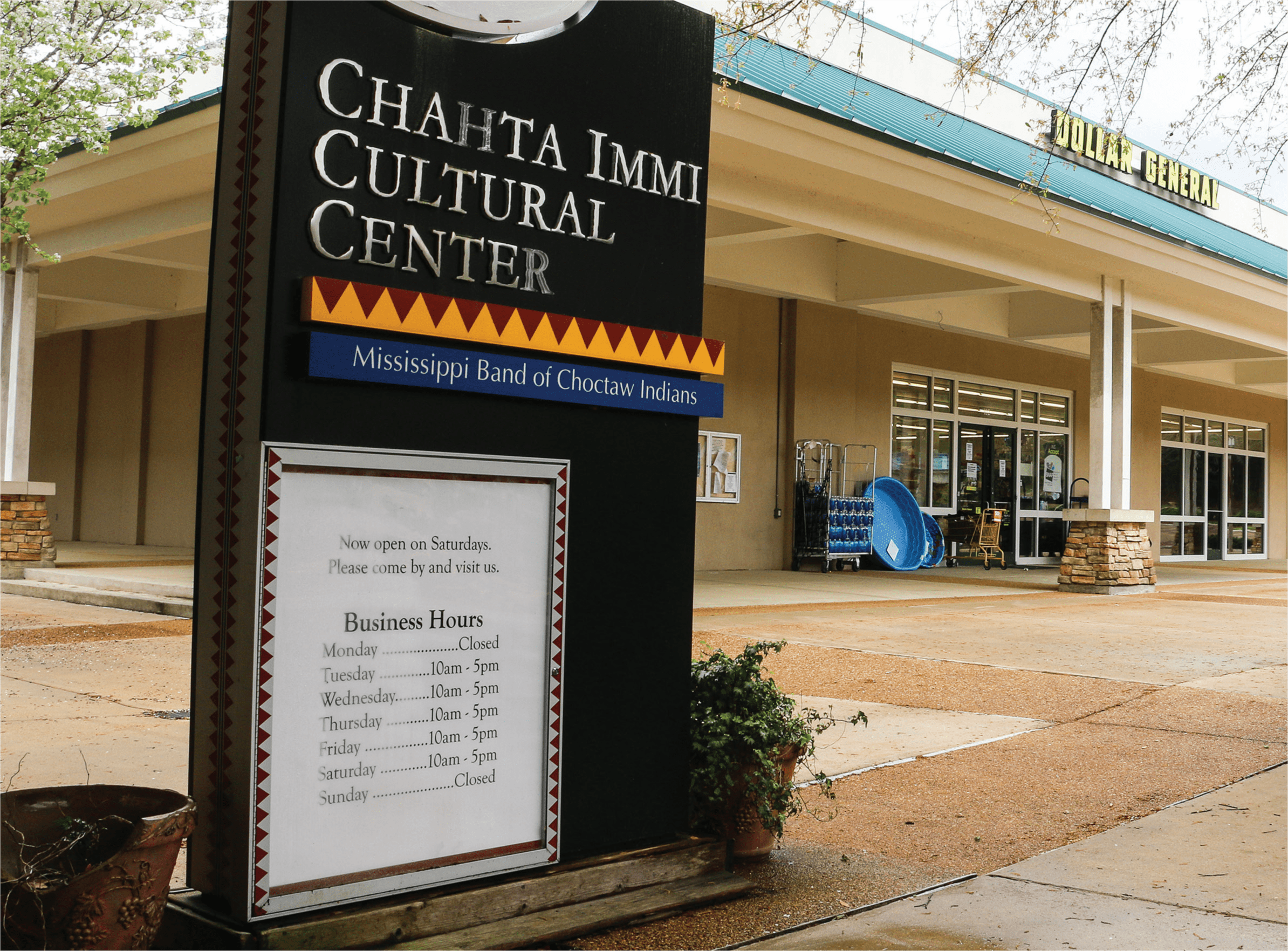

In the summer of 2003, a 13-year-old Choctaw boy went to work at a Dollar General store on the reservation as a part of his tribe’s Youth Opportunity Program, where an employer gets free labor in exchange for giving Choctaw youths work experience.

What started as a well-intended partnership became a nightmare. The store’s manager, Dale Townsend, was accused of molesting the boy during store hours.

And so began a legal squall that in the summer of 2016 would blow all the way to a divided, shorthanded U.S. Supreme Court. By the narrowest of margins, a 4-4 vote, the court on June 23 ruled in favor of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. In a terse, unexplained per curiam decision, the court upheld the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal’s ruling that the Choctaw tribal court had full authority to try civil suits filed by Choctaw plaintiffs against non-tribal businesses on the reservation. But just as important was the impact on tribes nationwide.

