Editor’s Note: Charles Frazier will read and sign copies of “Varina” at 5 p.m. Wednesday, April 25, at Off Square Books. Recently, he spoke with HottyToddy Book Editor Allen Boyer.

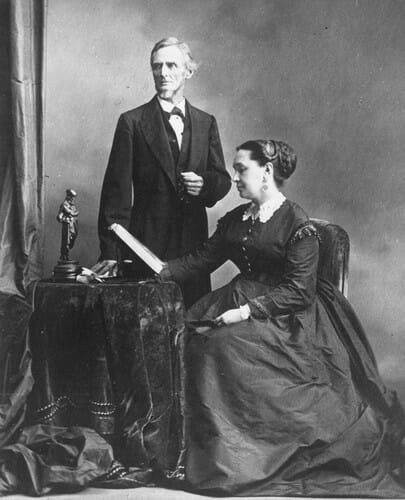

“Varina,” a new novel by Charles Frazier, explores the life of Varina Howell Davis, wife of Confederate States of America president Jefferson Davis. V, as Frazier calls his heroine, was a woman who made her own way across the most turbulent years in American history.

The 19th century has been Frazier’s domain. His first novel, “Cold Mountain,” was a monumental Civil War tale and won the National Book Award. He followed that with “Thirteen Moons,” a century-spanning novel set in the Cherokee country of the Blue Ridge Mountains. After visiting the 1960s in his third novel, “Nightwoods,” Frazer has returned to earlier times.

“Varina” opens in 1906, in Saratoga Springs, New York, in a grand establishment that is part resort hotel, part sanitarium. It ranges across raw antebellum Mississippi, where plantations were being hacked out of the forests and canebrakes; Washington, D.C. before the Civil War and Richmond during the Civil War; and as far west as Memphis and as far east as the Black Forest spas of Germany—places where Varina Davis and her husband wandered (each on their own, mostly) during the long decades after the war.

In the novel, Jefferson Davis is less a character than a presence. Varina was a faithful helpmeet to Jeff, but they routinely lived apart. Before the Civil War, Jeff spent time in the army and in Congress, leaving her to run his plantation south of Vicksburg. After the Civil War, things were little better. One time, Varina was in London, Frazier points out, and expected Jeff to meet her there. Instead, as soon as he landed in Liverpool, he wrote that he was going on a tour of Scotland.

