Arts & Entertainment

Review: Chernow’s “Grant” Is a “Masterful and Readable” Portrait of an Admirable Leader

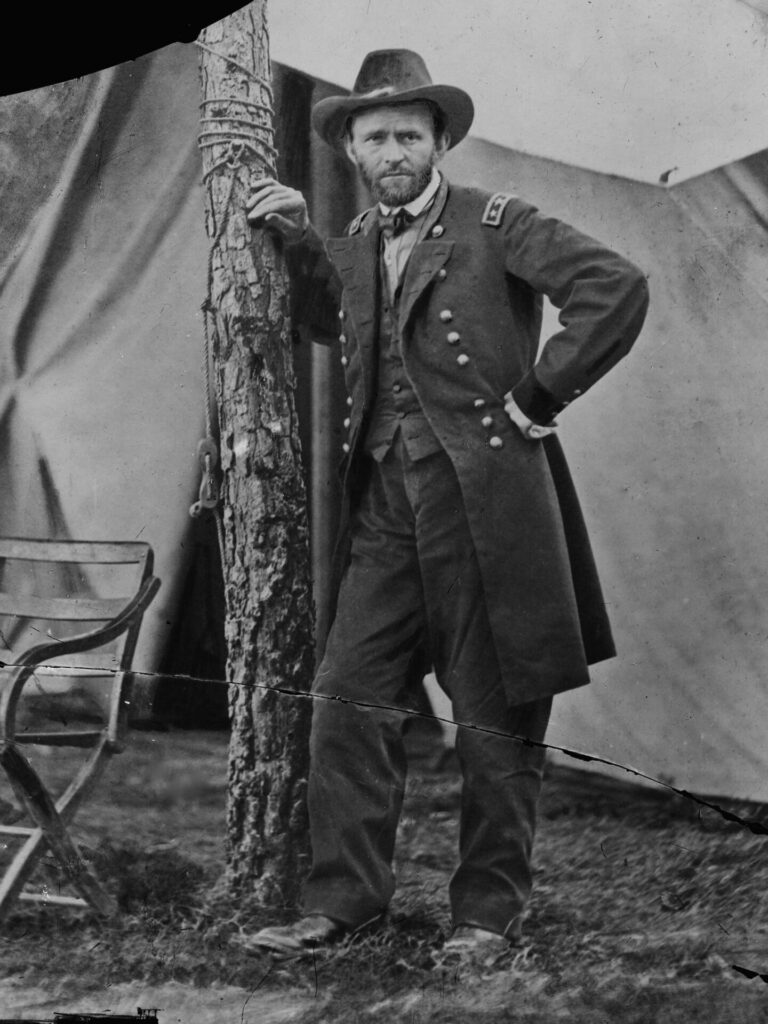

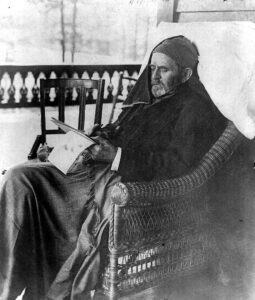

Ulysses S. Grant in 1864, commanding the Army of the Potomac. Photo Credit: Matthew Brady.

Grant, by Ron Chernow. Penguin Press, 1,074 pages, $40.

A horseman who rode superbly and drove his buggy like a demon. A loving family man. A hard-working, easy-going farmer. An alcoholic with no head for business. Of all American generals, the best at handling setbacks (“not a retreating man,” as Robert E. Lee warned). An American everyman and a president who told jokes on himself. A writer who mastered his craft as he lay dying. In this admirable biography of Ulysses S. Grant—a book that is solid in every sense, long and fact-packed, masterful and readable—Ron Chernow sketches these profiles, and more, of the man whose worn but resolute face looks out from the fifty-dollar bill.

A horseman who rode superbly and drove his buggy like a demon. A loving family man. A hard-working, easy-going farmer. An alcoholic with no head for business. Of all American generals, the best at handling setbacks (“not a retreating man,” as Robert E. Lee warned). An American everyman and a president who told jokes on himself. A writer who mastered his craft as he lay dying. In this admirable biography of Ulysses S. Grant—a book that is solid in every sense, long and fact-packed, masterful and readable—Ron Chernow sketches these profiles, and more, of the man whose worn but resolute face looks out from the fifty-dollar bill.Alcoholism shadows this book, as it shadowed Grant’s early career. Grant started drinking as a young lieutenant, after the Mexican War. He could not touch alcohol without becoming completely, convivially, helplessly drunk. In 1854, after two lonely years in forts on the West Coast, far from his family, alcoholism gripped him, and it cost him his commission.

Soldiers from the 47th Illinois Infantry Regiment pose for a photographer in Oxford during the first phase of Grant’s Vicksburg campaign in December 1882.

