For all his worldliness and erudition, Willie Morris—the late Mississippi memoirist, editor, educator and literary lion of the South—loved nothing more than a good telephone prank.

And when he struck, he usually struck at night.

“He was very mischievous with the phone,” recalled his longtime friend, Ole Miss journalism professor Curtis Wilkie, in a 2009 interview with the now-defunct Oxford Enterprise. “He got me once; he never got me again.”

Late one night, Wilkie, then a reporter for The Boston Globe, got a call from a man identifying himself as an Associated Press reporter. “He was calling me for a comment on something that had never happened—a mythical story about the president of Boston University getting into a fight with the president of Harvard and biting him on the leg.”

Blame it on the late hour, but Wilkie took the bait. “I provided some speculation as to what might have happened,” Wilkie recalled, chuckling. “After about five minutes of me pontificating on the subject, he started laughing and said, ‘This is Willie.’”

“He’d make these calls late at night,” Wilkie added. “He tried it on me more than once after that. Any call I’d get after midnight, I would know it was Willie.”

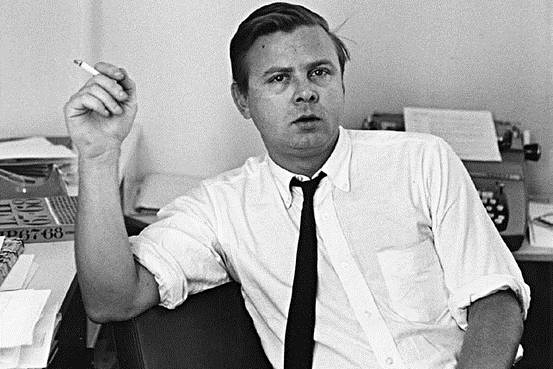

Round-faced and impish, a dimple-chinned, roly-poly Rhodes Scholar who liked his booze perhaps a bit too much, the Yazoo City-born Morris served as Ole Miss’ writer-in-residence throughout the 1980s. A former editor of Harper’s magazine and author of more than a dozen books and numerous articles and essays, Morris earned his fame by writing evocatively, candidly and tenderly about the South he loved—and influenced several generations of fellow writers who revered him.

Round-faced and impish, a dimple-chinned, roly-poly Rhodes Scholar who liked his booze perhaps a bit too much, the Yazoo City-born Morris served as Ole Miss’ writer-in-residence throughout the 1980s. A former editor of Harper’s magazine and author of more than a dozen books and numerous articles and essays, Morris earned his fame by writing evocatively, candidly and tenderly about the South he loved—and influenced several generations of fellow writers who revered him.

If not for a heart attack that struck him down Aug. 2, 1999, Morris would have been 83 today. Very likely he would have marked the occasion with a jug of wine, a pack of cigarettes and a small army of friends and possibly a few strangers.

His fame and stature aside, the man was nothing if not approachable. An unabashed barfly who held court at Oxford watering holes like the Warehouse and the Hoka, Morris welcomed everyone to his table.

“He was very friendly to everyone,” Wilkie said. “There was nothing at all condescending about him. Even though he was a Rhodes Scholar, he never felt like he was intellectually better than anyone else. He enjoyed the company of all sorts of people.”

Additional reading: How Willie Morris learned to love his cat.

Wherever Morris lived—Oxford, Jackson in his last years, or New York, where he served a brief and stormy tenure as Harper’s youngest-ever editor in the late 1960s and got shown the door for being too liberal—a sort of literary salon sprung up around him.

At Harper’s he nurtured or boosted the careers of such literary nobles as William Styron, Norman Mailer, Walker Percy, David Halberstam, John Updike and Bill Moyers.

James Dickey, James Jones and Winston Groom called him a friend. At Ole Miss, Donna Tartt studied at his feet, as did John Grisham.

But it was Morris’ own writing that made him a legend. From engaging childhood memoirs like “Good Old Boy” and “My Dog Skip” to more sober works like “The Ghosts of Medgar Evers,” Morris wrote movingly about the people and places he knew best.

He wrote about football and baseball, too, about dogs he had loved and lost, about a cat named Spit McGee with one blue eye and one golden eye.

But the best of his work was serious, weighty stuff—race, integration, civil rights, the plight of working-class southerners. He may have loved Mississippi so much that he needed to leave it for a while—hence his years in New York and Texas (where he attended college)—but he never put it behind him.

