Featured

Unconquered and Unconquerable: The Puzzle Of The Natchez Indians

NATCHEZ — Mounds. Medicine men. Child sacrifice. The Tattooed Serpent. The Great Sun.

Mississippi’s Natchez Indians were nothing, if not exotic.Unfortunately, much of the recorded history of the tribe is just as mysterious as all that’s missing. What is known comes from written accounts of the French and English who encountered them in the 1600s and 1700s. According to historian Jim Barnett, author of Mississippi’s American Indians, “these records don’t give us a complete picture of the Natchez Indians, but do provide us with a glimpse of a living tribe.”

One of the mounds still preserved at the Grand Village of the Natchez

Indians, located right next to a modern-day subdivision

Other intriguing tidbits have surfaced from the earth, as archaeologists have probed for clues at the site of the Grand Village of the Natchez, surrounded today by the modern city of Natchez, known more for its immaculately preserved antebellum mansions. Unfortunately, much of the tribe’s history has been lost forever. The pieces that are left from an unfinished puzzle.

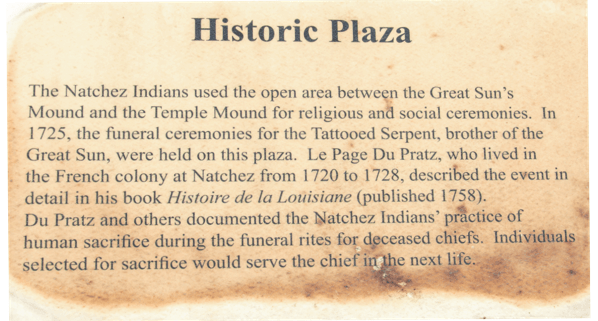

Where did they come from? Why was their culture so unique compared to other tribes? Complete answers may never come. A good bit of what is known is on display at a small museum at the village site itself. Located inside the city limits, it’s less than five miles from the Mississippi River, with Saint Catherine’s Creek on one side and a typical American subdivision on the other. A small museum offers a look at artifacts carefully pried from the soil by archaeologists. Historical plaques explain the significance of the site and some of the Natchez customs.

Three mounds stand in a straight line separated by 100 yards of flat land, once plazas for the tribe. Archaeologists excavated two of the three and found they were built in as many as four different stages, raising the flat platform top more each time.

The Indians’ process of mound building opens a small window into Natchez life. It took a long time to build these mounds. Natchez people collected basket loads of dirt, poured them on top, and started again. The mounds signify a devotion to religion along with a comfortable lifestyle, with plenty of time for both. On one of these mounds resided the Great Sun, the Natchez chief.

The chief and his relatives lived elevated over those of lower status. Tribal organization was based upon matrilineal kinship. One’s standing within the two rankings of nobility and commoner was inherited from the mother. The highest of the nobles, the “Suns,” were the Natchez royal family. While the Great Sun inherited his office from his mother, the royal line would further continue through the chief’s oldest sister.

Archaeologists found evidence that another excavated mound was the Temple Mound, a site of Natchez religious practices. Just as the early written accounts of Frenchmen had indicated, the mound bore a structure with architecture that was distinct from other Natchez dwellings. On its roof were two bird figures, and inside a flame was always ablaze.

At this same structure, Antoine Simon Le Page du Pratz witnessed the funeral of the Tattooed Serpent in 1725. A Dutchman operating a cotton plantation in Natchez, du Pratz was enamored by the natives’ culture, and this particular ceremony was to be a distinguishing event.

The Tattooed Serpent was a man he had known: the brother of the Great Sun

and the tribe’s negotiator in times of trouble with the French.

Because of the many noble deeds done in the Tattooed Serpent’s lifetime, tribal members commemorated his death with perhaps the greatest of deeds.

Barnett wrote that “Du Pratz witnessed the elaborate funeral ceremony and described the voluntary sacrifice of the deceased man’s wife and members of his entourage by strangulation with bowstrings.”

Sacrificial victims felt the duty to continue serving the Tattooed Serpent in the afterlife and felt it dishonorable for him to arrive there alone. Furthermore, the Natchez killed their own babies to commemorate the lives of members of the Sun family, throwing infants to be stomped on as funeral processions marched by.

