Arts & Entertainment

Review: "The Afterlives" Bends Reality in Funny But Provocative Ways

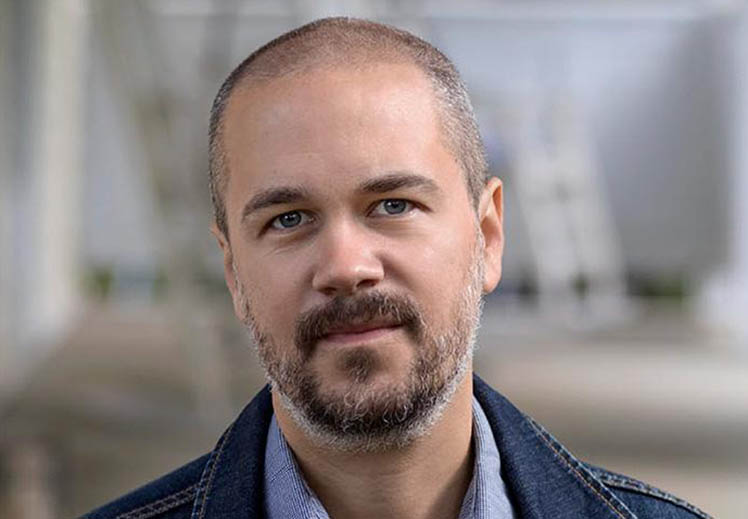

“The Afterlives.” By Thomas Pierce. Riverhead Books. 366 pages. $27.00.

“The Afterlives,” by Thomas Pierce, is a cheerful, clever novel about past and future lives. Pierce has published short stories in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The Oxford American, and this debut novel is an awfully good book.

The narrator is Jim Byrd, a young bank loan officer in Shula, North Carolina. Following a heart attack, he lives with a medical device installed around his heart: “a HeartNet, a very advanced implantable defibrillator that looks a bit like a small onion bag only with tighter mesh … If never powered down, HeartNet will keep my heart beating for as long as its battery allows. About two hundred years, apparently.”

Checking out a loan application from Su Casa Siempre, a local Tex-Mex restaurant, Jim runs into Annie, a girl he once dated in high school. They fall in love, marry, have a child and live together for more than twenty years.

Intermittently, intrigued by reports that Su Casa Siempre is haunted, Jim looks up the history of the building. He finds that a couple who lived there in the 1920s died following a fire. As he searches further, he ultimately decides to test a “Reunion Machine,” a device that can “bend you away from this life and toward the next.”

In “The Afterlives,” there are no undead: no vampires, no Ringwraiths. Nor are there zombies, but Shula, like other towns in the Blue Ridge Mountains, is overrun by a different horde of all-devouring strangers: the White Hairs, transplanted retirees in pastel polo shirts and khaki shorts. Beyond the White Hairs, Pierce imagines a new population overwhelming the community: Businesses move one short step beyond flat-screen TV videos, projecting holograms in their storefronts and showrooms to replace greeters and salesmen. “They were immigrants from another dimension,” Pierce writes.

In “The Afterlives,” there are no undead: no vampires, no Ringwraiths. Nor are there zombies, but Shula, like other towns in the Blue Ridge Mountains, is overrun by a different horde of all-devouring strangers: the White Hairs, transplanted retirees in pastel polo shirts and khaki shorts. Beyond the White Hairs, Pierce imagines a new population overwhelming the community: Businesses move one short step beyond flat-screen TV videos, projecting holograms in their storefronts and showrooms to replace greeters and salesmen. “They were immigrants from another dimension,” Pierce writes.

“Corporate shills. Ad campaign faces … Hawkers of form-fitting mattresses and intelligent thermostats. Sometimes they were recognizable, even famous. Tom Bradys now stood outside every Subway in America, suave, confident, doing their best to lure you inside for a delicious foot-long turkey and provolone on wheat.”

Pierce suggests that afterlife, like life, is what we make of it—or that the difference may be only a matter of perspective. Any phase of life may count as an afterlife: as the Semisonic song, “Closing Time,” puts it, “Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end.” Su Casa Siempre used to be a private home. The Church of Search meets at the old Masonic Temple. Jim’s parents, happily married for decades, recall the moment they met at a party, but as their son observes, both of them came to the party with other dates. Shula was once a resort town; now it caters to White Hairs and hipsters.

Reading “The Afterlives” is like watching “The Twilight Zone.” Rod Serling was grave and brooding, while Pierce is amiable and funny, but he raises questions that are just as surreal and provocative.

If you were revived after your heart stopped, were you ever more than clinically dead? Are you presently more than clinically alive?

Assuming that all moments are equally present in eternity, if people alive in the present attempt to contact people who lived in previous eras, won’t we alarm and frighten them when we manifest ourselves? Who is haunting whom?

What happens when a hacker breaks into the HeartNet worldwide monitoring system?

As a matter of business expenses, should exorcists’ fees be lumped together with exterminators’ charges?

If a husband and wife both experiment with the Reunion Machine, which would undermine their marriage more: her reunion with her dead first husband or his glimpse of his future second wife?

The border between life and afterlife may be a shifting line. Pierce imagines deceased rock stars touring once again in holographic form: “Prince performed a sold-out show at the theater in downtown Shula, and I overheard a guy ask his date, earnestly, why Prince hadn’t put out any records in so long.” That may be fiction, but this week, the New York Times reports a music magnate’s plans to send out on tour a hologram of pianist Glenn Gould, who died in 1982.

The border between life and afterlife may be a shifting line. Pierce imagines deceased rock stars touring once again in holographic form: “Prince performed a sold-out show at the theater in downtown Shula, and I overheard a guy ask his date, earnestly, why Prince hadn’t put out any records in so long.” That may be fiction, but this week, the New York Times reports a music magnate’s plans to send out on tour a hologram of pianist Glenn Gould, who died in 1982.

Fittingly, Pierce reminds us that hologram projectors and Reunion Machines are not the only devices that can bend reality and confront us with a pageant of insubstantial visions. In “The Afterlives,” the narrative leaps back and forth across decades, speaks in past tense while sliding from the present into the future, sums up a life’s worth of experience in a form that readers can absorb in a single day. In every sense, Pierce demonstrates, a novel can be a fantastic thing.

Allen Boyer, a native of Oxford, is the Book Editor of HottyToddy.com.

Allen Boyer, a native of Oxford, is the Book Editor of HottyToddy.com.