In 1861, when Lincoln called for volunteers, Grant re-entered the army as the colonel of an Illinois regiment. The Civil War offered Grant a second chance. For Grant did not drink all the time, and his self-control, although not absolute, could be iron-clad. He did not drink when he was with his wife. He did not drink at army banquets. He never let his men see him drunk. He did not drink, Chernow writes, “during combat periods, when he was actively engaged and shouldered responsibility” (his chief of staff, John Rawlins, served as Grant’s “resident conscience” and was tasked with keeping his commander sober).

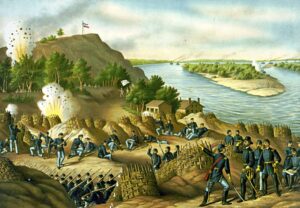

The Siege of Vicksburg, as imagined by lithographers after the war. At lower right, General Grant studies the Confederate lines. Credit: Chromolithograph by Kurz & Allison

Grant won victories that freed Kentucky and Tennessee, opened the Mississippi River by capturing Vicksburg, and was brought east to deal with Robert E. Lee. In May 1864, he fought Lee in the Battle of the Wilderness and suffered heavy losses. Previous Union commanders had used such losses as an excuse to break off fighting. Grant, instead, drove on; he meant to fight until the war came to a close. He kept moving, forcing a battle at every river and crossroads, fighting almost daily. When he could not reach Richmond from the north, he slipped loose and marched and threatened it from the south. Within eight weeks Grant had done what no Union commander had been able to do in three years: immobilize Robert E. Lee. He forced Lee’s army to entrench itself at Petersburg, besieged it there for nine months, and finally trapped it when it tried to escape.

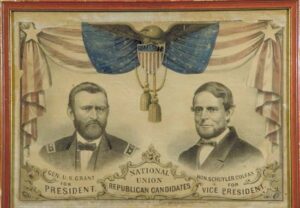

After the war, Chernow shows, Grant played a central role in Reconstruction. As general of the army, perhaps the most popular man in Washington, he sided with Congress and the Radical Republicans, but he may have dissuaded them from arresting Andrew Johnson while impeachment was pending. Elected president in 1868—thousands of new black voters helped carry the South for him—he ended his inaugural address by calling for ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, guaranteeing all citizens’ right to vote. He signed the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, using federal troops to break the Klan.

This Republican campaign poster from 1868 features Grant and his running mate, Schuyler Colfax.

Grant’s second term was heavier going. In 1873, a business panic brought years of depression. The Whiskey Ring scandal, a matter of tax fraud and corrupt treasury agents, involved Grant’s longtime personal secretary. A scandal over Indian agencies involved Grant’s brother (and became linked to a legendary military disaster, the Sioux massacre of George Armstrong Custer and his command). After hesitating to send troops south to support embattled Republican governors, Grant saw his administration end with the contested election of 1876 and the collapse of Reconstruction.

One last debacle remained. Grant allowed his money and reputation to be used by a promising young financier, Ferdinand Ward. The brokerage firm of Grant & Ward had its offices at 2 Wall Street; Grant arrived every weekday morning at ten o’clock, but never asked exactly how the firm made money, checked its books, or hesitated to sign letters that Ward handed him. As Charles Ponzi would later do, Ward paid out early investors with money paid in by later investors. In another pattern of fraud, Ward used the same collateral (deposited securities) to secure several different loans. He also hinted to investors that Grant’s behind-the-scenes influence had won him government contracts.

Ward’s scheme collapsed in May 1884. Grant was ruined: he had invested his life savings with Ward, and whatever he had left, as a general partner in the firm, he owed to its creditors. He left the offices without speaking to reporters. In June, Grant felt a stinging pain in his throat while eating a peach; he thought he had swallowed a wasp, but by October he knew it was cancer. He had earlier resolved not to write his memoirs. He changed his mind and signed a contract with Mark Twain that guaranteed him 70% of the net profits.

The biographer of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, J.P. Morgan, and John D. Rockefeller, Chernow knows first-hand the hard work Grant was doing.

Dying of throat cancer, Grant wrote his memoirs. He produced a book of 366,000 words in a year’s time. Photo Credit: Library of Congress.

“Grant toiled four to six hours a day, adding more time on sleepless nights. For family and friends, his obsessive labor was wondrous to behold: the soldier so famously reticent that someone quipped he ‘could be silent in several languages’ pumped out 336,000 words of superb prose in a year … [Twain] was agog when Grant dictated at one sitting a nine-thousand-word portrait of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, ‘never pausing, never hesitating for a word, never repeating—and in the written-out copy he made hardly a correction.’”

The general finished “The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant” scant days before he died. With their lapidary style, common sense and generosity, his autobiography gave Americans reason to once more honor their author. With this book, Chernow has realized a similar success, a masterpiece of sweeping narrative and sharp detail. “Grant” has earned a place on the same shelf as the Memoirs.

Allen Boyer, the Book Editor for HottyToddy, formerly worked three doors down from 2 Wall Street. His book “Rocky Boyer’s War,” a WWII history based on his father’s wartime diary, was recently published by the Naval Institute Press.