of the few black kids left.

As one of only three black students left in her class following the expulsions, Carr was neglected by her teacher because of her skin color. “The three of us were always put to the side of the room by ourselves, and the teacher would teach to the white students,” she said.

Carr’s resilient nature was prevalent at a young age. After receiving a report card of all Fs, she returned the next semester and received much higher grades despite being neglected by the teacher. Having received straight As at her old school before integrating, Carr described the situation as traumatic, yet she managed to succeed in this new environment as well.

However, it was not just academic struggles that Carr faced.

“While I was at that junior high school, I never went to the bathroom,” she said. “I was afraid to go to the bathroom.”

Along with the fear she faced at school, Carr vividly described the trauma she faced walking to school with her siblings. At the time, only white kids were allowed to take the bus, and the bus driver would aim for mud puddles to drench the kids who would then have to go to school wet, she said.

Carr faced these challenges at a young age, yet was able to overcome them and went to college at Jackson State University, moved to California and earned her law degree. As she was a self-proclaimed, temporary “visitor in California,” Carr eventually moved back to Mississippi and ended up in Oxford after hearing about the town on the Oprah Winfrey Show.

Blown away by the beauty of Oxford, Carr settled here and came across an abandoned school building in Abbeville. The location of the schoolhouse holds a lot of historical significance, as it was the site of a previously black segregated schoolhouse.

“The Southern states dragged their feet on integration, but [they] tried to placate the federal government, so they started to build schools for black students,” Carr said. “This is one of the first schools they built for black students. It went from 1st to 8th grade.”

Eventually, when the schools in Mississippi were integrated, the students attending the school were bussed to other schools in Lafayette County. This left the school abandoned and in about the same condition when Carr found it almost 40 years later.

“It’s very touching because when she moved back here, she was really concerned about [the schoolhouse] because buildings were just sitting there,” said Ann Delores Herod, one of the original teachers at the school. “It’s part of our history, and to let that building go to waste… Eventually they were going to tear this one down.”

After thinking about it for several years, Carr reached out to friends—some of whom had attended the school when it was still segregated—to put her plans to action.

Together, the group of ladies formed the first board of directors and gathered the community to renovate a 40 year old building to allow for a summer enrichment program.

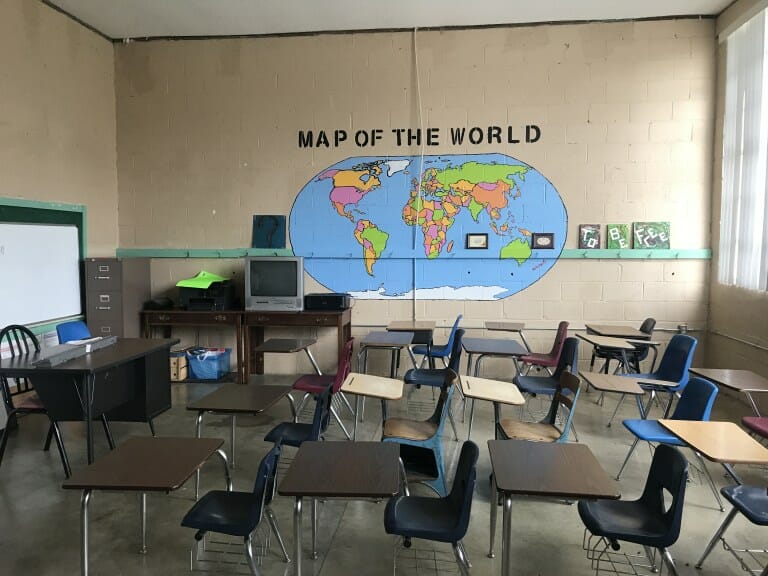

One of the classrooms at the Gordon Community and Cultural Center. Photo by Maddie Medina.

“We had women that were 70 years old climbing and painting,” Herod said.

The 13 students in the first program had no bathrooms, no running water and no air conditioning, but they still made it work, according to Herod.

Carr’s program for underachieving students has been going for five years now and includes classes in language arts, math, cultural enrichment, spiritual enrichment and health education, eventually adding financial literacy for youth.

“It’s more than just academics,” Herod said.

The school brings in speakers for the children, as well as taking them on field trips to local sites, such as the Emmett Till Museum.

The program also encourages children to look towards their future, with several banners from Historically Black Universities lining the halls. It also reminds students of the history of the building, with images of graduates from the original segregated school hung in the entrance.

In next year’s program, Carr plans to add Swahili. They are also adding a program to help adults with any skills that can be used to build a house, such as carpentry, plumbing and other skills.

As for the types of students the program hopes to target in the upcoming years: “We want students that are struggling in school because they can get more one on one and be ready for the school year,” Carr said.

Having lived a childhood typical of the segregated American South, Carr overcame her challenges and created a positive change that for many people would have been too big a challenge to overcome.

“You remember the past, but you live in the present, and you work towards the future,” she said, “so you don’t live in the past, but you don’t forget it.”