Arts & Entertainment

Review: Jesmyn Ward's "Sing, Unburied, Sing" Reminiscent of Larry Brown

Jesmyn Ward poses for a portrait outside her great-grandmother’s house in Pass Christian, Miss.

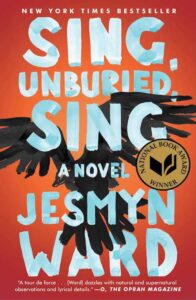

“Sing, Unburied, Sing.” By Jesmyn Ward. Scribner. 291 pages. $26.00.

Novelist Jesmyn Ward, from DeLisle in Harrison County, won a National Book Award for her 2011 novel, “Salvage the Bones,” a story wrapped around Hurricane Katrina. “Sing, Unburied, Sing,” her most recent book and a very accomplished novel, has won Ward a second National Book Award—and rightly so.

“Sing, Unburied, Sing” is told in chapter-length monologues. One speaker is Leonie, a young black woman of rage and wit and a bad drug habit, who wants to be a better mother than she ever will be. Another is Jojo, her teenage son, who cares ceaselessly for his sick toddler sister Kayla. The book follows their drive from a backwoods hamlet on the Gulf Coast to the penitentiary at Parchman (to pick up Michael, who is Jojo and Kayla’s white father) and home again. Another narrator, Richie, who joins them at Parchman, speaks from beyond the grave.

Ward embroiders freely the traditional elements of Southern Gothic melodrama. This book features angry young black men, shiftless white trash, shootings, lynchings, dark woods, and a brutal sun-baked prison camp. There are ghosts, two of them and more, souls of lost black folk. (Readers may recall Ward’s memoir, “Men We Reaped,” her recollection of five young black men from her hometown in Delisle who died too soon, from drugs or accidents or by their own hand.) There are road-houses; there is intoxication—crystal meth, not whiskey. In the borders of the story hover symbolic buzzards, elders who speak Creole and practice vodûn, and gentleman lawyers, down-at-heels but amiable and cultured.

There is plenty of brutality in this book. Racism too, although this is a modern world, where black youths can be high-school football stars before violence cuts them down. Whatever was mythic or nourishing has been corrupted. Leonie’s mother Philomène practices folk medicine. That might be picturesque, except that it is tragic: her herbs did not stop the cancer that is killing her. Leonie can talk with spirits, but only when she is high on drugs; visions come as hallucinations. The saltwater beaches and marshland have been sullied by oil gushing out from the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

There is plenty of brutality in this book. Racism too, although this is a modern world, where black youths can be high-school football stars before violence cuts them down. Whatever was mythic or nourishing has been corrupted. Leonie’s mother Philomène practices folk medicine. That might be picturesque, except that it is tragic: her herbs did not stop the cancer that is killing her. Leonie can talk with spirits, but only when she is high on drugs; visions come as hallucinations. The saltwater beaches and marshland have been sullied by oil gushing out from the Deepwater Horizon disaster.Language is failing. A bedtime story starts in the world of Brer Rabbit, shifts into Goldilocks, sounds a hopeful note—and ends in silence, not only because the child has fallen asleep. A noble phrase used by Martin Luther King is now bandied about by lawyers seeking deals for their clients.

Ward’s ghosts are often mute or go unseen. When they speak, they can be lyrical. And in this book, that may be misplaced. Ward’s real talent is for realism. She never misses a note when Leonie rants in anger or resents that what Philomène taught her cannot help Kayla.

“If the world were a right place, a place for the living, a place where men like Michael didn’t wind up in jail, I’d be able to find wild strawberries. That’s what Mama would look for if she couldn’t find milkweed. I could boil the leaves at Michael’s lawyer’s house … [But] this is the kind of world it is. The kind of world that gives you a blackberry plant, a doughy memory, and a child that can’t keep nothing down. I kneel by the side of the road, grab the thorny stems as close to the earth as I can get them, and pull, and the vine pricks my hand, tears at the skin, draws blood in tiny points that burn.”

Ward can draw a scene in a handful of lines. You feel the dinginess of a gas station and the tenseness when a young policeman makes what he thinks is a routine traffic stop. When Kayla is sick, you can smell the acid stink of vomit.

Ward can draw a scene in a handful of lines. You feel the dinginess of a gas station and the tenseness when a young policeman makes what he thinks is a routine traffic stop. When Kayla is sick, you can smell the acid stink of vomit.Some reviewers have likened Ward to Toni Morrison; she should be compared with Bobbie Ann Mason and Larry Brown. Her energy has carried her far already. The starkest, most unexpected vignette in this book looks across decades and even across genres. It deals with Kinnie Waggoner—in this book, as in history, the deadliest trusty and manhunter ever employed at Parchman. In barely a page, Ward gives a full portrait of the man, fierce and feral and indomitable, a man “lawless in the lawless South.” There is nothing here of “Beloved” or “Song of Solomon.” It is a Western scene as harsh and mythic as anything in “Lonesome Dove” or “Blood Meridian”—or “The Unvanquished.”

Ward is a challenger, and her next book will be worth reading.

Allen Boyer, a native of Oxford, is the Book Editor for HottyToddy.com.