Featured

Allen Boyer: Review of “Mississippi” by James A. Autry

Editor’s Note: James Autry, author of “Mississippi,” will meet students, faculty, and the public on Thursday, October 11, at 2 p.m. in the Overby Center lobby.

“Mississippi” by James A. Autry is the collection of 77 poems.

In “Mississippi,” James Autry – country kid, airman, editor, businessman – has collected 77 moving poems.

Autry, a poet featured in broadcasts by Bill Moyers and Garrison Keillor, writes often of country life – hunting, fishing, plowing, planting, going to the store and visiting the outhouse. Church on Sunday with lunch on the grounds. Teenage kids in battered cars. In other poems, travelers study snapshots of life in airport corridors, and fighter pilots dazedly try to figure which of their squadronmates has crashed. Elderly patients and visitors struggle in the glare of hospital lights.

Autry was born in 1933. He grew up in Benton County, between Ashland and Hickory Flat. His father and grandfather were Baptist preachers. He made his career, steadily and very successfully, as a magazine editor.

Autry began writing poetry in 1977. He heard James Dickey reading one evening: “It was so powerful, so full of what I wanted to create that I returned to my hotel and scribbled seven short poems before the night was over. They were terrible but represented a change of form and, more important, a change in my thinking.”

Autry’s family members play checkers. Photo by Lola Mae Autry.

The form is different, but Autry shows a feature-writer’s skill in the capsule biographies that he sketches – of country preachers, hunters, matriarchs. And of Uncle Vee, a man to be remembered.

“Uncle Vee is the last one now

and I wonder if he’s the only man in Mississippi

who still lives in a house he built

of raw lumber sixty years ago

who plowed a mule in red clay,

over and around hills,

not a flat spot on the place . . .

who ate pork and greens and cornbread,

and drank gallons of buttermilk,

and got bigger and bigger

but at eighty-six was still hungry every day . . . .

The scenes are nostalgic, and the tone is humorous – but in the end there is nothing sentimental here. The poem is titled “Your Uncle Vee Had A Massive Stroke Last Night”; its montage of memories is framed in black.

Or take the story of “Mister Mac,” the insurance salesman who was the only Republican in the county.

“Mister Mac thought they they admired his spunk

despite how they treated him . . .

but when he died and his cousin sobbed

all through the service

and told me, ‘Jimmy there’s not a dry eye

in this town today,’

the preacher had to ask the people

to bunch up in the front

so it would look like a crowd.”

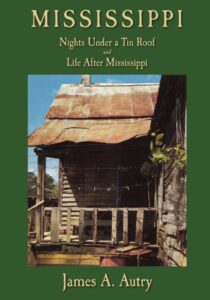

“Mississippi” collects two earlier books of poetry, “Nights Under A Tin Roof” (1983) and “Life After Mississippi” (1989).

To the original volume of “Life After Mississippi,” Willie Morris (who also knew his way around the magazine world) contributed an introduction. Perceptively, Morris noted: “What Autry is writing about, again and again, is home.” Morris also identified a crucial line in one of Autry’s poems: “Life is largely a matter of paying attention.”

Many poems in “Life After Mississippi” report scenes from Autry’s later career, when he flew fighter planes for the Air Force, edited Better Homes and Gardens Magazine, and served as a senior executive with Meredith Group, a media firm in the Fortune 500. Here, from the end of the 1980s, is his take on American culture.

“There’s a line I want to use,

see?

in a poem I want to write,

okay? . . . .

Hey look, seriously, the line is

(are you ready for this?)

‘living lives of boisterous desperation.’

Lives of boisterous desperation.

How about that?

Not quiet desperation, like the other guy wrote

about another time and another place,

But boisterous desperation.

Get it?

Get it?

Sure you do.”

Autry can talk the language of business pitchmen as well as the dialect of the Southern backcountry.

Autry family members seine for minnows. Photo by Lola Mae Autry.

Autry writes free verse, or nearly free: there is a beat to his phrases and the length of the lines is paced to match the narrative. Most poems might easily be turned into short prose essays, but they are clearly poetry; the images have been crisply focused, the writing tightened.

Robert Frost considered that writing free verse was like playing tennis without a net – and no American in the last century wrote as many fine poems as Frost – but some of Autry’s Deep South country scenes will you make think of Frost’s New England country scenes. Autry shares with Frost a sober, somber awareness of mortality and a remarkably vital talent for sketching scenes from life.

Allen Boyer is the Book Editor of HottyToddy.com.