Tribes across the land immediately hailed what they saw as a victory for tribal sovereignty – the right of tribes to govern themselves, a complex legal issue perhaps dearer to tribes than any other. National Council of American Indians president Brian Cladoosby applauded the decision and added that “tribal courts must have the authority to protect and provide remedies for tribal members who are subjected to assault on Indian reservations.”

Mississippi Choctaw Chief Phyllis Anderson said the case affirmed “the sovereign right of Indian tribes to assert civil jurisdiction against a non-Indian entity in certain circumstances.” She called it “a positive outcome, not only for our tribe, but for all of Indian country.”

The case had been closely watched amid fears that a negative outcome would chip away at this coveted legal right for which tribes have been fighting for more than a century. If the Supreme Court had denied jurisdiction to the Choctaw court, it would have left such courts almost no basis for jurisdiction over non-tribal entities, even when they operate on tribal grounds. And tribal sovereignty would have suffered a major blow.

It all began with those allegations of abuse at the Dollar General store on the Choctaw reservation outside of Philadelphia.

Things became more complicated when the U.S. Attorney’s office, which rarely handles molestation cases, declined to prosecute Townsend on criminal charges. Indian tribes are not permitted to prosecute criminal cases in tribal courts against people who are not Indians.

Seeking justice, the boy’s family then filed suit against Townsend and Dollar General in tribal court. Dollar General then went to federal court, challenging the tribal court’s jurisdiction and arguing that Choctaw law could not be applied to a civil suit against someone who was not a member of the tribe even if the incident happened on the reservation.

But when Dollar General entered into its contract with the tribe, it had agreed to be bound by tribal courts in any dispute.

A federal district court in Mississippi and the Fifth Circuit in New Orleans both ruled that the tribe had jurisdiction. In fact, the Fifth Circuit found that Native American tribes have an inherent sovereignty predating the creation of the United States and that that sovereignty can be limited by congressional action only. And Congress has not removed the tribes’ authority to try civil cases that erupt on reservations.

Nevertheless, the U.S. Supreme Court sent shock waves through Indian Country when it agreed to hear Dolgencorp, Inc. v. Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. The justices heard oral arguments in December 2015. The high court — down to 8 members from its usual 9 because of a standoff between Congress and President Barack Obama — took months to deliver a decision. Even then, there was no explanation, not even a majority or minority opinion. The court simply affirmed the lower courts.

Any attack on the tribe’s power to control what happens on its own land is a sensitive matter for tribes who saw the U.S. break countless treaties and snatch millions of acres of land in the 1800s and 1900s. They well remember how President James Monroe, then-General Andrew Jackson and others promised tribes removed to reservations in the west that “no white man shall ever again disturb you” and that they would be protected “as long as water flows or grass grows.”

Native Americans got similar promises time and time again. And time and time again, they were broken. Even Chief Justice John Marshall’s ruling in 1832 that the Cherokee could not

be forcibly removed from their land was promptly ignored by Jackson. By then, the former general had been elected president. He was the principal architect of the Indian Removal Act that finally forced Southeastern tribes to abandon their homelands and move westward across the Mississippi River.

“The case is tremendously important since any ruling against the tribe will be applicable to all other Indian tribes in the country that currently hear and decide tort claims against non-members,” said attorney Joe Williams, who acts as legal counsel to Choctaw Chief Phyliss Anderson, shortly before the decision was announced.

In 1981, the Supreme Court heard Montana v. United States, in which the justices ruled that tribes and their courts have no authority over non-Indians except under two scenarios: “consensual relationships” and “activities that threaten the political integrity, economic security or the health and welfare of the tribe.”

Cheryl Hamby, assistant attorney general for the Choctaw, argued that the Dollar General case should fall into one of these exceptions. Dollar General did, after all, sign a contract with the Choctaw.

“We maintain that our tribal court has jurisdiction to hear this civil case brought by a tribal member against a non-Indian predominantly under the Montana rule,” Hamby said before the court ruled. “To deny the tribe’s jurisdiction in this area denies justice to this child and his family to have their case heard.”

According to Chief Anderson, denying the tribe’s jurisdiction would carry serious implications.

“Tribal sovereignty to me means that we lead our own path, that we lead our own destiny, that we can manage our own affairs,” she said. “I think that’s something that’s really important. I know that many times, people can use it in different ways. I choose to use it in a positive manner.”

