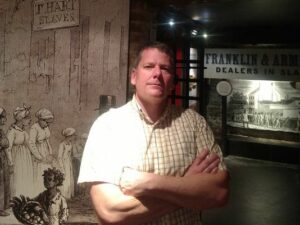

Working from records hidden in plain sight, Bill Carey has written a perceptive, provocative book. Searching through early Tennessee newspapers, Carey has located more than a thousand advertisements for runaway slaves, notices that ran alongside ads offering slaves for sale or seeking slave labor for projects. “Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls” casts new light on the slave culture of antebellum Tennessee – and, beyond that, offers a vivid group portrait of people who bucked that system and struck out on their own.

Carey founded Tennessee History for Kids, a non-profit organization that provides resources for public schools. Before he turned to history, Carey was a reporter, and he shrewdly points out what lies behind the advertisements. “A runaway slave ad was typically 10-30 lines long, usually enough room for 100 to 300 words,” he notes.B

The style and format of the ads say more. As early as the 1830’s, the ads were routinely marked with artwork, the picture of a runaway slave. “The ubiquitous silhouette of a slave heading down the road with his meager possessions tied to a stick slung over his shoulder appears to have been one of the very first pieces of design work created in the offices of newspapers across the state.”

Carey translates the language of the ads. A “likely Negro” was one who seemed strong and capable. “Fancy girls” were light-skinned, pretty young women, usually of mixed race. They might end up as planters’ mistresses, in New Orleans bordellos, or barmaids on riverboats. “Fancy boys” were handsome youths favored for doormen or body-servants.

“Coffles” were columns of slaves marched to market in long lines, chained together. Tennessee law forbade “importing” slaves, but the statute was riddled with loopholes. The state’s most fearsome slave trader, Nathan Bedford Forrest of Memphis, openly let the Memphis Appeal describe seven African slaves he was offering, “direct from Congo.” This was in April 1859, fifty years after bringing slaves directly from Africa had been banned. Forrest feared no man and clearly he did not fear the law.

Slaveholders might write very little in their advertisements (“a likely Negro girl, aged fifteen or sixteen”) or provide a full capsule portrait. In 1840, William Massengill described pithily a young man who had run off from his mountain farm outside Dandridge:

“GEORGE, aged about 28 years, of a tawny color, six feet high, straight and handsomely built, inclining to Roman nose, assuming consequential airs when spoke to; by trade a brick-layer, plasterer, and painter – has pretensions as a barber.”

Margaret was 21 when she ran off from Shelby County in 1846. She was “almost entirely white,” with blue eyes, and spoke Cherokee and French. Margaret came from Arkansas; three months in Memphis had been enough for her. What was her story beforehand, and what did she do for the rest of her life?

Some of the escaping slaves were blacksmiths. Others had been shoemakers, carpenters, cotton-gin operators, preachers, conjurors, and stable-hands at the Female Academy of Nashville. They tried to get aboard steamboats, just as Frederic Douglass would flee to freedom by boarding a train for Philadelphia. Only rarely did escapees head north. Much more often, they headed for their families or former homes (or so slaveholders anticipated). One escapee was even thought to be making his way to South Alabama.

Many looked down when spoken to, or stammered – they had learned to do that. Others talked to white men face to face. Some tried to escape more than once, or were so determined that that they made their escape while still wearing irons. (Did they count on finding a slave blacksmith to strike off their fetters?)

In a slave society, governments used slave labor. The city of Nashville bought slaves to build its first waterworks, and a slave died quarrying limestone for the Tennessee State Capitol. Banks offered credit to slave traders and loaned money to slaveholders who used slaves as collateral. “Tennessee’s antebellum banks would have viewed the emancipation of slaves with the same enthusiasm [with which] a modern-day bank would view a stock market crash,” Carey concludes.

Nor was the press innocent or independent. Many ads ended, “Apply to the printer.” Carey spells out what this entailed:

“The phrase ‘apply to the printer’ indicates that newspapers provided an additional service beyond just printing these ads. A person selling slaves could hide his or her identity from the public by using this clause, which required prospective buyers or sellers to come to the newspaper office to find out more. . . . Regardless of the reason, almost every newspaper in Tennessee regularly acted as an agent in the slave trade.”

An appendix summarizes more than 900 advertisements purchased by Tennessee slaveholders seeking runaways. The first ad ran in October 1792, the last ad in late June 1864. This material is to be prized. Slave masters wrote the advertisements – but for hundreds of slaves, men and women who had the ambition that makes history, the runaway ads supply names, homes, birth years, occupations, and abilities. Such data can be traced into census records. And as for the runaways’ descriptions, those catalogues of skin tone and scars and mannerisms – some of those descriptions may yet be recognized in daguerreotypes.

Allen Boyer is the Book Editor of HottyToddy.com. Born in Memphis, he studied in Nashville and has taught law in Knoxville.