Featured

"For the Fifth Air Force – On Memorial Day"

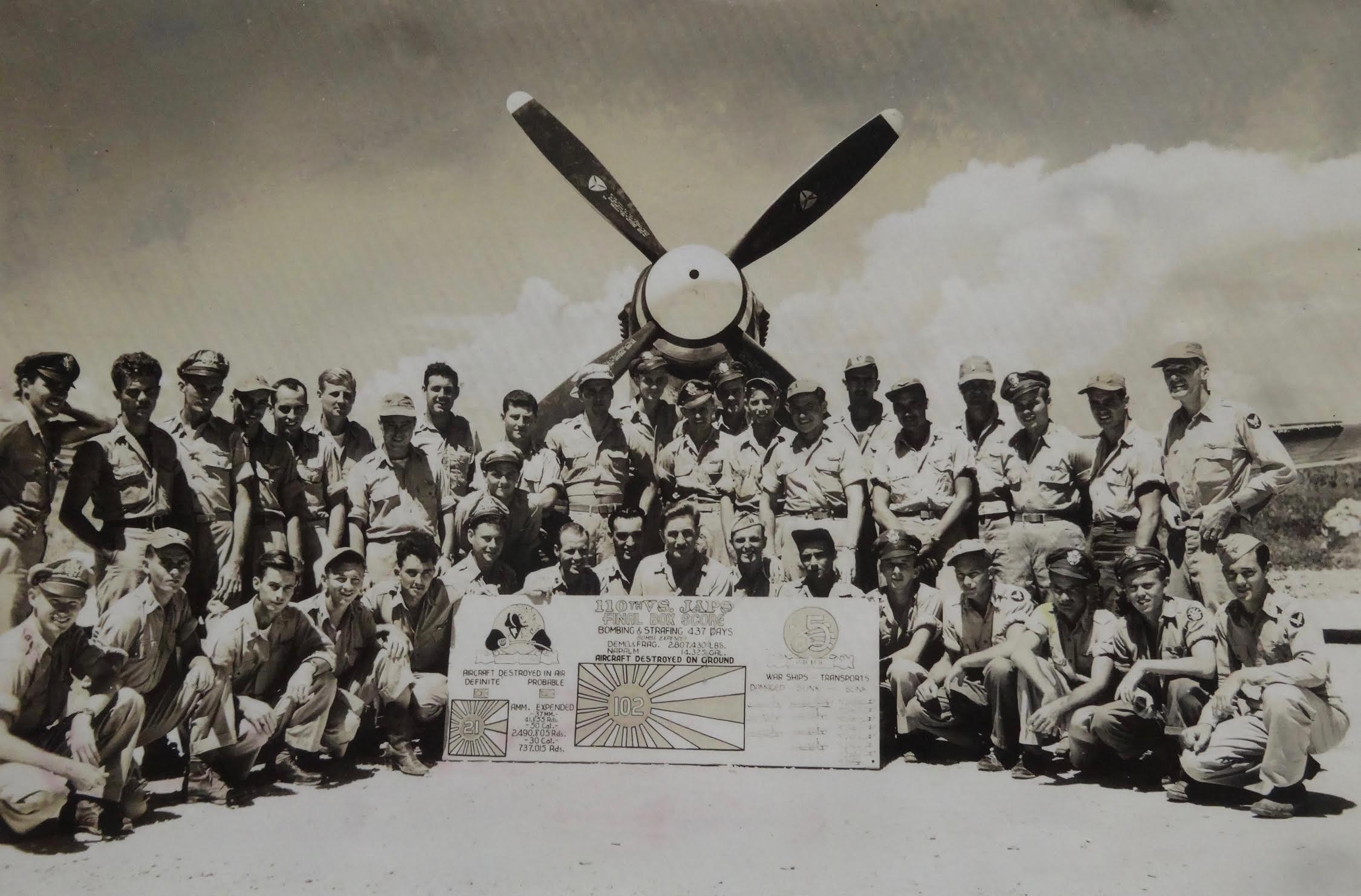

110th Squadron displays scorecard in front of Mustang to mark end of war

My father kept a diary during the Second World War. For three years now, writing a book based on it, I have been living with the Fifth Air Force. “The Forgotten Fifth,” it has been called: its bomber and fighter squadrons defended Australia and fought their way north to the Philippines, on the far side of the world, while Army publicity units filmed B-17’s bombing Germany and the Marines won fame for storming islands in the Pacific.

This Memorial Day, the Fifth Air Force deserves to be remembered. And as we honor the veterans who remain, we might honor them best by remembering them as what they were a crowd of young men, boisterous overall – some of them reckless, some of them careful, some of them heroes. Far from home, they defeated Japan.

In the Fifth Air Force, the gunners and mechanics were college-age, and the lieutenants and captains were barely older. Many colonels were still in their twenties. They found themselves in New Guinea, hundreds of miles from any city, setting up tents and digging privies. They stole each other’s Jeeps and scrounged Coca-Cola machines for their clubs. Some painted girlie pictures on their bombers. Some traded unit patches as if the Army were a branch of the Boy Scouts.

They were not saints. Lieutenant Bailey gypped my father and three other lieutenants when selling them a pint of what they thought was ice cream. Staff Sergeant Cahill in the combat camera section had a sideline in pornography. Corporal Dare in the motor pool became known as a smart-aleck – and as a satyr, when he went on leave to Australia. Things were fine there, he reported back, people accepted you as long as you stayed sober, and the women were okay too. On his last day of leave, down on the beach, he had met a girl and had sex with her four times in one afternoon. After the war, Dare went back to California, where he ran a paint and body shop. The women there were okay as well. The records show he was married at least three times.

