Arts & Entertainment

Larry Wells Walks in Novelist Alistair MacLeod's Footsteps on Cape Breton

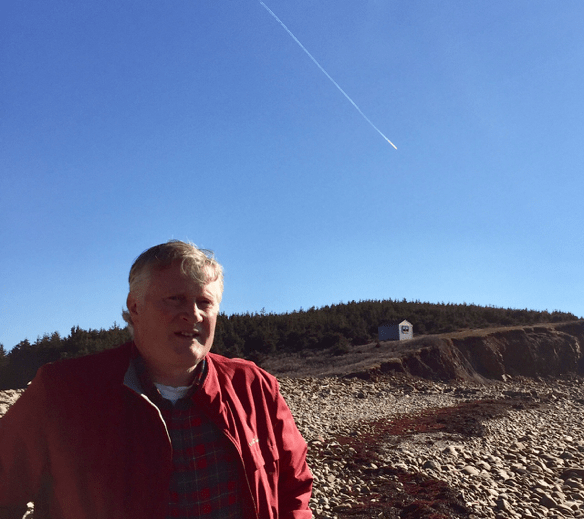

Alistair MacLeod on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Photo from TV documentary, “Reading Alistair MacLeod”

With his little dog Blossom at his side, Gil Macleod, a native of Cape Breton Island who is related to novelist Alistair Macleod, is leading me to his cousin’s writing shack overlooking the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Here is where Macleod penned his classic novel, “No Great Mischief,” (1999) about Cape Breton fishermen and miners and their Scottish ancestors who migrated to Nova Scotia in the 18th century. His other works include “The Lost Salt and Gift of Blood” (1976), “As Birds Bring Forth the Sun and Other Stories” (1986), and “Island” (2000).

In MacLeod’s stories, fiction and history are inextricably intertwined, and the literary pilgrim comes to Cape Breton Island expecting to find landmarks immortalized in his stories. “No Great Mischief,” published when he was 63, tells the story of the clan Donald’s emigration to Canada, led by patriarch “Calum MacDonald” during the Highlands Clearances. Driving north on Highway 19 from the Canso Causeway and winding along the coast, I’ve been keeping an eye out for “Calum Ruadh’s Point,” the fictional burial place of redheaded Calum MacDonald, which is worn away by storms “as if his grave is moving out to sea.”

Tall, blonde, and plain-spoken, Gil MacLeod warns against a literal interpretation of his cousin’s works. “People asked him all the time, ‘Is that where such and such happened? Is that bluff Calum Ruadh Point? Is that where the boy’s parents fell through the ice and drowned?’ And he said again and again, ‘It’s fiction. It’s not real. I made it up!’” Yet, although fictional characters and places are imaginary, MacLeod’s stories of third- and fourth-generation Scottish immigrants’ hardships in a starkly beautiful but unforgiving landscape are based on rock-solid reality. He once said of his works, “These are not true stories, but they’re real stories.”

Tall, blonde, and plain-spoken, Gil MacLeod warns against a literal interpretation of his cousin’s works. “People asked him all the time, ‘Is that where such and such happened? Is that bluff Calum Ruadh Point? Is that where the boy’s parents fell through the ice and drowned?’ And he said again and again, ‘It’s fiction. It’s not real. I made it up!’” Yet, although fictional characters and places are imaginary, MacLeod’s stories of third- and fourth-generation Scottish immigrants’ hardships in a starkly beautiful but unforgiving landscape are based on rock-solid reality. He once said of his works, “These are not true stories, but they’re real stories.”Alistair MacLeod (1936-2014) was born in Saskatchewan. His parents moved to Alberta, where his father worked in the coal mines, then returned to the MacLeod homestead on Cape Breton Island when Alistair was ten. He grew up in the Dunvegan farmhouse his great-grandfather built in the 1860s.

Alistair McLeod’s family home in Dunvegan, Inverness County

Gil MacLeod’s path to the writing shack leads through a forest of white birches. Across the trail dead trees guard MacLeod’s right to privacy. We step over the downed trees, ford a stream by walking on a log, and emerge on a beach strewn with rocks and boulders. In the near distance on a bluff overlooking the Gulf of St. Lawrence stands the writer’s shack where Alistair Macleod wrote many of his stories.

The cabin, or “shack” as Gil calls it, is surrounded by thick ground cover that smells like juniper. The one-room shack has a fecund, creative quality common to writer’s havens. No electricity. No phone. A plywood board for a writing desk. A folding chair. Silence, sunlight and stories waiting to be told.

Alistair Macleod’s son, Alexander, a professor at St. Mary’s University in Halifax whose short story collection, “Light Lifting,” was selected 2011 Globe and Mail Book of the Year, reiterates his cousin’s caution. “When you look out the window, this is the island you see,” he says. “But the figurative island is much more important than the actual one. Although he looked at Margaree Island a lot, and it dominates the view from our house [the MacLeod home just up the road], he was not writing about that particular island in a strictly realistic way. Yes, he was certainly interested in islands, and especially in all their metaphorical possibilities, but he was never trying to accurately represent one particular island. ‘Everybody has experience,’ he used to say, ‘but not everybody can make art.’”

Gil MacLeod stands on the beach below his cousin Alistair’s writer’s shack.