Just as cringe-worthy is the Natchez practice of primitive tattoos. Sometimes covering one’s whole body, artistic designs were made permanent by cutting open the skin. A colored substance, such as black ash, was added to the wound. As it began to heal, the skin was cut open again, and the process was repeated, with no concern for the possibility of death by infection.

But perhaps the Natchez escaped the fate of infection with their health practices and mysterious medicine men. Du Pratz wrote of two suffering Frenchmen and how one was fully cured by Natchez practitioners:

“I have seen [the native doctors] perform surprising cures on Frenchmen; on two especially, who had put themselves under the hands of a French surgeon settled at [the Natchez] post. After having been under the hands of the surgeon for some time, their heads swelled to such a degree, that one of them made his escape, with as much agility as a criminal from the hands of justice. He applied to a Natchez Indian physician, who cured him in eight days. His comrade continuing still under the French surgeon, died under his hands three days after the escape of his companion, whom I saw three years after in a state of perfect health.”

The French and the Natchez first met on March 26, 1682, when the LaSalle expedition penetrated the area. That connection would continue over the course of the next 48 years. The French foothold in the Southeast established by Iberville and communication down the Mississippi River were eventually secured with a military outpost in the town of Natchez.

In the early 1700s, the French maintained peaceful relations with Natchez natives, trading with each other and doing their best to communicate. A fort was established. In time, there were misunderstandings due to language. And each side felt superior to the other. Inevitably, tensions arose.

In the 1720s, disputes over debts and land led to conflict and the capturing of Natchez women by the French. Attempts by the English to sway the tribe away from its alliance with the French led to more bad blood.

The Tattooed Serpent and the Great Sun had been influential in suppressing the rising pro-English feelings within the tribe. But following their deaths in the late 1720s, tribal resentment toward the French rose unabated.

On the morning of Nov. 28, 1728, the Natchez attacked the unsuspecting colonials and killed between 200 and 300 Frenchmen. Retaliation by the French led to two years of intermittent and bloody fighting that finally came to an end in 1731. The Natchez were eventually forced to surrender to French forces led by Gov. Etienne Périer. The captives were sent to New Orleans.

But some Natchez escaped before the surrender, and moved north, seeking protection with the English-allied Chickasaws. Over the years, Natchez Indians would continue to move further east and eventually join Creeks and Cherokees, dispersing the remnants of their tribe across the Southeast and losing any real semblance of tribal organization.

Today, a small remnant of the tribe has a website and an organization but so far they have failed to win recognition from the federal government. But the trials and near-annihilation of the Natchez Indians has left an indelible historical footprint in Mississippi, a cultural imprint that also raises questions that may never be answered.

Most evident, though, are the mounds still standing at the tribe’s home base. Today, nearly 300 years later, people can hike to their tops and look over the same plaza that the Great Sun once admired from on high. In fact, atop one such mound, you can stand on potentially unwritten pieces of Natchez history.

In keeping with the mysteries of the tribe, archaeologists decided to leave one mound untouched. It has become the Natchez’s personal time capsule, unhindered by European settlement and unprobed by human hands. Maybe answers lie buried here, or maybe just more unanswered questions.

Some of the traditions of the Natchez Indians were outlined in this historical marker.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Ariel Cobbert, Mrudvi Bakshi, Taylor Bennett, Lana Ferguson, SECOND ROW: Tori Olker, Josie Slaughter, Kate Harris, Zoe McDonald, Anna McCollum,

THIRD ROW: Bill Rose, Chi Kalu, Slade Rand, Mitchell Dowden, Will Crockett. Not pictured: Tori Hosey PHOTO BY THOMAS GRANING

The Meek School faculty and students published “Unconquered and Unconquerable” online on August 19, 2016, to tell stories of the people and culture of the Chickasaw. The publication is the result of Bill Rose’s depth reporting class taught in the spring. Emily Bowen-Moore, Instructor of Media Design, designed the magazine.

“The reason we did this was because we discovered that many of them had no clue about the rich Indian history of Mississippi,” said Rose. “It was an eye-opening experience for the students. They found out a lot of stuff that Mississippians will be surprised about.”

Print copies are available October 2016.

For questions or comments, email us at hottytoddynews@gmail.com.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…