They groused, continually. They all wanted to be promoted, and they all wanted to go home. Second Lieutenant Hartbard thought it unjust that he had not already made first lieutenant. Captain Seitz, the dentist, complained that the Army Medical Corps was run by doctors. Baptist chaplains complained that the Army Chaplain Corps was run by Roman Catholics. Lieutenants thought that their reconnaissance wing was top-heavy with colonels. Lieutenant Beck the Montana rancher thought that serving as WAC’s or nurses made women coarse; so did a group of sergeants whom my father overheard discussing “the post-war woman situation.”

Hard-drinking hard-living fighter pilots figure in war movies – but not all pilots lived hard or drank. In my father’s air group, Bertram Sill shot down two Japanese warplanes flying a bomber; his B-25 Mitchell nicknamed “Mitch the Witch”; he did it not by roaring into combat, but by banking and weaving to give his turret gunners clear shots at the enemy. On the ground, Sill was known as an ace at contract bridge. Verne Murphy was a slight, skinny pilot with black hair and a black mustache: he looked like Charlie Chaplin, or worse – Charlie Chaplin with a limp, and bad kidneys. He was, in fact, the best flyer in his squadron. Rubel Archuleta, who grew up on a homestead in New Mexico, was teaching school when the war started. When he took over as squadron commander, a different tone sounds in the squadron records. Under his command, the 110th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron started calling themselves The Flying Musketeers. Their new squadron blazon was a swordsman flexing his rapier (not the prewar cartoon of a goggle-wearing Missouri mule), and bombed convoys and fought it out with flocks of Zeros. Archuleta led the 110th across the Philippines and north to Okinawa.

The first man to face a court-martial was Lieutenant Zock. James Albert Zock was from Acadia Parish, in the Cajun rice country. Before the war, he was a football coach. He was a special services officer who specialized in running squadron softball teams. Zock showed bonhomie in other ways: he played blackjack well and found liquor for the officers’ club. When the group sent a B-25 on the first beer run to Australia, Zock took charge. Then a clerk noticed a code in Zock’s letters home. He had signaled to his family where he was based, by spelling out the location with the first letter of the first word in every paragraph. Fifth Air Force command recommended that Zock is court-martialed under the 104th Article of the Articles of War. This sounded ominous; in fact, it meant “company punishment,” the lightest sort of Army sanction – confinement to quarters, not the post stockade. Zock was soon back coaching softball.

Sometimes, from a few newspaper clippings, you can sketch the outline of a man’s story, and sense the costs of the war. Curtis Hancock was the pilot of a bomber shot down, by mistake. He was flying a mission to drop maps to troops on the beachhead; the American anti-aircraft gunners saw his plane coming in low, with its bomb-bay doors open, didn’t wait to check the markings, and shot the plane down. Captain Hancock was twenty-four when he died. He was a cheerful-looking young man, and he had more than 50 missions under his belt – enough to go home if he had been flying in other theaters of war. He left a wife in California, a mother in Texas, and a little daughter, sixteen months old. Four years later, Captain Hancock’s remains were brought home to Texas. The Lubbock newspapers mentioned his mother Addie and his daughter Nancy, both living nearby in Lamesa, and that his widow (not named) could be found in Florida.

The chaplains were very good. They preached on weekends, and during the week they took care of their flocks. They organized discussion groups and jazz bands. They set up holiday celebrations. The chaplains were the only officers who could keep the Colonels in line. When a flight surgeon kept a Red Cross girl in his tent overnight, or a group of colonels fired pistols and rolled dynamite downhill after midnight, to enliven a promotion party, it was the chaplains who called them to account. Chaplain Smith, new to New Guinea, had no hesitation in writing to General Douglas MacArthur.

Chaplain Smith – Captain Charles Frederick Smith, my father’s unit chaplain – was the hardest officer to trace. My father knew Chaplain Smith as a hard-working pastor, a very tall man who played the violin. You would think that a tall Baptist preacher who played the violin would attract attention – but that wasn’t so. His names were too common: even if an internet search turned up a minister named Charles F. Smith, you could not be sure it was the right man. The wartime Army chaplain school at Harvard had his military assignments; those records went up only to 1945. In 1956, a Reverend Charles Smith surprised his congregation by resigning as pastor of a large church in North Carolina. That might have been Chaplain Smith – this Reverend Smith was known as a scholar and had built a new sanctuary and had musical interests – but for two years, the trail went cold. Finally I found the right Chaplain Smith; it was the same man. When he resigned his pulpit, he went into teaching – that was what had shocked his church. He made a second career of it, as a teacher and principal and high-school counselor.

My father’s diary was an unvarnished history. He wrote of Chaplain Smith’s ministry and Lieutenant Zock’s contretemps and the other officers’ gripes – he was disgruntled himself. With the rest of the Fifth Air Force, he lived in tropical heat and downpours and coral dust – sometimes in combat with the Japanese, sometimes tied up in quartermasters’ snafus and headquarters politics. The airmen knew the ironies of the war. They earned their honors, their decorations and the title of the Greatest Generation, in a war for which they were drafted, in battles that their nation too often overlooked. The greater irony and their achievement was that even though it was not the war they would have chosen, they showed the strength to win it.

Allen Boyer, Book Editor for HottyToddy, is a native of Oxford. He lives and writes on Staten Island. His new book “Rocky Boyer’s War: An Unvarnished History of the Air Blitz That Won the War in the Southwest Pacific,” a WWII history drawing on his father’s diary, has been published by the Naval Institute Press.

Follow HottyToddy.com on Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat @hottytoddynews. Like its Facebook page: If You Love Oxford and Ole Miss…