Editor’s Note: Robin S. Lattimore read and signed copies of “Southern Splendor” Sept. 28 at Off-Square Books.

“Southern Splendor” looks like a coffee-table book about mansions of the Old South; except that it isn’t. Mixed with its collection of stunning color photos of elegant houses and jewel-like architectural details are grainy, battered black-and-white images of homes that are down at heels, covered with poison ivy, even ruined – the houses in question before they were restored.

In most of the mansion biographies that accompany the photos, the antebellum past is often the briefest part of the essay. More space goes to the vicissitudes that these houses have endured. They have been burned, flooded, converted to tobacco barns, bombarded by Union gunboats, made part of Army Air Corps bombing ranges, ripped apart by tornadoes, sawed into pieces by feuding heirs, disassembled and warehoused by aficionados – and allowed to decay, and abandoned. Some descend along a line of owners in a single family.

Others have changed hands 17 times in 90 years. Their stories are of calamity and chance and whim. Rattle and Snap Plantation, southeast of Nashville, was won and lost on the roll of a handful of dried beans, and would have been burned had not a Union general learned that its secessionist owner was a fellow Mason.

This book tells the story of 48 Southern homes, in an arc stretching from Virginia to Louisiana. (No homes from Florida are featured, and the book stops at the Mississippi – three Louisiana sugar barons’ homes on the west bank of the great river are included, including Nottoway, the largest plantation house in the South.) Not all are white-columned neoclassical residences; one is a solid-looking brick townhome in Richmond, the presidential residence of Jefferson Davis. The oldest mansion is Drayton Hall, in South Carolina, completed in 1742, where Lord Cornwallis once slept. Most of the others were built in the early decades of the nineteenth century, by owners who prospered as cotton and slave labor garnered them boom-and-bust fortunes.

Each essay provides a study from a different angle, of a different problem, of the work of historical restoration. In Virginia, the long shadows of George Washington, Robert E. Lee, and Thomas Jefferson continue to complicate the preservation of Arlington House and Monticello. The mansion at Carnton, outside Franklin, Tennessee, sits in the middle of a Civil War cemetery, thousands of Confederate burials from the Battle of Franklin. (“This is where the Old South died,” its restorers commented.) Sometimes proprietors who cannot care for a place demand to live on there as life tenants. Some restorers face the daunting challenge of restoring a house to match a record provided by detailed plans, inventories, and photographs; others must discover what a house looked like as they go. Money poses a perennial, ubiquitous difficulty.

In Mississippi, “Southern Splendor” profiles four homes. One is Ellicott Hill, in Natchez, a handsome Caribbean building. Another is Hollywood, in Bolivar County, battered over the years by floods and storms, now called the Baby Doll House after a Tennessee Williams movie shot there in 1955. The elegant rotunda of Waverly Plantation, midway between West Point and Columbus, where bats and beehives had to be routed out of attics, features twin staircases with walnut spindles, all refinished by hand. And of course there is Beauvoir, Jefferson Davis’ last home, the most recent chapter of whose story is the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina.

“In 1861 [the authors write] approximately 46,275 plantation homes existed across the South. . . . Current estimates suggest that fewer than 6,000 antebellum plantation homes still survive in the entire South.”

Plantations were for the Old South what factories were in other places’ company towns. In the modern South, plantation homes serve as homes, garden club showplaces, tourist attractions, and wedding halls. Some host black family reunions. Others are museums – some focused on planter families and Confederate leaders, others on the lives of the slaves who built the mansions and the society around them.

Those mansions that survive have done so – the stories in this book suggest – not because they were monuments to the past, but because, over generations, they met the needs of communities. And “Southern Splendor” will remind readers that this history is still evolving.

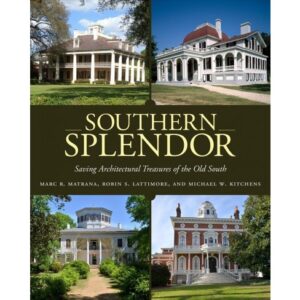

“Southern Splendor: Saving Architectural Treasures of the Old South.” By Marc R. Matrana, Robin S. Lattimore, and Michael W. Kitchens. University Press of Mississippi. 391 pages. $40.00.

Allen Boyer is Book Editor for HottyToddy.com.