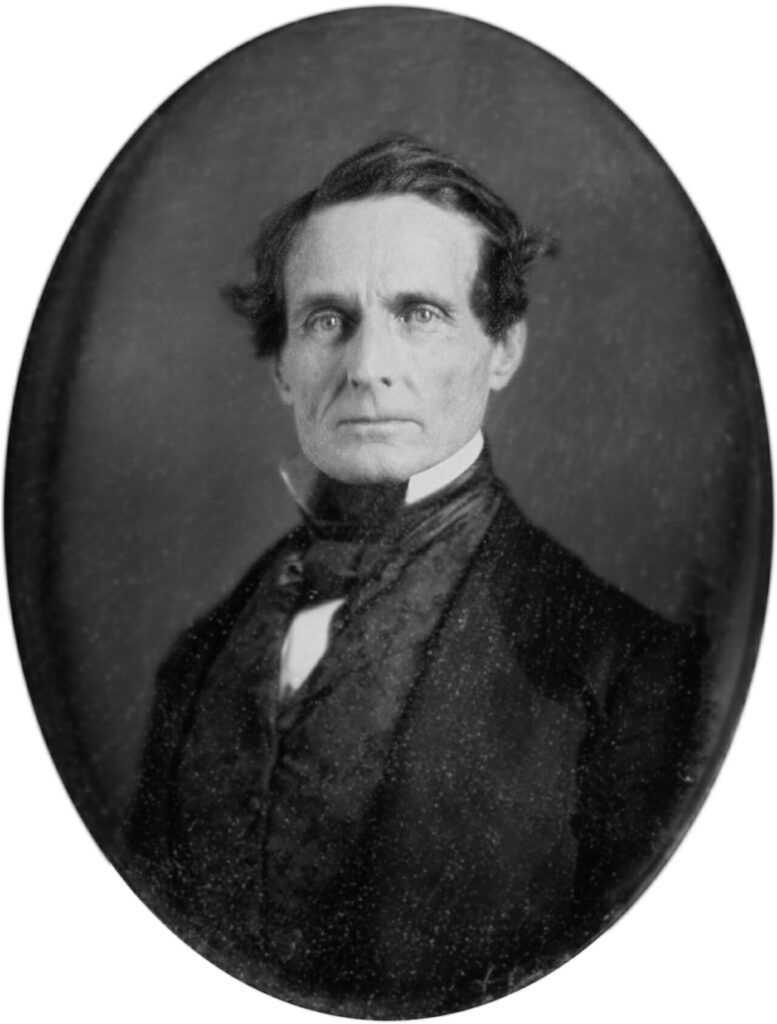

While doing research for “Varina,” Frazier discovered that an immense number of people who knew Jefferson Davis disliked the man: “He was such a distant person to so many people,” Frazier said. “Sam Houston said he was cold as a lizard and as ambitious as Lucifer. I didn’t like him either. He had temper and pride and always went around with this quivering anger.”

Only in the closing chapters, when Davis has retired to Beauvoir on the Gulf Coast, was Frazier comfortable with Davis. “He was a ghostly presence then,” Frazier said. “That’s how I wanted to remember him.”

Frazier found that Varina Davis was tall for a woman of her era, perhaps 5’7”—tall enough to draw ridicule. During the war, “Richmond society ladies said that she was ‘too Western,’ which means ‘too frontier,’” Frazier noted. “She was not as refined as they wanted her to be.”

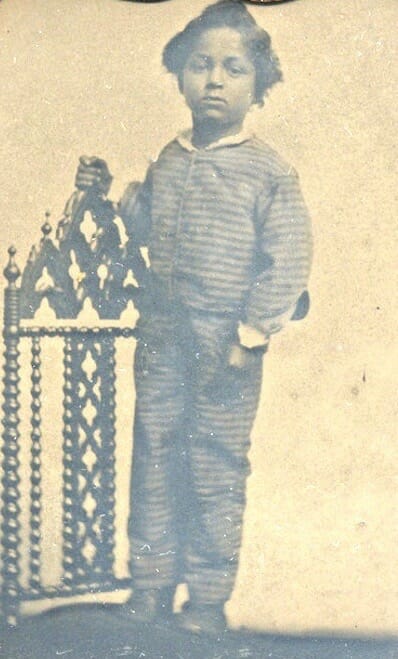

The matrons of Richmond also whispered about Varina’s dark hair and olive complexion. They said she had Indian or Negro blood. When she took into her household a small mixed-race boy, Jimmie Limber, rescuing him from a beating on the street, the rumor spread that Jimmie was actually her own son—or her husband’s child by a black woman.

Jimmie Limber is a figure from history. Frazier found a daguerreotype portrait of the little boy, apparently taken in the same studio in which portraits of the Davis family children were made during the same war years. “He’s all dressed up and standing beside the same ornate chair,” Frazier observed. “People thought I was making up that story, about a little black boy in the home of the president of the Confederacy. I wrote about him for six months and wondered what happened to that little boy. But the trail runs cold.” (Ironically, the trail runs cold in Boston, where Union officers had placed Jimmie in school.)

When he writes, Frazier said he does not read contemporary fiction. “I’m in the world I’m in, for that period. When I was writing about Varina, I could find a lot of books that she or Jeff read. I read those to immerse myself in that period.” He found that Varina Davis read “a great deal of junk fiction and serious historical works.”

