Arts & Entertainment

Allen Boyer: "Warlight" by Michael Ondaatje

Allen Boyer

Hottytoddy.com Book Editor

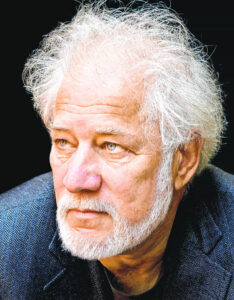

Michael Ondaatje is the author of “Warlight”. Photo courtesy of the author.

In “Warlight,” by Michael Ondaatje, a pretty decent spy story has fallen into the hands of a self-conscious post-modern novelist, and that’s not good. The novel runs from about 1930 to about 1960. Most of its characters are British men and women—spies and spymasters who spent the war defending their nation, and devoted the years afterward to keeping silent about their wartime service.

Unfortunately, “Warlight” broods portentously on what wasn’t said, or what cannot be known, rather than imagining what that service meant. The book’s first sentence signals the problem. “In 1945,” Ondaatje writes, “our parents went away and left us in the care of two men who may have been criminals.” That sets up a promising beginning, but the tone is full of doubt and that sentence is slack.

The narrator, Nathaniel, tells a coming-of-age story from postwar London. The two with whom he and his sister are left (he prefers their nicknames) are the Moth and the Pimlico Darter. The Moth and the Darter have dubious friends and traffic by night in racetrack greyhounds. Nathaniel slowly reconstructs the career of his mother, Rose. Rose is an upper-class beauty who works with radio intelligence during the war. Her clandestine service in Italy, caught between Mussolini’s Fascists and Tito’s Communists, leaves her with a painfully scarred forearm and the lingering hatred of a doomed company of partisans.

Nathaniel hesitates to reach conclusions – even to give descriptions. (“We never know more than the surface of any relationship after a certain stage.” “Most of the time I found only the names of cities stamped blurrily in her passport, along with fictional names she’d used . . . so I gave up being certain.”) Ondaatje seems to believe that being vague is the same thing as being subtle. Sadly, this book is always vague and never subtle.

The writing is full of lofty pronouncements. (“The lost sequence in a life, they say, is the thing that we always seek out.” “Do we eventually become what we are meant to be?”)

The narrative winds through an obstacle course of symbols, metaphors, and allusions. A character who makes the improbable rise from country thatcher’s boy to intelligence mandarin is named, equally improbably, Marsh Felon. His ambition is signaled by his fondness for scaling the battlements and finials of Cambridge college buildings.

The troubled relationship between Rose and Nathaniel is reflected by their chess-playing, culminating in an overlong discussion of one memorable chess game. This was the 1858 match in which the New Orleans prodigy Paul Morphy defeated two celebrated European players, the Duke of Brunswick and the Comte de Vauvenargues, playing in a box at the Paris opera while “Norma” was being sung below. Ondaatje pursues this tangent across five pages – perhaps forgivably. For Paul Morphy trouncing two fops while passionately trying to listen to the magnificent opera being sung at his back is the most vivid scene in this book.

John Le Carré, who had a conman for a father and an early career as a spy, could have told this story crisply. (Le Carré has written better books about both milieus – read “A Perfect Spy” or his memoir “The Pigeon Tunnel.”) So could Sir John Mortimer, who could flawlessly plot a story and brilliantly sketch a character, and who was funnier than Ondaatje will ever dare to be. (Horace Rumpole probably defended some of the petty villains to whom the Darter delivered greyhounds.)

Boldness and sharpened wits and appreciation of detail – those qualities make the crook, the secret agent, or the novelist. Those qualities are lacking here.