In anchoring his fiction in geographical places, MacLeod was following an honored literary tradition. Two of his idols, Thomas Hardy and William Faulkner, drew maps of their fictional counties. Hardy borrowed the name “Wessex” from an Anglo-Saxon kingdom located in the south of England. Faulkner discovered the Chickasaw Indian name “Yoknapatawpha” on an old watershed map of Lafayette County, Mississippi. Much is to be gleaned from encountering landmarks one first came to know as fictional settings. I read “No Great Mischief” in Oxford, 2,000 miles from Cape Breton, and yet when I got there, I was no stranger to MacLeod country. This is the magic of fiction. For Cape Bretoners, as for lifelong residents of Hardy’s Dorset and Faulkner’s Lafayette counties, a charged landscape comes with the territory.

My search for MacLeod’s fictional landmarks grows legs when I meet MacLeod’s longtime friend, Alice Freeman. “Every time we look at the island [Margaree Island in the Gulf of St. Lawrence], we say that’s the island in ‘No Great Mischief,’” says Freeman, speaking at her gift shop on Central Avenue in Inverness. “Remembering the old things can be kind of creepy, actually, but he [MacLeod] told it like it was. One grandfather was rough and tough, and the other was proper. The grandfather on this side liked his drink, and the grandmother liked her church. Alistair was a character himself. Always dressed up and wearing his cap.”

When asked about the archetypal Calum Ruadh Point, Freeman suggests a likely spot. “There’s a point out from his house. The road is very rough. You’d break an ankle if you tried to go there.” As vague as this description may be, to one who would walk in MacLeod’s footsteps no clue is to be discarded.

Photo by Kathleen Wickham

In “No Great Mischief,” the narrator, Alexander MacDonald, is orphaned when his parents, keepers of a lighthouse, fall through the frozen ice of the bay and drown. Locals believe that MacLeod drew on an actual drowning at Margaree Island. Rankin MacDonald, editor of The Oran newspaper in Inverness, points out that the real victims’ son, like the fictional Alexander, was reared by relatives: “The son, Herby, still lives here. Herby’s a fisherman. Well, he’s retired now. But it was his parents [who drowned]. And then he was brought up by somebody else, relatives. We know who we are in our hearts and among ourselves, but then when [MacLeod] articulated it, we said, ‘That’s about my way of life. These are my people.’ And that’s what I think stirs in the hearts of everyone here, why we loved him so much.”

Learning of my search for a Calum Ruadh Point, Rankin MacDonald recalls a family cemetery on a bluff where a Scottish emigrant left instructions to be buried facing his homeland. MacLeod’s epic novel was based on his Scottish family’s emigration and their struggle to survive as fishermen.

Intrigued by MacDonald’s suggestion, I set out to find the Scottish gentleman’s grave. Half an hour later, I am driving along a high ridge overlooking the beach community of Inverness. The county roads can be confusing, but an elderly gentleman in a pickup truck stops to show me the way. In drizzling rain I tramp the woods and fields searching for an overgrown cemetery. My search proves fruitless but nevertheless is strangely satisfying. But I’m not done yet.

At the Downstreet Café, a local gathering place, Cape Breton author Frank Macdonald appreciates and perhaps sympathizes with my literary-landmark-compulsion. “Alistair does a very good job of not identifying a specific place, but the geography is so accurate and what he describes is all around here. You can walk to it, and it’s just around the next bend on the shore.” Yet, he adds, “MacLeod was adamant that these were creations, not actual places. He did a remarkable job of universalizing these people while keeping them so tremendously real, and you would expect to run into them on the street or in the tavern or in the mines.”

When I ask about Alistair MacLeod’s slow-but-sure writing technique, Frank Macdonald tells how his friend once came to him brimming with good news: “How much he saw ahead, what was coming, I don’t know, but at one point he did say, ‘I got the end of the book this week.’ This was three or four years before [the novel] was published,” adds Macdonald, “and it was probably the last sentence in ‘No Great Mischief’: ‘All of us are better when we are loved.’ He knew where he was going with it.”

MacLeod’s burst of inspiration could well have happened in the writer’s shack, bare bones and functional, a ray of sunlight blazing on the floor like spontaneous literary combustion. I recall looking out the window and seeing what the author saw when he glanced up from his tablet. Alice Freeman’s words reverberate—there’s a point out from his house—his writing shack, she meant, where the salt-stained window reveals Margaree island shining in the sun, and just north of the shack a point of land facing the sea as if rushing out to meet it.

MacLeod’s burst of inspiration could well have happened in the writer’s shack, bare bones and functional, a ray of sunlight blazing on the floor like spontaneous literary combustion. I recall looking out the window and seeing what the author saw when he glanced up from his tablet. Alice Freeman’s words reverberate—there’s a point out from his house—his writing shack, she meant, where the salt-stained window reveals Margaree island shining in the sun, and just north of the shack a point of land facing the sea as if rushing out to meet it.Macleod brought these coastal cliffs and harbors, country lanes and isolated cottages to life in New York, London, Tokyo, wherever No Great Mischief is being read. Yes, I know, the fictional Calum Ruadh Point was a creation of the author’s fertile imagination, but until someone sends me in a different direction, given the view from the writer’s shack, this fictional landmark of Alistair MacLeod’s Cape Breton Island belongs to me.

Larry Wells is the author of two historical novels (Doubleday & Co) and has edited six non-fiction books. He was awarded the 2014 Faulkner-Wisdom prize for narrative non-fiction at the Words and Music Festival, New Orleans.

Debbie Crenshaw

November 15, 2017 at 2:11 pm

In his continued tradition, Larry Wells transports us to Cape Breton and the works of Alistair MacLeod. Beautiful landscape and azure coast paint the Breton scenery. Thanks, Larry, for sharing all this with us. From one of your former students, Debbie Crenshaw