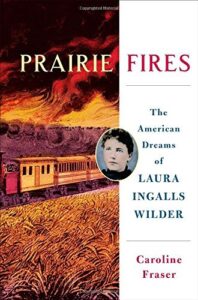

“Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder,” by Caroline Fraser. Picador Books, 626 pp. $22.00 (paperback).

With a reader’s love for the “Little House” books of Laura Ingalls Wilder, a critic’s knowledge of the historical forces boiling like prairie thunderstorms in the background of those stories, and a shrewd human understanding of the family dynamics that shaped how Wilder penned her novels, Caroline Fraser has written a brilliant biography of the barefoot farm girl who earned five Newbery Medal nominations in seven years and taught generations of schoolchildren about life on the American frontier.

“Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder,” appears in paperback now—recognized with this year’s Pulitzer Prize for biography and acclaim from the New York Times Book Review and the National Book Critics Circle. It joins a distinguished company: 75 years after Wilder’s final novel appeared, all of her books remain in print.

Fraser points out that the “Little House” books are novels, not memoirs. Wilder insisted that her stories were true, and they were: she remembered vividly how happy her family had been when Pa dug a well and how trying it had been to teach in a country schoolroom. She wanted not to remember how her father had struggled financially and how her strong young husband had been crippled by a stroke. Writing fiction, she could elide parts of the whole truth.

“The misfortunes of Charles Ingalls’ failed crops and unpaid debts [became] an orderly westward progression to homestead and town,” Fraser comments. Wilder’s novels, which ended with “These Happy Golden Years,” supplied “her last opportunity to spend time with parents long gone, her last word on a marriage that began with such joy and promise.”

Wilder’s novels have their dark pages. There are evictions, blizzards, wildfires, plagues of locusts and blackbirds, and allusions to the “Minnesota massacre,” something Ma puts off explaining. The Ingalls family handles these calamities as part of frontier life. Looking beyond the horizons of the novels, Fraser draws broader connections—to depressions, Wall Street panics, the Dakota War, and the reckless plowing that would create the Dust Bowl. She locates Wilder, along with Hamlin Garland, Willa Cather, Ole Rølvaag, and L. Frank Baum, among those writers who accept so wholeheartedly the myth of the American frontier and the self-reliant frontiersman that they fail to recognize that the land alone cannot support the settler.

Fraser dispels the claims that the “Little House” books were ghostwritten by Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, a high-strung globe-trotting journalist who exchanged letters with Ayn Rand. By pointing to Rose’s mediocre magazine serial “Free Land,” which made ham-handed use of the same family stories that Wilder would draw on, Fraser shows how badly Rose could write when she worked solo. But if Rose lacked her mother’s gifts as a novelist, she was more experienced; a “secret editor,” she offered guidance that her mother closely followed.

Wilder’s strength and endurance, Fraser finds, lies in the simple eloquence and humanity with which she told her family’s story and to which numberless readers have responded. As Fraser concludes:

“The truth about settlement, about homesteading, about farming is there, if we look for it—embedded in the novels’ conflicted, nostalgic portrayal of transient joys and satisfactions, their astonishing feats of survival and jarring acts of dispossession, their deep yearning for security. Anyone who would ask where we came from, and why, must reckon with them.”

Allen Boyer is the Book Editor of HottyToddy.com. A different version of this review was previously published in the Phi Beta Kappa Key Reporter.