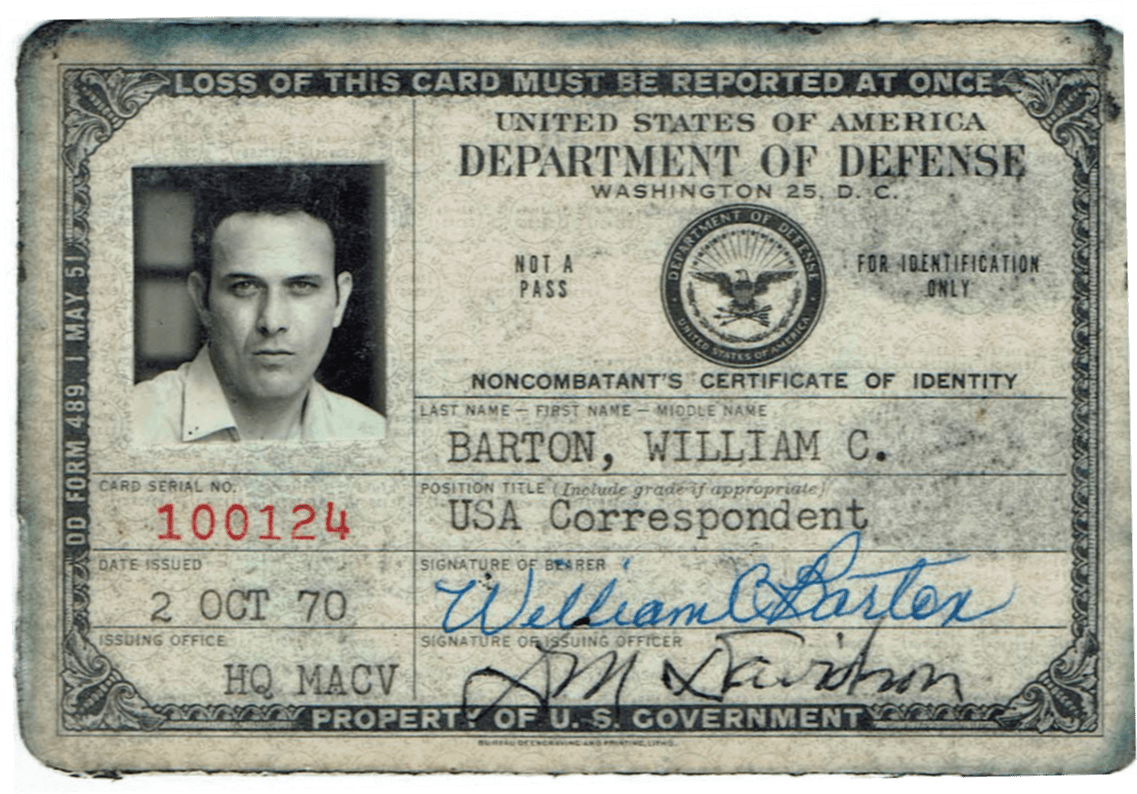

In the unpublished Vietnam diary of UPI correspondent Ted Marks, I finally found a reliable account of the tragic shooting of Bill Barton ’62, the subject of the biography I’m writing:

As we started to cross a bridge, … almost immediately someone started shooting. Barton said to me, “Are those shots” and then his head fell into my lap.

The shots continued so after a brief attempt to get the jeep off the side of the road, I put my foot on the floor and got the hell out of [there].

I continued until I thought I was out of range and then stopped. One look at barton [sic], though, and I figured I had better get help – fast. He had been shot in the head and the bullet had obviously exited through his right eye. He was bleeding profusely. My pants were soaked with [his] blood and what I believed were bone chips. …

Barton, meanwhile, had recovered consciousness somewhat, but was hysterical.

I don’t believe I’ll ever forget the sound of him trying to breath [sic] while I was driving with his head in my lap. It was a sucking, strained noise. I’ve been close to death before but that’s the first time I’ve ever heard death …

These words are only a portion of Marks’ March 14, 1971, journal entry. UPI did not issue a statement concerning this horrifying incident. Marks never spoke about it. He was the only witness.

Barton did not die that night in Saigon. But he would be dead in less than a year.

Marks died in 2012 before I could interview him, although I had found his name and contact information. My research eventually led me to his widow, who eventually found Marks’ journal and shared this entry with me. While his sobering words are almost unbearable, obtaining Marks’ account was a highlight of my research.

