Editor’s Note: Ellen B. Meacham will read and sign copies of “Delta Epiphany” at 5 p.m. Wednesday, April 18, at Off Square Books.

Editor’s Note: Ellen B. Meacham will read and sign copies of “Delta Epiphany” at 5 p.m. Wednesday, April 18, at Off Square Books.

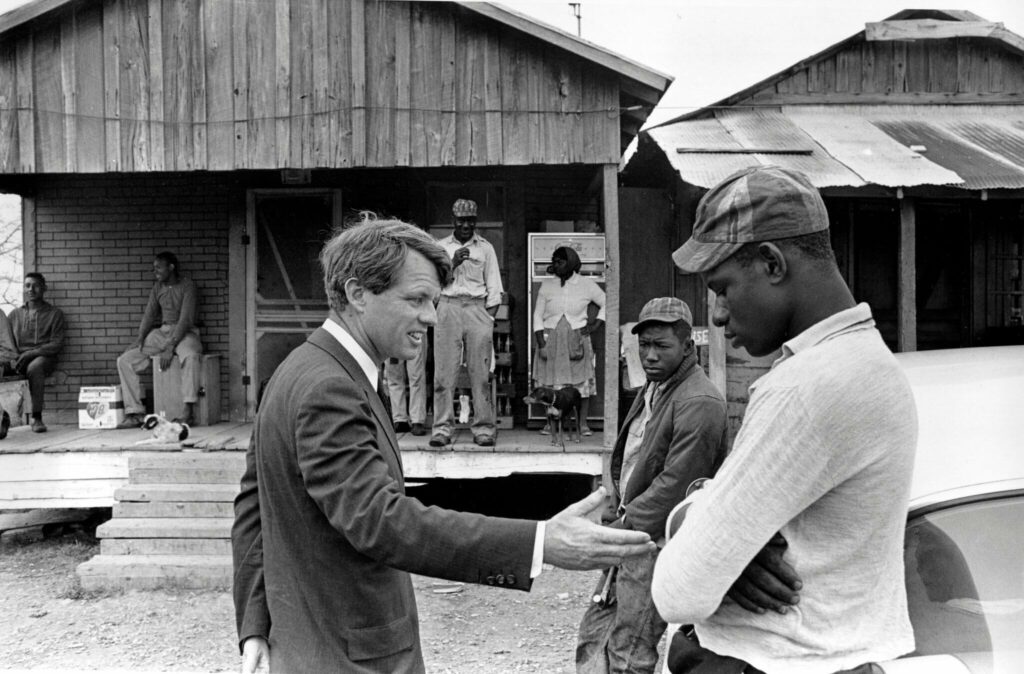

In April 1967, Robert F. Kennedy spent a day driving through the Mississippi Delta. The trip began in Greenville, paused in Cleveland, and ended in Clarksdale – a journey of seventy-odd miles, charged with those ironies that make history. Kennedy was on a fact-finding trip for the Senate Subcommittee on Employment, Manpower, and Poverty, but the journey’s impact was emotional. With Kennedy’s trip as her focal point, Ellen Meacham, a veteran reporter who teaches in the journalism school at Ole Miss, has written a perceptive history of Mississippi in the early 1960s.

For years already, Professor Meacham points out, Bobby Kennedy had involved himself with Mississippi. His career in Washington had meant dealing with crafty old-school segregationists like Senator James O. Eastland. In the spring of 1962, Kennedy had rescued civil rights activist Aaron Henry from police custody; in the fall of 1962, he failed to negotiate the peaceful enrollment of James Meredith at Ole Miss. In the summer of 1963, Kennedy obtained burial at Arlington National Cemetery, with full military honors, for Medgar Evers. Kennedy fought segregation, but he his forceful, cheerful manner was one to which many white Mississippians responded. In 1966, Kennedy visited Ole Miss. An eager crowd turned out to see him, shaking the new Rebel Coliseum with standing ovations.

By the early 1960s, the black communities of the Delta had been battered by a perfect storm of historical forces. Modern herbicides reduced the need for labor (cotton no longer needed to be chopped). Minimum wage laws raised the cost of labor, giving landowners reason to invest in tractors and cotton-pickers, rather than paying farmhands. As a welfare reform, rather than receiving gratis surplus farm commodities (cheese, peanut butter, flour, cornmeal) the poor were now urged to buy food stamps.

In early April 1967, at the Heidelberg Hotel in Jackson, Kennedy’s subcommittee held hearings on allegations that the Head Start program in Mississippi was misusing federal funds. (Senator John Stennis testified in support of the allegations; contrary testimony came from a young civil rights attorney, Marian Wright, who would marry Kennedy’s aide Peter Edelman.) The next morning, after meeting Millsaps College students, addressing Tougaloo College students, and being fêted at a cocktail party hosted by Pat Derian, Kennedy flew to Greenville and began the drive. (Three other senators had presided at the hearings in Jackson; only Joseph Clark, from Pennsylvania, was part of the ten-car entourage.)

As well as a knowing study of Mississippi history, Meacham provides a succinct biography of RFK. Once a crusading, ruthless Attorney General, Kennedy had been shaken by John Kennedy’s assassination. Before he returned to politics, as Senator from New York, he read tragedies, the Bible, and Shakespeare, and he treasured one JFK memento: notes of his brother’s last Cabinet meeting, in which “poverty” was scrawled and circled six times.

The first stop, outside of Greenville, was at Freedom City, a struggling but hopeful cooperative farm. On the East Side of Cleveland, the poverty was worse. At a house that had running water but no toilet, Kennedy handed out fifty-cent pieces (a campaigner’s touch; the coins were Kennedy half-dollars) to the older children. A younger child remained: “At twenty months old, David White was small for his age and wore only a filthy, tattered shirt and a diaper. Important visitors and half dollars held no interest for him. Instead, he was focused on the remains of rice and cornbread scattered on the floor.”

Kennedy had ten children of his own. He tried to engage the boy.

“One of Kennedy’s sons, Max, was close in age to this child . . . . Instead of a curious toddler on the move, this child’s eyes were dull, his belly distended. Very little light filtered into the unlit room. Kennedy stroked the boy’s face and touched his stomach. He continued talking to the boy for two minutes or more, but the child remained listless and didn’t speak.”

Later that day, Kennedy would answer bluntly a hostile local editor. At Clarksdale, he would climb atop his sedan to address a cheering crowd. He would flash the fabled Kennedy wit at a house beside the road, at Winstonville by Mound Bayou. (“Are you really Mr. Robert Kennedy?” asked the man of the house, Andrew Jackson. “Yes, are you really Mr. Andrew Jackson?” asked Kennedy, with a grin.) But it was his encounter with little David White that mattered most.

Kennedy did not speak of his emotions – and Meacham does not speculate at length on what he felt – but what he saw had resonated. “We could be doing more for those who are poor, and particularly for our children, who had nothing to do with asking to be born into this world,” he told reporters, without smiling. “This is a reflection on our society, on all of us. . . . We might say that we’re doing what we should, but the fact is that we’re not doing what we should be doing.”

Mississippi is one of the most charitable states, Meacham observes; but “it is unlikely that at any point in Mississippi’s history charitable giving has ever matched the level of need.” The problem that Robert Kennedy framed remains a challenge that we have too often failed to meet.

Allen Boyer is HottyToddy.com’s Book Editor and the author of “Rocky Boyer’s War: An Unvarnished History of the Air Blitz that Won the War in the Southwest Pacific.”