Featured

Emmerich: Lawsuit Says Mental Patients Raped, Abused at Meridian Prison

At the federal courthouse in Jackson, East Mississippi Correctional Facility is defending itself against a lawsuit claiming atrocious conditions for its inmates.

At the federal courthouse in Jackson, East Mississippi Correctional Facility is defending itself against a lawsuit claiming atrocious conditions for its inmates.

The facility, just south of I-20 six miles west of Meridian, was built in 1999 to house 1,500 inmates. It specialized in housing the mentally ill.

Taking care of the mentally ill has always been one of the greatest challenges of a civilized society. Over the centuries, horror stories of genuine hell houses have been a never-ending blight on modern society.

So how did a prison become a mental health facility? The answer lies in the age-old problem of unintended consequences.

Forty years ago, media exposes of the horrific conditions of mental institutions led to a nationwide movement to shut them down. This movement was highlighted by the 1975 movie, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” starring Jack Nicholson, who won an Academy Award for his performance of a brilliant, eccentric person whose ultimate fate was a lobotomy, which turned his lovable character into a zombie.

An emotional scene from “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest”

The movement released hundreds of thousands of mentally ill people to roam the streets. You can still see them wandering aimlessly on many street corners today, talking to themselves and often getting into conflicts with the law.

The plan was to have more humane, smaller local mental health facilities. To some extent this has happened. But the best laid plans of mice and men are easily led astray. Mounting needs and budget crunches shortcircuited the benevolent vision.

So what happened? Our prison facilities have become the de facto mental institutions for hundreds of thousands of mentally ill people. We are back to where we started, but even worse because prison guards lack basic mental health training that once partially existed at our closed mental institutions. We are worse off than when we started.

Even worse, a large percentage of the mentally ill cannot be legally sent to state prison so they linger in county jails where they are inhumanely subjected to cruel treatment by ill-trained guards. Our jails are overwhelmed.

If these ill people are forcibly medicated, then they can temporarily become non-threatening to themselves or others, which means by law, they must be released. Once free, they stop taking their medications, and the whole process starts over.

This is a sad state of affairs. There are many terrible diseases, but mental illness is probably the cruelest and the most difficult to deal with.

All the experts know what is needed: Modern, clean facilities where trained experts can compassionately treat the victims. There should be gardens and walking trails and organized activities. Patients should be genetically tested to find what drugs are most suitable. Intensive personal therapy combined with cutting-edge drugs could save many of these lives with the ultimate goal of reintegration into society.

But it is not so for one reason: Money. Such modern, humane treatment is exorbitantly expensive, and our society has not deemed this a priority. So, instead, we have the East Mississippi Correctional Facility (EMCF.)

“Hell on Earth”: Check out this report on the “horrific conditions” at East Mississippi Correctional Facility near Meridian.

Like early childhood education, properly treating mental illness would save billions in the long run. But the politics of the world make it almost impossible to happen. Many mentally ill people end up committing suicide. Authored by Ron Powers, “No One Cares About Crazy People: The Chaos and Heartbreak of Mental Health in America,” is an excellent book that chronicles this crisis in our country.

This is a disaster of huge proportions. One in 10 people will suffer serious mental illness at some point in their lives. The economic toll is billions upon billions.

Often treatment is left to the family, if the mentally ill person is blessed enough to have one. The emotional and financial burden of dealing with a mentally ill family member is devastating. One of the first pieces of advice to family members struggling to help is to seek mental health counseling for themselves lest they also become overwhelmed.

There are genetic factors behind mental illness, but environmental stress can be the trigger. As our society becomes increasingly chaotic and stressed, mental illness is reaching epic proportions.

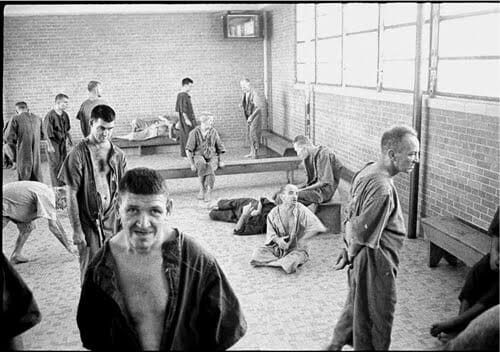

This image portrays life for patients in an old Louisiana state hospital for the mentally ill.

EMCF is run by a private company, Management & Training Corporation, based in Utah. It’s the third largest private prison company in the country. Attorney General Jim Hood is suing the company because of its involvement with the Chris Epps bribery scandal.

In 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Southern Poverty Law Center filed suit to force improvements at EMCF. The suit alleges a range of horrors that have plagued mental institutions forever: rapes, beatings, cruelty, failure to medicate. As part of the evidence reviewed by Judge William Barbour, a captain at the prison said in a deposition that prisoner-on-prisoner violence was commonplace, that corrections officers were poorly trained, and that guards facilitated inmate violence by opening cell doors and then failed to intervene when prisoners were assaulted.

Guards arranged for prisoners to attack one another, ignored fires set by inmates to signal distress, and allowed prisoners to trade whiskey and cellphones. Mentally ill were locked in solitary confinement for weeks at a time. Plumbing failures. Roaches. Filth. Rats. Watered-down gruel. One mentally ill patient sliced himself up and was left for hours on his cell floor to bleed to death. The list of atrocities is long.

Time marches on. There is nothing new under the sun. The horror of EMCF is repeated time and time again, especially in poorer places where money is lacking.

Let’s hope this lawsuit can make some small dent in our collective consciousness. Let’s hope that, in the march of progress, civilized society can one day learn to care for the mentally ill like we do those suffering from heart disease and cancer.

Wyatt Emmerich is president of Emmerich Newspapers, Inc. in Jackson.

Wyatt Emmerich is president of Emmerich Newspapers, Inc. in Jackson.