Particularly interesting was one volume: “Either she or Jeff checked out a copy of De Quincey’s ‘Confessions of an English Opium-Eater’ and kept it for several weeks,” Frazier said. In the novel, talking to Oscar Wilde (who actually called at Beauvoir), Varina remarks that opium “is a fascinating substance. Doctors have been shoving it at me since I was thirteen for everything from monthly melancholy to childbirth … They see it as the cure-all for excitable women.”

Varina’s close friend was the diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, another politician’s wife, a fellow bluestocking, and a long-term user of opiates. At the end of the war, Varina and Mary meet while fleeing South. Mixing morphine into red wine, they talk late into the night. The scene is more Ann Beatty than Shelby Foote, but then, often the strangest parts of a history are the truest.

After the war, Varina Davis supported herself. She finished her husband’s autobiography and moved to New York City, where she wrote a column for the New York World. “She stayed for months at the Gerard Hotel, just north of Times Square,” Frazier noted. “The street level has changed, but the building is still there, and you can see the old façade if you look up.”

In the novel, Varina often speaks in her own voice. Remarks that she makes in conversation, or scribbles in the margin of her books, are comments that she made in life, “repurposed” by Frazier from letters that she wrote or reported in conversations by Mary Chesnut.

Frazier found a late-in-life interview given by Varina, in which the reviewer marveled at how up-to-date her reading was. One book she might have been reading then, Frazier imagines, was Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth.” In “The House of Mirth,” Lily Bart, a beautiful and accomplished young lady, falls from the heights of society, has to earn her living, becomes addicted to chloral hydrate, and ultimately dies from an overdose. Better than most, the novel suggests, Varina might have understood how tragedy is a stealthy matter:

“She talked awhile, developing an argument that they—she and Jeff and the country at large—had made bad choices one by one, spaced out over time so that they felt individual. But actually they accumulated. Choices of convenience and conviction, choices coincident with the people they lived among, following the general culture and the overriding matter of economics, money and its distribution, fair or not…

“And then one morning the world resembles the wake of Noah’s flood, stretching unrecognizable to the horizon, and you wonder how you got there. One thing for sure, it wasn’t from a bad throw of the dice or runes or an unfavorable turn of cards. Not luck or chance.”

In the novel, Frazier imagines Jimmie Limber seeking out Varina long after the war. Forty years later, he is known as James Blake, and he is a schoolteacher. He raises questions that will trouble her, just as they have long haunted him (“Did you ever own me?”).

By raising those issues, James Blake sets the novel in motion. He also closes the novel, silently following Varina’s funeral cortege as it travels from New York City to Richmond. What he ponders may speak to what Varina sensed about her husband, as well as what he feels at this parting: “He wonders how it is possible to love someone and still want to throw down every remnant of the order they lived by.”

Varina can never quite break free of the social order in which she lived. That does not mean she was blind to its injustices. Frazier reflects: “Part of what interests me about Varina is that she is not a culture hero, someone who can rise above the values of her time and place. I am very interested in her, however, as someone who continues to evolve in her values and her thinking. I know lots of people in the sixties and seventies who become entrenched or frozen. She was still reading books, thinking and evaluating.”

Frazier thinks well of a sardonic comment by a Latin American writer, Eduardo Galeano: “History never really says goodbye; history says, see you later.” Frazier adds: “I thought I was done with the Civil War. As the last four years have shown, that was not so. The church shooting in Charleston and the flag controversies have shaped my thinking about this book. It’s like the armature inside a sculpture—the Civil War and the aftermath of the Civil War and the issues of the Civil War are part of the structure of this century.”

When he completes a book, Frazier takes time off from writing. This time, “unusually,” his plans are different. He has two projects afoot; each currently runs to about ten thousand words. Both still deal with history, and each focuses on eras a few decades in the past. “I think I will leave the 19th century alone for a while,” he said.

Allen Boyer is the Book Editor of HottyToddy.com. He is the author of “Rocky Boyer’s War: An Unvarnished History of the Air Blitz That Won the War in the Southwest Pacific.”