Additional reading: See Willie Morris’ handwritten note about Marcus Dupree from the Ole Miss archives.

“Wilkie and I both left the South and came back,” Wilkie said. “He was, in many ways, the midwife for my book, ‘Dixie,’ which dealt in part with some of the things he had wrestled with in his own books: the idea of leaving the South and yet being drawn back to it.”

“We both felt strongly about the sense that we were southern,” Wilkie continued. “For all the problems that the South was going through back then … we never really left the place mentally. That’s really the overarching theme of Willie’s body of literature—his tortured love of the South.”

At Harper’s, Morris published articles that showed a side of the South that the world had never seen. “I think it was the first national magazine that ran articles about the Deep South,” Will Norton, dean of the UM School of Journalism and a friend of Morris’, told the Oxford Enterprise in 2009. “He had articles about Richard Petty and (singer-comedian) Brother Dave (Gardner)—all these things that we had never read about in any of the national magazines. I think he introduced a lot of Americans to the Deep South, and it was such fascinating writing.”

But for a self-proclaimed “good old boy,” Morris was no flag-waving traditionalist. “He was not afraid to voice his opinion if he believed he was right,” another friend and UM journalism department colleague, Samir Husni, said in 2009. “And he was not afraid to give space to other writers if their opinions matched his own. He was more like a crusader. He had a cause, and he went after it.”

Forced to resign from Harper’s when conservative advertisers began to balk at the content, Morris eventually came home in 1980 and settled in to teach at Ole Miss. Here, he helped groom a new generation of young writers, albeit in his own unconventional style. He preferred to teach his classes at the Warehouse with a cocktail in hand. “People would call for him, and we’d give them the number for the Warehouse,” Husni recalled.

Forced to resign from Harper’s when conservative advertisers began to balk at the content, Morris eventually came home in 1980 and settled in to teach at Ole Miss. Here, he helped groom a new generation of young writers, albeit in his own unconventional style. He preferred to teach his classes at the Warehouse with a cocktail in hand. “People would call for him, and we’d give them the number for the Warehouse,” Husni recalled.

But Morris’ air of conviviality masked a darker outlook. “He was this guy who wrote these optimistic pieces, but, deep down, that’s not how he looked at the world,” Norton said. “He wrote of this fairy tale world because he wanted to cover up the horror movie of real life that he saw … I really think that, in many ways, Willie was a very tortured person. And—I really liked this about him—he was such a vulnerable person.”

Additional reading: Will Norton shares his memories of Willie Morris.

Morris apparently found some relief from his inner anguish when, in 1990, he married his second wife, JoAnne Prichard, and moved to Jackson. The marriage suited him, friends said, and one of his last books, “My Dog Skip,” suited Hollywood. It became a hit movie starring Kevin Bacon, Diane Lane and Frankie Muniz.

Morris reveled in the experience of seeing his book brought to life on film, but he died before the final version was released in 2000.

And in his death, as in his life, friends and fans, famous and unknown, thronged about to see him one last time. He became the first writer in Mississippi’s history—and only the third person in the 20th century—to lie in state in the Rotunda of the Old Capitol building in Jackson.

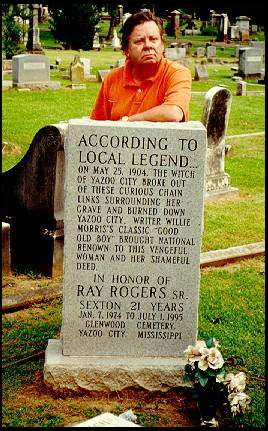

As admirers praised and mourned him in obituaries nationwide, the mischievous, chubby-cheeked provocateur was laid to rest in a Yazoo City cemetery, just 13 paces, it is said, from the grave of the Witch of Yazoo, a character he’d described in amusing detail in “Good Old Boy.”

William Faulkner may be Oxford’s most honored literary icon, but Morris was, without a doubt, its most beloved.

“Faulkner never did anything for Ole Miss,” Wilkie said. “He had this great presence, everybody was proud of him, but he never brought his contemporaries here to share them with the townspeople. Willie loved to bring people like Plimpton and Styron to Mississippi and show it off. He was proud of this place.”

Rick Hynum, the editor-in-chief of HottyToddy.com, originally wrote this story for The Oxford Enterprise in November 2009.