I knew Bill Barton. In Southerner-speak, my people and his people are from the same place. Today when I visit my parents’ graves in Pontotoc County, I can turn 180 degrees and face Barton’s.

Barton had captured my attention when I was an Ole Miss journalism student in the late 1960s. In my law and ethics of the press class, our textbook explained libel relating to race, nationality and patriotism in the segregated South.

Illustrating their point, the authors selected a court case, Barton v. Barnett. Barton had sued Gov. Ross Barnett (and others) for libel. Barton contended they conspired and published false accusations against him that embarrassed and humiliated him and that damaged him in his profession. He lost.

The lawsuit stemmed from the fact that Barton had become a “person of interest” to the Sovereignty Commission and Citizens’ Council, both organizations generally dedicated to preserving Mississippi’s traditions and way of life regarding segregation.

The reason for Barton’s targeting remains a mystery. The only concrete clue is a letter written as he returned to Oxford from his 1960 summer job at “The Atlanta Journal.” It charged: Bill was a communist; an NAACP member; a protégé of Ralph McGill, incorrectly identified as editor of “The Atlanta Journal;” and a friend of P.D. East, fiery editor of “The Petal Paper.” Harassment and intimidation followed this “confidential” letter becoming public.

Barton ran for editor of the “Mississippian,” Ole Miss’ student newspaper, in the spring campus-wide election, but he could not overcome these charges, each a lightning rod in the South. He lost.

Barton surfaced again in March 1971. I was working in Nashville when I heard on the radio, “AP correspondent shot in Vietnam.” I called the AP, asking if it was Bill. After repeated assurances I would not talk to the family, they confirmed it was.

Barton did not lose this one—yet.

Eventually, he returned home to live with his mother and try to figure out “whatever kind of life he might have.” The night before he was to start reconstructive surgery on his “bashed- in” skull, he went drinking, alone. He did not return. A week later, a farmer noticed something in his pond.

Meanwhile, I had discovered a “Mississippi Magazine” article that asked its former editors who had left the state if they would ever return. Barton had replied that he might someday “return to the land of my forefathers, but I’m not ready to be buried yet.”

In fewer than three years, he was buried there. My book had found its title—”Return to the Land of My Forefathers.”

This biography is significant for two reasons. Much has been written about Barton, most of it centering on events leading to the lawsuit, some mentioning his shooting and death. Most is contradictory; almost all cloaked in misinformation and mystery.

My goal is to craft this information into a compelling story, while trying to answer some of the questions. Barton had been an engaging, intelligent, young journalist from the South, whose short life was determined by the complexities of his own humanity as he confronted this country’s most controversial and divisive issues of the 20th century: civil rights and the Vietnam War.

This book remains viable in today’s social and political arena, in which people are struggling with—and divided by—change, diversity, equality, control, individual rights and war. My second goal is to give readers a glimpse of how such issues can affect anyone, as they did a Mississippi “farm boy” 50 years ago.

The number of primary sources still available surprised me. They have encouraged me and expressed gratitude for a book about Barton. People liked him and want to talk about him, and remembering has been bittersweet. Expressing genuine affection for the person they remember, they have been open and judicious.

Journalists who knew Barton have been generous and gracious with time, information and contents. Through the internet and social media, I found the only living Saigon AP bureau chief, and he was Barton’s bureau chief. The AP and Barton had ended their relationship earlier in the day, but the news bureau still got the call that night when Barton was shot. I’ve talked with the AP correspondent who answered that call. And, I’ve talked with a UPI correspondent who was with Barton that night, which began at the Melody Bar, aka the UPI bar.

But it was a primary source from Barton’s Mississippi struggles, seemingly where Barton’s controversial trajectory began, who affirms the veracity of Barton’s lawsuit. “He was blackballed from working in the state of Mississippi,” says veteran journalist Bill Minor. Minor’s explanation will be in the book.

Jennifer Bryon Owen, ’69, holds a BA in journalism and English with a minor in history. After a career in communications, she is devoting her time to writing. To learn more, go to her website at jbowrites.com.

Jennifer Bryon Owen, ’69, holds a BA in journalism and English with a minor in history. After a career in communications, she is devoting her time to writing. To learn more, go to her website at jbowrites.com.

The Meek School Magazine is a collaborative effort of Journalism and Integrated Marketing Communications students with the faculty of Meek School of Journalism and New Media. Every week, for the next few weeks, HottyToddy.com will feature an article from Meek Magazine, Issue 5 (2017-2018).

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.