And a fair one, Anderson argues.

“If a member of our tribe went off the reservation, abused her child, or if she was out there and she abused her husband, she would go to jail in Neshoba County,” Anderson said. So when someone who is not a member of the tribe commits a crime on reservation lands, why shouldn’t that person be similarly punished?

The battle for tribal sovereignty has raged ever since tribes ceded millions of acres of land to the U.S. in the 19th century. The government repeatedly broke its treaty promises and over time grabbed even more land from the tribes, making it available to outsiders. Since then, there have been numerous court battles over just how much authority tribes — “sovereign nations,” as Justice Marshall once put it — can wield on their own reservations.

Native Americans are particularly sensitive about their land and their children, especially when non-tribal courts try to take custody of Native American children. The issue goes back to the late 1800s, when tribes saw their children packed off to government boarding schools, where teachers punished them for speaking their own language and tried to wean them from their culture and traditions.

Sometimes, it gets complicated.

What happens if non-Choctaws go to state court to adopt a Choctaw child who may then grow up ignorant of the language or cultural ways of her ancestors? Is that legal? Should the child belong to her “new” parents she now lives with or those with whom she shares blood?

“Our future depends on retaining sovereign rights, land and land acquisition, and our children. A tribe literally has to have and protect these three resources for future survival,” Hamby said. “Studies show that Indian children suffer with identity issues when removed from their family and tribe and raised in non-tribal homes. Suicide rates in that instance are very high.”

It was because of this that the Indian Child Welfare Act was passed in 1978.

It mandates that “state courts must apply higher standards and take certain precautions to prevent the removal of these children and, if removal is necessary, to provide for reunification of these children with their family,” Hamby said. “When you think about it, sovereignty, land and children are critical for the future of tribes. We can’t afford to give up even an inch of our sovereign rights in any of those areas. That is why tribes will fight vigorously in court to protect their rights and interests in those three areas the most.”

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Child Welfare Act in 1989 in a case that stemmed from a Harrison County chancery judge granting custody of twin Choctaw children to non-Indian parents. The parents were residents of the Choctaw reservation but consented to adoption after the twins were born in Harrison County. The Supreme Court ruled that since the parents were Choctaw and actually resided on the reservation, Mississippi courts had no jurisdiction.

The high court found that Congress enacted the Indian Child Welfare Act because removal of Indian children from their cultural setting often stems from “cultural bias,” seriously affects the tribe’s long-term survival and can damage Indian children socially and psychologically.

Williams, the attorney and chief counsel to Anderson, said there are a number of reasons why tribal sovereignty should be fought for – for example, protecting the primary source of income for the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

“I would say that tribal sovereignty serves as an important backdrop to Indian gaming because the federal laws and regulations regarding gaming still recognize Indian tribes as the primary regulators of gaming activity on their lands,” Williams said. “And the economic development opportunities that gaming provides are to be used for essential tribal governmental programs and services and to provide for the general welfare of tribal members.”

But it doesn’t stop there.

“Another important element of tribal sovereignty is the right of Indian people to continue to carry on their native language, traditions and customs in their own way, even when those ways are frowned upon or considered unimportant by non-Indians,” Williams said.

Tribal sovereignty means all of these things. It means protecting children. It means financially supporting the tribe. It means continuing a culture.

Simply put, sovereignty is self-rule. As it applies to Native American tribes, it boils down to: Who decides what rules we must follow? Who decides what is taught in reservation schools? Who decides how natural resources are used? Who enforces contracts and resolves disputes? Who decides speed limits on reservation roads? When the answer is the tribe, a tribe has sovereignty. When the answer is anybody else, it does now.

And as the years have demonstrated, tribal sovereignty is not guaranteed. The Supreme Court, in several decisions since the 1970s, has issued rulings tribes see as encroaching upon sovereignty in worrisome ways.

Meanwhile, Anderson and tribal lawyers wait for the next legal shoe to drop. Presumably, Dollar General could lose the $2.5 million suit in tribal court and try to appeal yet again to the federal courts, stretching out the legal battle for some time. The chief knows the fight to preserve sovereignty is far from over.

“We have non-members that come onto our reservation and they tell us we cannot prosecute, we can’t hold them accountable to what they do to our people here on this reservation, to the Choctaw people,” she said.

“That’s not right. It shouldn’t be a hard sell, but it was. I know that in time we’re going to push for even more. We’re going to push for even more authority.”

By Anna McCollum. Photos by Chi Kalu

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw and Choctaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.