Arts & Entertainment

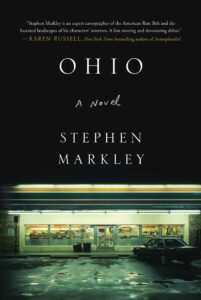

Allen Boyer: Review of “Ohio” by Stephen Markley

Editor’s Note: Stephen Markley will read and sign copies of his book “Ohio” on Wednesday, September 19, at 5 p.m., at Off-Square Books.

“I went back to Ohio / but my city was gone.” A rock ‘n’ roll amazon sang those lines, and a right-wing radio talk show host made them his theme song. They might be the epigraph for Stephen Markley’s powerful first novel “Ohio,” which covers the same Rust Bowl terrain and the similar hard-bitten ironies.

“Ohio” is Stephen Markley’s first novel.

“Ohio” is set east of Columbus and south of Cleveland, in the town of New Canaan (amid a swathe of real-life towns with equally buoyant names, New Philadelphia and New Concord). New Canaan has been battered by factory closures, subprime mortgage evictions, and opioids. Family farms have been bought up by agribusiness. Young people leave, or settle into what they find, both in jobs and in relationships.

Danny Eaton, a quiet kid who reads history, deployed three times with the 101st Airborne and came home with an acrylic right eye. Lisa Han was bright and rebellious; she vanished and apparently never looked back.

Ben Harrington became a singer-songwriter; he overdosed. Rick Brinklan came home in a coffin from Iraq. Kaylyn Lynn, a prom-night beauty, got as far away as Toledo. She started with Percoset, moved on to Oxycontin and meth, finally shot heroin. She was Rick’s high-school girlfriend. At his funeral, she was too high to speak.

As the book opens, Bill Ashcraft, an unmoored chaser of radical causes, comes home strung out on meth and LSD and carrying a tightly-wrapped parcel – contents unknown – taped to the small of his back. A different road brings to town Stacey Morrow, once “the hottest church-camp girl in the school,” now a lesbian writing her dissertation.

The threadbare state of the republic can be judged by where Markley’s characters spend their time: Walmarts, bars, all-night diners, rehab wards, and retirement homes. (When the largest local employer is the hospital, is it surprising that the most common crimes involve prescription drugs?)

Author Stephen Markley.

These days are not the only dark chapter in New Canaan’s history. High school students remember how women of the Shawnee tribe singled out captive enemy warriors for fiery deaths. People talk about The Murder That Never Was, a local urban legend of a killing that was swept under the carpet. When a covered-up crime becomes town gossip, something remains unsettled. The Murder That Never Was will cast long shadows.

This novel is a cautionary tale about teenagers with time on their hands – Markley, himself a native of Ohio, knows well how much adolescent sexuality can be packed into classrooms and church groups. It is a coming-of-age tale about adults putting high school behind them: by meeting elders on equal terms, by getting off drugs to take care of children, by unleashing a sudden ferocious strength when people need it. Those qualities, “Ohio” suggests, are virtues on which we still can draw.

“Once over the hump of Youngstown,” Markley writes of a character driving home, “it was nothing but the rippling green spears of cornstalks, the trembling soy leaves awaiting the sweatless industrial harvest.”

“The mile markers fell and the telephone poles bled tar. The sky went from a deep orange to a bruise of purple and blue, the clouds carved by shafts of biblical sunlight – here lighting a patch of cud-stuffed cows, there illuminating a fallen bard with Ohio’s bicentennial logo flaking paint . . . . Even if you’ve traveled the world and seen better sunsets, better dawns, better storms – when you get that remembered glimpse of the fields and forests and rises and rivers of your home meeting the horizon, your jaw will tighten.”

“Ohio” is ambitious and sweeping and masterfully written. Beneath the flashbacks, the plotting is tight, zeroed in on one long evening in the summer of 2013. The stories that intersect that night stretch out from New Canaan to Afghanistan and Croatia and Cambodia. (A taut epilogue nails down the sharp rhymes between Ohio and those war-torn places.) The dialogue is crisp. The plot twists can be unexpected but are never improbable. There are dozens of characters, some of them major, all of them memorable.

This is a book about war and peace and hard times, families and hometowns and missed connections. Modern writers seldom dream this grandly. As if a literary gene had skipped a generation, “Ohio” has the heft of the great big-boned American novels: “From Here to Eternity,” “The Naked and the Dead,” “The Grapes of Wrath,” and, farther back, Thomas Wolfe and “You Can’t Go Home Again.”

“Ohio” is weighty, but most of this novel is muscle and nerve. The book will seem long until you realize that you want to keep reading it.

Allen Boyer is Book Editor for HottyToddy.com.